Barry Lituchy is a history professor at Kingsborough Community College.

Month: April 2020

Aldabra Atoll

The atoll is comprised of four large coral islands which enclose a shallow lagoon; the group of islands is itself surrounded by a coral reef. Due to difficulties of access and the atoll’s isolation, Aldabra has been protected from human influence and thus retains some 152,000 giant tortoises, the world’s largest population of this reptile.

Brief synthesis

Located in the Indian Ocean, the Aldabra Atoll is an outstanding example of a raised coral atoll. Due to its remoteness and inaccessibility, the atoll has remained largely untouched by humans for the majority of its existence. Aldabra is one of the largest atolls in the world, and contains one of the most important natural habitats for studying evolutionary and ecological processes. It is home to the largest giant tortoise population in the world. The richness and diversity of the ocean and landscapes result in an array of colours and formations that contribute to the atoll’s scenic and aesthetic appeal.

Criterion (vii): Aldabra Atoll consists of four main islands of coral limestone separated by narrow passes and enclosing a large shallow lagoon, providing a superlative spectacle of natural phenomena. The lagoon contains many smaller islands and the entire atoll is surrounded by an outer fringing reef. Geomorphologic processes have produced a rugged topography, which supports a variety of habitats with a relatively rich biota for an oceanic island and a high degree of endemism. Marine habitats range from coral reefs to seagrass beds and mangrove mudflats with minimal human impact.

Criterion (ix): The property is an outstanding example of an oceanic island ecosystem in which evolutionary processes are active within a rich biota. Most of the land surface comprises ancient coral reef (~125,000 years old) which has been repeatedly raised above sea level. The size and morphological diversity of the atoll has permitted the development of a variety of discrete insular communities with a high incidence of endemicity among the constituent species. The top of the terrestrial food chain is, unusually, occupied by an herbivore: the giant tortoise. The tortoises feed on grasses and shrubbery, including plants which have evolved in response to its grazing patterns. The atoll’s isolation has also allowed the evolution of endemic flora and fauna. Due to minimal human interference, these ecological processes can be clearly observed in their full complexity.

Criterion (x): Aldabra provides an outstanding natural laboratory for scientific research and discovery. The atoll constitutes a refuge for over 400 endemic species and subspecies (including vertebrates, invertebrates and plants). These include a population of over 100,000 Aldabra Giant Tortoise. The tortoises are the last survivors of a life form once found on other Indian Ocean islands and Aldabra is now their only remaining habitat. The tortoise population is the largest in the world and is entirely self-sustaining: all the elements of its intricate interrelationship with the natural environment are evident. There are also globally important breeding populations of endangered green turtles, and critically endangered hawksbill turtles are also present. The property is a significant natural habitat for birds, with two recorded endemic species (Aldabra Brush Warbler and Aldabra Drongo), and another eleven birds which have distinct subspecies, amongst which is the White-throated Rail, the last remaining flightless bird of the Western Indian Ocean. There are vast waterbird colonies including the second largest frigatebird colonies in the world and one of the world’s only two oceanic flamingo populations. The pristine fringing reef system and coral habitat are in excellent health and distinguished by their intactness and the sheer abundance and size of species contained within them.

Integrity

The property includes the four main islands which form the atoll plus numerous islets and the surrounding marine area. It is sufficiently large to support all ongoing biological and ecological processes essential for ensuring continued evolution in the atoll. The remoteness and inaccessibility of the atoll limit extensive human interference which could otherwise jeopardize ongoing processes. As such, Aldabra displays an almost intact ecosystem, sustaining naturally viable populations of all key species.

Protection and management requirements

The property is legally protected under national legislation and is managed by a public trust, the Seychelles Islands Foundation, with daily operations guided by a management plan. Boundaries are ecologically viable but the extension of the seaward boundary some 20 km into the sea would provide additional protection to the marine fauna. While the remoteness of the property has limited human interference, thus contributing for the protection of the biological and ecological processes, it also poses tremendous logistical challenges. Tourism is limited and carefully controlled. Whilst the property displays an almost intact ecosystem, protection and management need to address the constant threats posed by invasive alien species, climate change and oil spills, particularly in the event that oil exploration increases in the wider region.

President George Bush Busts a Move & Plays Drums

Former President Bush danced with members of Kankouran West African Dance Company during a Rose Garden event to mark Malaria Awareness Day at the White House, April 25, 2007.

Back to the Future | Reelviews Movie Reviews

Had Back to the Future come to life as originally envisioned by the purse string-holders at Universal Pictures (which owned the rights to Bob Gale’s screenplay), it might have been a very different project, with Eric Stoltz in the lead role. Stoltz, however, bowed out early during filming due to that ever-popular reason: “creative differences,” opening the door for Michael J. Fox (or, as nearly everyone knew him at the time, Alex P. Keaton). Would Back to the Future have become a modern classic with a different lead actor? That’s as much of an unknown as what Casablanca would have been like with Ronald Reagan asking Sam to play “As Time Goes By.” What is known, however, is that the version of Back to the Future produced by Robert Zemeckis remains one of the mid-’80s most enduring and enjoyable confections: an infectious mix of comedy, fantasy, satire, excitement, and nostalgia.

In 1985, Marty McFly (Fox) is an average high school teenager with a pretty girlfriend and a lousy home life. His father, George (Crispin Glover), is a spineless toady who can’t so “no” to his overbearing boss, Biff Tannen (Thomas F. Wilson), and his mother, Lorraine (Lea Thompson), is a nagger. Marty spends as much time away from home as possible, often stopping by the house of Doc Brown (Christopher Lloyd), the local mad inventor. But Doc Brown’s latest invention – in function if not appearance – is anything but laughable. It’s a DeLorean converted into a time machine. When Marty inadvertently ends up in the driver’s seat, he is sent back 30 years to 1955. His appearance in an era before he was born forces him to seek out a younger version of Doc Brown, but also has unintended consequences. When a teenage Lorraine become infatuated with him, she loses all interest in other boys and this puts the future, and Marty’s existence, in jeopardy.

Back to the Future is played neither entirely seriously nor entirely for laughs, and therein lies the nature of its success. It’s funny and breezy but doesn’t descend to a level where the characters are little more than props for jokes. We believe in Marty, like him, and root for him to succeed. Part of the reason for that is Michael J. Fox, whose unforced screen charisma had already made him a huge television success. (He was the #1 reason Family Ties was a Sunday night staple.) Fox brought a lion’s share of that “aw shucks” affability to Marty, and Back to the Future launched Fox’s big-screen career. In order to appear in Back to the Future (once he had agreed to replace Stoltz), Fox had to go virtually without sleep. During the day on weekdays, he would film Family Ties episodes. At nights and on weekends, he made Back to the Future.

Like Crocodile Dundee one year later, Back to the Future is at its heart a “fish out of water” story, about an ’80s boy being trapped in a 1950s small town. His mother is smitten with him, the local bully doesn’t like him, his dad is a wimp, and he doesn’t fully understand the customs and lingo of the period in which he has become stranded. Plus, there are the twin difficulties of repairing a state-of-the-art 1980s time machine using 1950s technology and patching the damage his presence has caused to the time continuum. Zemeckis plays much of this with a light touch, but when there are opportunities for some excitement (as when Marty has a deadline to get to the “finish line” or risk not getting to 1986 until he’s middle-aged), he milks it for all it’s worth. Back to the Future leaves viewers a little breathless, but not drained – exhilarated and smiling.

Nostalgia plays a role in Back to the Future’s success. For kids in the ’80s, it suggested the ’50s of Leave it to Beaver and other black-and-white sit-coms that were in UHF re-runs around the time Back to the Future opened. For 40-somethings, the movie provided a glimpse of their past through rose-colored glasses (always the best way to remember high school). When the film is watched today, some 25 years after its release, the nostalgia is double-barreled. Now, the ’80s scenes are as evocative as the ’50s material.

Back to the Future represented a career resuscitation for Christopher Lloyd, whose popularity had nosedived after the cancelation of Taxi, where he spent six years playing Reverend Jim. Roles in Star Trek III: The Search for Spock and Buckaroo Banzai enabled him to avoid obscurity, but it was his wacky turn as Doc Brown that defined his movie career. He plays the Doc like a stereotypical mad scientist – as brilliant as he is forgetful, a combination of Einstein and Doctor Who. Lea Thompson, a popular choice of the era to play high school sweethearts (see also All the Right Moves and Some Kind of Wonderful), shows that Lorraine is less prim-and-proper than her middle-aged self might indicate. (How many of us, I wonder, would be surprised if given an opportunity to interact with our parents when they were teenagers?) Crispin Glover, who has always marched to his own beat (as in his infamous appearance on David Letterman’s talkshow in 1987), is wonderful as the quavering, self-doubting George. For Glover, this may have been the most mainstream role he ever accepted (and he quickly distanced himself from it after the movie was released). Thomas F. Wilson provides a deliciously cartoonish sense of menace in his portrayal of the film’s thuggish villain, Biff.

If there’s a problem with Back to the Future, it’s the film’s ending, which left open the expectation that there would be more chapters to come. In fact, the movie was originally designed as a one-off project, with the final scene being a quirky way to wrap up things rather than a teaser for another installment. However, when Back to the Future topped the 1985 box office and public sentiment was high in wanting to know what the problem was with Marty and Jennifer’s kids, Zemeckis went to work on Back to the Future Part II and III, which were filmed back-to-back and took four years to reach the screen. In retrospect, it might have been better if they had died in development. Rarely have sequels underwhelmed to this degree, with Part II seeming forced and awkward and Part III tired and unnecessary. As a movie, Back to the Future is tremendous fun, but the series is memorable only for what started it.

The ’80s were a dark and cynical decade, remembered by most for excesses of consumption and greed. Back to the Future is unapologetically lighthearted and upbeat – a tonic for a weary movie-going society. Even its theme song (Huey Lewis’ “The Power of Love”) brought a smile to the face on its way up the charts to the #1 position. For Zemeckis, this represented an opportunity to join his buddy Steven Spielberg on the A-list – his next film would be Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, and Forrest Gump was less than a decade away. Like Spielberg, Zemeckis has a keen understanding of how to blend diverse elements of comedy, action, adventure, and drama into concoctions that win over audiences. Marty’s story could easily have been suspenseful, purely comedic, or a three-hankie melodrama, but Zemeckis found the balance and employed it. Back to the Future is a success because of a compelling premise, terrific casting, and exemplary execution. It’s the kind of alchemy that, on those rare occasions when it materializes, cannot be replicated – as the filmmakers discovered when they re-assembled for Back to the Future Part II. The magic lasted for one film, and that’s the one to re-visit.

Just finished watching Godzilla vs. Biollante (1989) and Zombie High (1987)…

Igor Nazaruk – All Costs Paid (Main Theme)

Main theme from the 1988 Soviet film All Costs Paid. Composed by Igor Nazaruk.

All Costs Paid (За всё заплачено) is a three-part television feature film from 1988, filmed by director Alexei Saltykov and based on the documentary novel of the same name by A. Smirnov. It’s one of the first films to show the war of the USSR in Afghanistan.

1453: The Fall of Constantinople

The city of Constantinople (modern Istanbul) was founded by Roman emperor Constantine I in 324 CE and it acted as the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, or Byzantine Empire as it has later become known, for well over 1,000 years. Although the city suffered many attacks, prolonged sieges, internal rebellions, and even a period of occupation in the 13th century CE by the Fourth Crusaders, its legendary defences were the most formidable in both the ancient and medieval worlds. It could not, though, resist the mighty cannons of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, and Constantinople, jewel and bastion of Christendom, was conquered, smashed, and looted on Tuesday, 29 May 1453 CE.

An Impregnable Fortress

Constantinople had withstood many sieges and attacks over the centuries, notably by the Arabs between 674 and 678 CE and again between 717 and 718 CE. The great Bulgar Khans Krum (r. 802-814 CE) and Symeon (r. 893-927 CE) both attempted to attack the Byzantine capital, as did the Rus (descendants of Vikings based around Kiev) in 860 CE, 941 CE, and 1043 CE, but all failed. Another major siege was instigated by the usurper Thomas the Slav between 821 and 823 CE. All of these attacks were unsuccessful thanks to the city’s location by the sea, its naval fleet, and the secret weapon of Greek Fire (a highly inflammable liquid), and, most importantly of all, the protection of the massive Theodosian Walls.

The city’s celebrated walls were a triple row of fortifications built during the reign of Theodosius II (408-450 CE) which protected the land side of the peninsula occupied by the city. They extended across the peninsula from the shores of the Sea of Marmara to the Golden Horn, eventually being fully completed in 439 CE and stretching some 6.5 kilometres. Attackers first faced a 20-metre wide and 7-metre deep ditch which could be flooded with water fed from pipes when required. Behind that was an outer wall which had a patrol track to oversee the moat. Behind this was a second wall which had regular towers and an interior terrace so as to provide a firing platform to shoot down on any enemy forces attacking the moat and first wall. Then, behind that wall was a third, much more massive, inner wall. This final defence was almost 5 metres thick, 12 metres high, and presented to the enemy 96 projecting towers. Each tower was placed around 70 metres distant from another and reached a height of 20 metres. The towers, either square or octagonal in form, could hold up to three artillery machines. The towers were so placed on the middle wall so as not to block the firing possibilities from the towers of the inner wall. The distance between the outer ditch and inner wall was 60 metres while the height difference was 30 metres.

To take Constantinople, an army would, then, need to attack by both land and sea, but all attempts failed no matter who tried and no matter what weapons and siege engines they launched at the city. In short, Constantinople, with the greatest defences in the medieval world, was impregnable. Well, not quite. After 800 years of resisting all comers, the city’s defences were finally breached by the knights of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 CE, although the attackers got in through a carelessly left-open door and not because the fortifications themselves had failed in their purpose. Repaired and rebuilt by Michael VIII (r. 1261-1282 CE) in 1260 CE, the city remained the most difficult military nut to crack in the world, but this reputation did not in any way deter the ever-more ambitious Ottomans.

The Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire had begun as a small Turkish emirate founded by Osman in Eskishehir (western Asia Minor) in the late 13th century CE, but by the early 14th century CE, it had already expanded into Thrace. With their capital at Adrianople, further captures included Thessaloniki and Serbia. In 1396 CE, at Nikopolis on the Danube, an Ottoman army defeated a Crusader army. Constantinople was the next target as Byzantium teetered on the brink of collapse and became no more than a vassal state within the Ottoman Empire. The city was attacked in 1394 CE and 1422 CE but still managed to resist. Another Crusader army was defeated in 1444 CE at Varna near the Black Sea coast. Then the new Sultan, Mehmed II (r. 1451-1481 CE), after extensive preparations such as building, extending, and occupying fortresses along the Bosporus, notably at Rumeli Hisar and Anadolu in 1452 CE, moved to finally sweep away the Byzantines and their capital.

The Defenders

The crushing of the Crusader army at Varna in 1444 CE meant that the Byzantines were now on their own. No significant help could be expected from the West where the Popes were already unimpressed with the Byzantine’s unwillingness to form a union of the Church and accept their supremacy. The Venetians did send a paltry two ships and 800 men in April 1453 CE, Genoa promised another ship, and even the Pope later promised five armed ships, but the Ottomans had by then already blockaded Constantinople. The people of the city could only stock up on food and arms and hope their defences would save them yet again. According to the 15th-century CE Greek historian and eyewitness Georges Sphrantzes, the defending army was composed of fewer than 5,000 men, not a sufficient number to adequately cover the length of the city’s walls, some 19 km in total. Worse still, the once great Byzantine navy now consisted of a mere 26 ships, and most of those belonged to the Italian colonists of the city. The Byzantines were hopelessly outnumbered in men, ships, and weapons.

It seemed that only divine intervention could save them now, but in the many previous sieges over centuries gone by, it was believed that just such intervention had saved the city; perhaps history would be repeated. Then again, there were also ominous tales of impending doom: prophesies that proclaimed the fall of Constantinople when the emperor was called Constantine (a good number were, of course) and there was an eclipse of the moon – which there was in the days before the siege of 1453 CE.

The Byzantine emperor at the time of the attack was Constantine XI (r. 1449-1453 CE), and he took personal charge of the defence along with such notable military figures as Loukas Notaras, the Kantakouzenos brothers, Nikephoros Palaiologos, and the Genoese siege expert Giovanni Giustiniani. The Byzantines had catapults and Greek Fire, the highly inflammable liquid which could be sprayed under pressure from ships or walls to torch an enemy, but the technology of warfare had moved on and the Theodosian Walls were about to get their sternest ever test.

The Attackers

Mehmed II had one thing that previous besiegers of Constantinople had lacked: cannons. And they were big ones. The Byzantines had actually had first option on the cannons as they had been offered them by their inventor, the Hungarian engineer named Urban, but Constantine could not meet his asking price. Urban then peddled his expertise to the Sultan, and Mehmed showed more interest and offered him four times what he was asking. These fearsome weapons were put to good use in November 1452 CE when a Venetian ship, disobeying a ban on traffic, was blown out of the water as it sailed down the Bosphorus. The captain of the vessel survived but was captured, decapitated, and then impaled on a stake. It was an ominous sign of things to come.

According to Georges Sphrantzes, the Ottoman army numbered 200,000 men, but modern historians prefer a more realistic figure of 60-80,000. When the army assembled at the city walls of Constantinople on 2 April 1453 CE, the Byzantines got their first glimpse of Mehmed’s cannons. The largest was 9 metres long with a gaping mouth one metre across. Already tested, it could fire a ball weighing 500 kilos over 1.5 km. So mammoth was this cannon that it took an awfully long time to load and cool it so that it could only be fired seven times a day. Still, the Ottomans had plenty of smaller cannon, each capable of firing over 100 times a day.

On 5 April, Mehmed sent a demand for immediate surrender to the Byzantine emperor but received no reply. On 6 April the attack began. The Theodosian Walls were relentlessly blasted, chunk by chunk, into rubble. The defenders could do no more than fire back with their own smaller cannons by day, hold off the attackers where the cannons had punched the biggest holes, and try and repair those gaps each night as best they could, using rocks, barrels, and anything else they could get their hands on. The resulting rubble piles actually absorbed the cannon shot better than fixed walls but, eventually, one of the infantry assaults would surely get through.

A Fight For Survival

The onslaught went on for six weeks but there was some effective resistance. The Ottoman attack on the boom which blocked the city’s harbour was repelled, as were several direct assaults on the Land Walls. On 20 April, miraculously, three Genoese ships sent by the Pope and a ship carrying vital grain sent by Alphonso of Aragon managed to break through the Ottoman naval blockade and reach the defenders. Mehmed, infuriated, then got around the harbour boom by building a railed road via which 70 of his ships, loaded onto carts pulled by oxen, could be launched into the waters of the Golden Horn. The Ottomans then built a pontoon and fixed cannons to it so that they could now attack any part of the city from the sea side, not just the land. The defenders now struggled to station men where they were needed, especially along the structurally weaker sea walls.

Time was running out for the city but, then, a reprieve came from an unexpected quarter. Back in Asia Minor, Mehmed faced several revolts as his subjects became unruly while their Sultan and his army were abroad. For this reason, Mehmed offered Constantine a deal: pay tribute and he would withdraw. The emperor refused, and Mehmed gave the news to his men that now, when the city fell, as surely it would, they could plunder whatever they wished from one of the richest cities in the world.

Mehmed launched a massive go-for-broke, throw-everything-at-them assault at dawn on 29 May. First to be sent in after the usual cannon barrage were the second-rate troops, then a second wave was launched with better-armed troops, and, finally, a third wave attacked the walls, this time composed of the Janissaries – the well-trained and highly determined elite of Mehmed’s army. It was during this third wave that disaster struck the Byzantines who by now were forced to employ women and children to defend the walls. Some fool had left the small Kerkoporta gate in the Land Walls open and the Janissaries did not hesitate in using it. They climbed to the top of the wall and raised the Ottoman flag, then they worked their way around to the main gate and allowed their comrades to flood into the city.

Destruction

Chaos now ensued with some of the defenders maintaining their discipline and meeting the enemy while others rushed back to their homes to defend their own families. It is at this point that Constantine was killed in the action, most likely near the Gate of St. Romanos, although, as he had discarded any indications of his status to avoid his body being used as a trophy, his demise is not known for certain. The emperor could have fled the city days before but he chose to stay with his people, and a legend soon grew up that he had not died at all but, instead, he had been magically encased in marble and buried beneath the city which he would, one day, return to rule again.

Meanwhile, the rape, pillage, and destruction began. Many of the city’s inhabitants committed suicide rather than be subject to the horrors of capture and slavery. Perhaps 4,000 were killed outright, and over 50,000 were shipped off as slaves. Many sought refuge in churches and barricaded themselves in, including inside the Hagia Sophia, but these were obvious targets for their treasures, and after they were looted for their gems and precious metals, the buildings and their priceless icons were smashed, the cowering captives butchered. Uncountable art treasures were lost, books were burned, and anything with a Christian message was hacked to pieces, including frescoes and mosaics.

In the afternoon, Mehmed entered the city himself, called an end to the pillaging and declared that the Hagia Sophia church be immediately converted into a mosque. It was a powerful statement that the city’s role as a bastion of Christianity for twelve centuries was now over. Mehmed then rounded up the most important survivors from the city’s nobility and executed them.

Aftermath

Constantinople was made the new Ottoman capital, the massive Golden Gate of the Theodosian Walls was made part of the castle treasury of Mehmed, while the Christian community was permitted to survive, guided by the bishop Gennadeios II. What was left of the old Byzantine empire was absorbed into Ottoman territory following the conquest of Mistra in 1460 CE and Trebizond in 1461 CE. Meanwhile, Mehmed, aged only 21 and now known as “the Conqueror”, settled in for a long reign and another 28 years as Sultan. Byzantine culture would survive, especially in the arts and architecture, but the fall of Constantinople was, nevertheless, a momentous episode of world history, the end of the old Roman Empire and the last surviving link between the medieval and ancient worlds. As the historian J. J. Norwich notes,

“That is why five and a half centuries later, throughout the Greek world, Tuesday is still believed to be the unluckiest day of the week; why the Turkish flag still depicts not a crescent but a waning moon, reminding us that the moon was in its last quarter when Constantinople finally fell.” (383)

Just finished watching A Thunder Of Drums (1961) and Spies In Disguise (2019)…

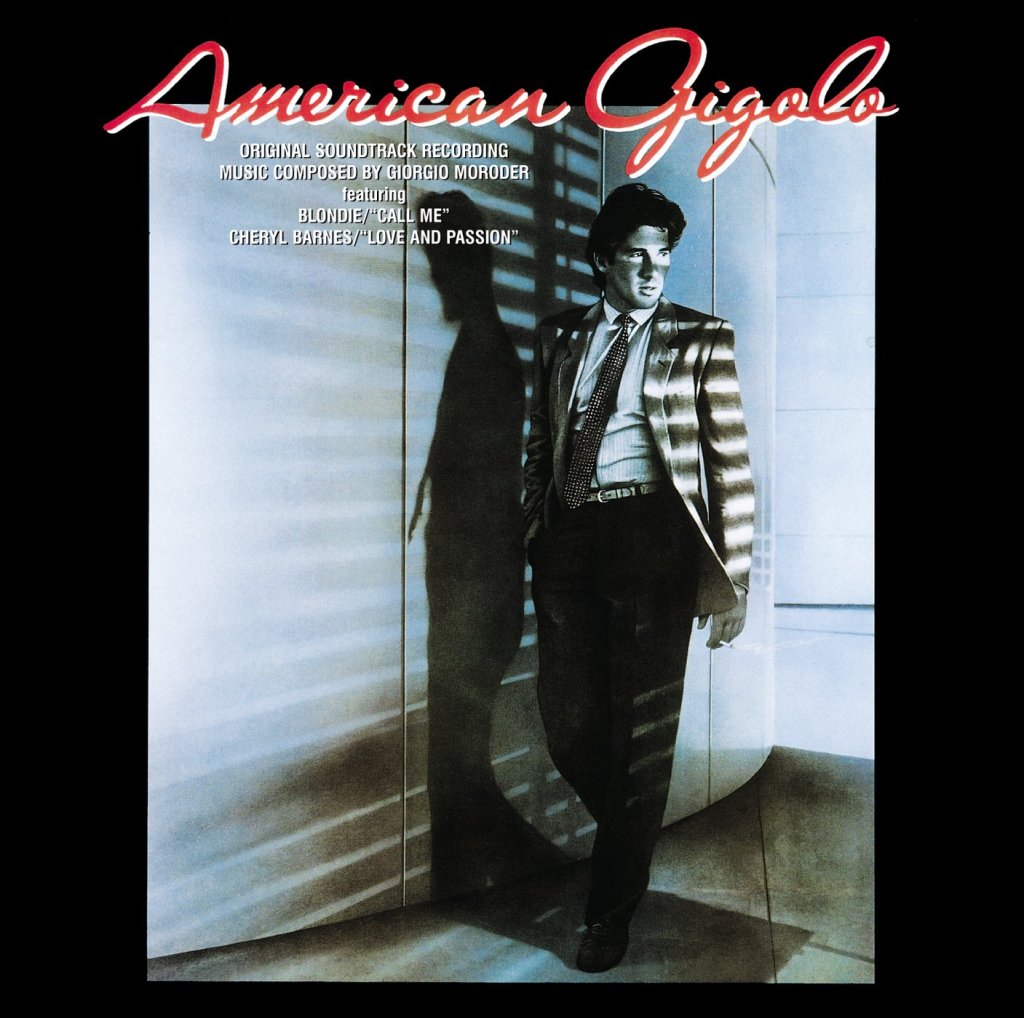

Now listening to Pyramid by The Alan Parsons Project and American Gigolo by various artists…