It is high time we stopped putting up with bullshit.

Nearly 7 years after the fact, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (N.I.S.T.), a division of the Commerce Department, finally released their report on the collapse of Building 7 today.

(pay careful attention to the sound on this. There are very few videos of the collapse of Building 7 with sound.)

We are told by N.I.S.T. that the cause of the buildings collapse was a standard “open” office fire caused a critical connection to fail due to what they call “heat expansion”, and that when that critical connection failed, it caused a domino effect with other connections, resulting in the perfectly symmetrical failure of the structure, starting with the center columns, resulting in the building falling and ending up in a perfectly neat pile, no bigger than it’s foundational foot-print. I don’t think so.

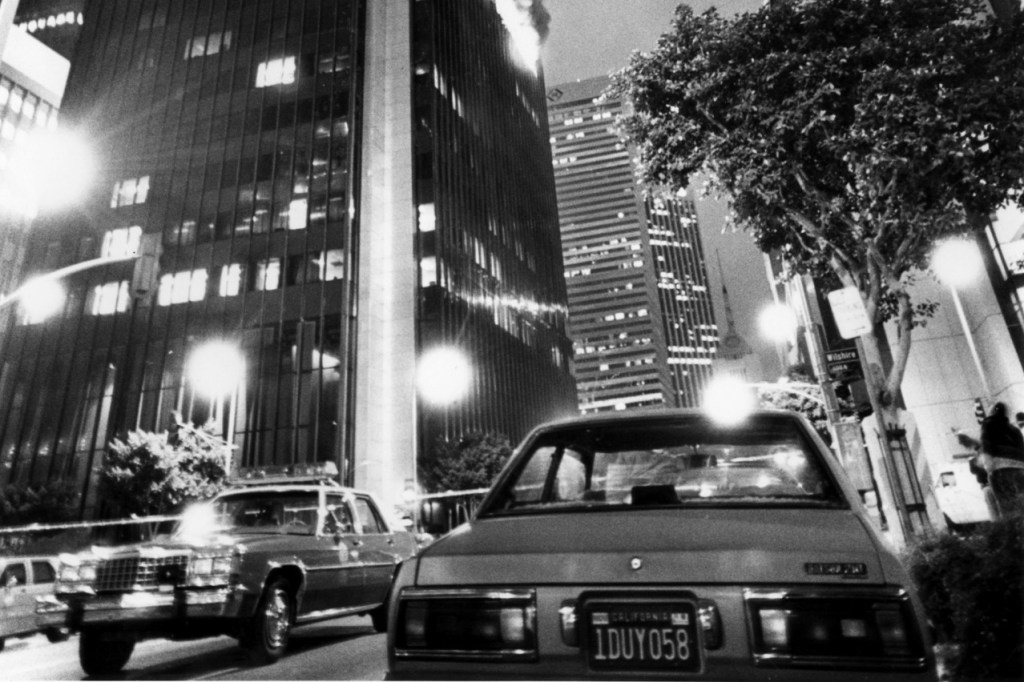

On May 5, 1988, The Interstate Bank building in L.A. burned for 3.5 hours and gutted 4 floors completely. It DID not collapse into a pile of rubble. Perhaps because for some reason, the “heat expansion” didn’t happen prior to 9/11.

On Feb. 13th 2005, in Madrid Spain, the Windsor building burned for over 15 hours at temperatures that reached over 1,400 F.

It burned so brightly that it illuminated Madrid all night. In the end, only a few floors failed on the upper level, and it still had enough structural integrity to support the massive construction crane that was on top of the building.

Nope. No “heat expansion” here.

The next day, this is what was left of the building. It took months to demo the building afterward, one piece at a time.

I wonder how much that costs? I bet Larry Silverstein knows.

This is the horrible inferno that was building 7. According to N.I.S.T.,

According to N.I.S.T., this is what destroyed building 7 of the WTC complex. Building 7 was newer and better designed than the previous 2 that I mentioned above. It was actually hand selected to be the home of the Office of Emergency Management because of it’s “bunker-like” design. Theoretically, this building was to be used in the event of a natural disaster in New York; like a massive earth-quake or a war of some kind. Yet, one little office fire caused it to end up like this;

Buildings 5 and 6 of the WTC complex stood between the North tower and Building 7. When WTC 1 (the North tower) collapsed, the debris cut Building 6 in half and severely damaged Building 5. The resulting fires burned for nearly 9 hours.

Yet, strangle enough, neither of these two buildings collapsed into their own foot-prints.

Building 5 burned out of control for nearly 9 hours; Building 6 was almost as bad.

So. I think it’s time we stopped letting our government agencies get away with lying to the American people about things that matter. Just a few weeks after the FBI released their make-believe story about Dr. Ivins being the anthrax killer, N.I.S.T. released this complete bullshit (not to mention, John McCain trying to tell us he doesn’t know how many houses he owns. I can believe he doesn’t know who the President of Russia is and whether or not Iran is training al Qaeda, but if there IS one thing this prick DOES know, it’s exactly how many houses he owns.)

I wouldn’t be surprised if we did attack Iran very soon. That will take people’s attention from nes like this, and make it harder for people like myself to question the “official story”, since, of course, we are supposed to “shut up” when we are at war.

N.I.S.T. knows this load of crap can’t hold up under the light of day for very long. Apparently, they had finished this report months ago, but for some reason, they withheld releasing it until now. With the naval build-up in the Gulf right now, it seems obvious to me that they were waiting for just the right time to release it, and then some other, bigger news story will drown this one out.