In the past two decades a concerted effort has been made by a group of compromised self-proclaimed historians like Rana Safvi and Ramachandra Guha to prove that everything good in India was brought to it by the Muslims and particularly the Mughals. One of the primary claims is that Mughal India was ‘rich’. Historian Saumya Dey in this brilliant article analyzes whether even this claim was true or not.

Those Pious, Grateful Liberals

It has been a while that I have been noticing a trend on social media. Every now and then, I see some pious liberal on Facebook or Twitter thanking the Mughals for making India ‘rich’. As the liberals imagine, Babur and his descendants made our country a veritable land of milk and honey. How tenable is this imagination though? And how right are our liberals in thanking the Mughals in retrospect?

We cannot deny that there was a lot of wealth in Mughal India, as is indicated by the grandeur of Mughal architecture. It sure cost a lot to construct the Red Forts at Agra and Delhi, the Taj Mahal, and the many tombs of the Mughal rulers and nobility. The Mughal dynasty and nobility possessed and flaunted a measure of wealth that inspired legends in contemporary Europe – Europeans talked about the ‘Great Mogul’s’ riches with awe. Indeed, in the English language we still sometimes refer to billionaire industrialists and bankers as ‘Moguls’. The sight of untold amounts of wealth reminds us of the Mughals even today. There is no doubt that the Mughal rulers and nobility lived it up.

However, was Mughal India truly and genuinely ‘rich’? Was there, in other words, general prosperity and economic wellbeing in Mughal India? By any means, just the ruler and the ruling class being wealthy does not make a country ‘rich’. One finds so many instances of Arab, African, or South American dictators amassing vast treasures and living lavishly. But these tyrants ruled desperately poor countries. So, I propose, we ought not to be blinded by the glittering affluence of the Mughal royalty and nobility and hastily term Mughal India ‘rich’. Let us first consider the living standards of the broad masses living in the Mughal realms. Only then, I believe, we shall be in a proper position to decide as to whether Mughal India was ‘rich’ or not.

The ‘Great Divergence’ and Impoverished Artisans

Mughal rule in India coincided with the onset of what many economic historians term the ‘Great Divergence’. What is meant by this is that living standards in Mughal ruled India began to noticeably fall behind those in Northwestern Europe. To put it in plainer language, as Mughal rule was first established and then consolidated over the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, most Indians seem to have beenquite worse off than the inhabitants of the relatively prosperous parts of Europe. This is indicated by some wage data provided in a research paper authored by Bishnupriya Gupta and Debin Ma. We see that average silver wages for unskilled workers amounted to 3.4 grams per day in southern Englandfrom 1550 to 1599. The comparable figure for India in the same period is only 0.7 grams. One must note that this is exactly the time when the Mughal Empire was striking roots in India. According to Gupta and Ma, the silver wage data “unambiguously” suggests that “the Great Divergence was already well established in the sixteenth century.” India, the two contend, now more resembled “the backward parts of Europe.” Again, the variance between silver wages in England and India remained considerable in the first half of the seventeenth century, when Mughal ‘glory’ was at its apogee. From the year 1600 to 1649, unskilled workers in the south of England earned 4.1 grams of silver wages per day on an average. Their Indian counterparts received only 1.1 grams of the same in this period.

Though I am unable to furnish wage data for skilled workers in Mughal India, it does not look like that they fared a lot better than their unskilled coevals. Going by anecdotal evidence, a lot of them appear to have provided their labor to the ruling class under coercion. In this sense, their situation seems comparable to that of the ‘dependent’ or ‘servile’ peasantry of feudal Europe. It was a common practice for the Mughal monarchs and nobility to have ateliers in their palaces and maintain a number of artisans. The French traveler Francois Bernier writes that “nothing but sheer necessity or blows from a cudgel” made them go on. As about the independent artisans, Bernier’s account suggests that they were quite inadequately compensated for what they made. For example, Bernier writes that the Mughal nobility were likely to “pay for a work of art considerably under its value and according to their own caprice….” An artisan, it seems, could not protest this treatment. If he did, he could suffer physical violence. According to Bernier, the Mughal ‘omrah’ [nobility] did not hesitate to “punish an importunate artist…with the korrah (sic.)”, or the whip. I assume, Bernier must mean “importunate” in demanding a fair price. I must also add that, having been personal physician to prince Dara Shikoh, Bernier must have had the opportunity to observe the ways of the Mughal nobility up close. Due to the princely patronage he enjoyed, he very possibly had access to Emperor Shahjahan’s court. It is, thus, very unlikely that our Frenchman is fibbing or making things up here.

Thus, poorly treated and paid by the rulers and nobility, artisans in Mughal India appear to have generally lived in poverty. As Bernier observes, they could aspire to nothing more than “satisfying the cravings of hunger” and dressing in the “coarsest raiment.” Upward mobility in this section of the population, it seems, was not common. Bernier’s verdict on the lot of the artisans is that they “could never hope to attain to any distinction” or purchase “either office or land….”

Agriculture in Mughal India

How did the great bulk of the Indian population, the peasantry, fare under Mughal rule? Not very well, as we see. A rich mine of information on agriculture, rural relations of production, and the peasantry in the Mughal Empire is Irfan Habib’s The Agrarian System of Mughal India. Currently Professor Emeritus at the Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University, this very detailed monograph by him throws considerable light on the sad plight of the peasantry in the Mughal Empire, its terrible oppression, and the ills that plagued the Mughal agrarian administration. Let me, by the way, point out to the reader that this is the same Irfan Habib who had charged at the Kerala Governor, Arif Mohammad Khan, at the Indian History Congress last year when he had spoken in support of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) during his speech. Prior to committing that act so richly becoming of his age and dignity, Prof. Irfan Habib had also, for years, used every possible ruse and casuistry to prevent the construction of a temple on the so called ‘disputed site’ at Ayodhya. Hence, I believe, when a man such as this concedes that agriculture and the peasantry in Mughal India were beset with a few problems, it must really have been so.

Irfan Habib writes that there was extensive trade in agricultural produce in the Mughal Empire.The nomadic banjaras, for example,transported foodgrains in bulk over long distances. These were then sold in marts in different corners of the Empire. This trade in foodgrains was also aided by the abolition of the many varieties of transit dues under Mughal rule. But did the peasantry benefit from this marketization of agricultural produce? No, not quite. There was, it seems, a considerable gap between the “price obtaining in the secondary market and that paid to the peasants.” As it seems, the latter price was much lower. This “margin” was probably caused by the peasants’ “indebtedness, the various cesses, the malpractices in the market and the imposition of monopolies….” The Mughal era Indian peasant, thus, does not appear to have been particularly prosperous, despite all the commercialization of agricultural produce that took place then. Therefore, we see that, while agricultural produce moved in the direction of the urban centers and was marketized, the opposite did not happen to a commensurate degree. Urban manufactures did not find a market in the rural areas, very likely because the peasants were in no position to purchase them. Habib writes that

“the more prosperous zamindars must have sought superior quality cloth, jewelry and weapons fashioned in the towns. But whether the peasants also contributed to such demand to any considerable extent may well be doubted. On the whole, the trade was heavily in one direction – from villages to towns.”

Discussing the living conditions of the general populace, Habib is remarkably candid. He quotes the Dutch traveler Palsaert who visited India in the reign of Jahangir. We see that Palsaert was particularly struck by the misery of the common masses. They, he observed, suffer from a poverty

“great and miserable…[and their life] can be depicted or accurately described only as the home of stark want and the dwelling place of bitter woe.”

Habib discusses the diet and clothing of the rural masses in the light of this remark. He admits that the peasants subsisted only on the coarsest grains. Sometimes, as a matter of fact, they could not afford even these. The peasants of Sind, for instance, writes Habib, survived on the seeds of a wild grass (called dair) “for quite a long period each year.” Just as the diet, the clothing of the rural people was extremely rudimentary, presumably on account of their wretched poverty. Vast numbers of rural men and women, it seems, could afford to cover only the middle of their bodies with a small piece of cloth. Habib mentions this Englishman who lived in India in Jahangir’s reign and observed that their forms would be naked but for “their privities (sic.).” Equally rudimentary and rude were the dwellings of the rural folks. These were fashioned out of bamboo, reeds, or mud.

Famines and periods of scarcity, one gathers from Habib’s account, were rather frequent in the Mughal realms. The “territories around Agra, Bayana and Delhi”, for example, were ravaged by a famine from 1554 to 56. Agra itself, the then capital of the Empire, was left “desolated with only some houses remaining.” “Severe scarcity” was the lot of Gujarat “some time (sic.) during the 1560s.” An “acute famine” broke out around Sirhind “in or about 1572-73.” Again, in 1574-75, there was a “serious famine” in Gujarat. Another great famine affected Gujarat and “most of the Dakhin” from 1630 to 1632. In 1636-37, “famine and scarcity” prevailed in Punjab. Then, a “prolonged period of scarcity” commenced in the North, very likely due to the depredations caused by the war of succession between Dara Shikoh and Aurangzeb. It lasted into the first “four or five years” of Aurangzeb’s reign. In 1671, an “acute famine ravaged the territory extending from the west of Banaras to Rajmahal.”

The land revenue levied in the Mughal Empire was very steep. Habib writes that, as per the instructions in the “revenue literature” of Aurangzeb’s reign, as also “the orders passed in certain cases”, the land revenue had to “everywhere amount to half the produce”. It appears that this extraordinarily high revenue demand was motivated “by a formal regard for the Shariat (Muslim law), which prescribes this as the maximum for kharaj(land tax).” Though “strength giving”, or taqavi, loans were advanced to the peasants to encourage cultivation, this very debilitating revenue demand must have generated some rural misery. In comparison, the revenue demand in ancient India was a lot more humane. For instance, the customary royal share of the produce in the Gupta Empire, termed bhaga, was “usually fixed at the rate of one-sixth”.

Why was the revenue demand so high under Mughal rule? This was because it was levied by two sets of people, both invested in exploiting the peasantry to the maximum – the jagirdars and the imperial authorities. All jagirdarsin the Mughal Empire were also mansab, or military rank, holders and were required to maintain a certain number of troopers from the revenues of their land assignments, or jagirs. The tendency of the jagirdars was to “set the revenue demand so high as to secure the greatest military strength of the empire.” It seems that they sought to extract the maximum from the peasants so as to have the financial resources to equip their troopers as best as possible. On the other hand, the imperial authorities’ revenue assessments approximated the surplus produce, “leaving the peasant just the barest minimum needed for subsistence.” Habib candidly admits that “It was this appropriation of the surplus produce that created the great wealth of the Mughal ruling class.” To make matters worse, since the jagirdars were periodically transferred and did not hold a land assignment for more than three or four years, they never followed “a far-sighted policy of agricultural development.” The jagirdar would, thus, resort to “any act of oppression that conferred an immediate benefit upon him.” Frequently, we are told by Habib, “peasants were compelled to sell their women, children and cattle in order to meet the revenue demand.” Another desperate measure that the peasants resorted to was flight – sometimes, they simply abandoned their lands and ran away, unable to bear the revenue burden. This phenomenon was “growing in momentum with the passage of years.” Equally commonly, peasants turned rebellious and defiant, refusing to pay the exorbitant revenue. There were even specific terms used in Mughal administration to describe the villages which “went into rebellion or refused to pay taxes” – these were called mawasor zor talab.

Overall, it ought to be apparent by now, the agrarian economy of the Mughal realms was not really in a flourishing state. As Bernier had observed, the ground was “seldom tilled otherwise than by compulsion.” And this was because a peasant in the Mughal Empire could not

“avoid asking himself this question: ‘Why should I toil for a tyrant who may come to-morrow (sic.) and lay his rapacious hands upon all I possess and value, without leaving me, if such should be his humour, the means to drag on my miserable existence?’”

Commodity Consumption in Mughal India

In the middle of the seventeenth century, when the Mughal Empire presented a glittering façade to the world, a significant development was afoot in Northwestern Europe. Commodity consumption was undergoing a spurt in that part of the world and diffusing through the social body. In simpler language, we see the beginnings over there of what we today term ‘consumerism’. In the Netherlands, for example, ever larger numbers of people were buying pocket watches, better quality furniture, chinaware, and paintings. This was on account of a concomitant rise in household incomes. These phenomena have been documented and examined in detail by Jan de Vries in a very interesting monograph titled The Industrious Revolution.

Do we see anything similar happening in contemporary Mughal ruled India? Like in the Netherlands, was commodity consumption turning into a broad-based phenomenon in our country back then? No, not at all. Kenneth Pomeranz, for example, points out that “there was a significant increase in luxury consumption in Mughal India”, but there was no emergent ““fashion system” with broad participation from many classes….” In simple language, he is saying that commodity consumption in the Mughal Empire was heavily skewed – the purchase of high-end goods was rising, but one does not notice a diversity of classes making their own distinct consumption choices. Pomeranz is thus unsure if one can“speak of rising popular consumption in India as comparable to that in” contemporary China, Japan, and Western Europe. And this was because the broad masses were just too impoverished for that. Disparities in the Mughal Empire, as revealed by the estimates of Pomeranz, were simply monstrous. He writes that in the year 1647 only “445 families received 61.5 percent of all revenues, which were about 50 percent of gross agricultural output….” No doubt, Europeans in India could not help but notice “its extremes of wealth and poverty.”

Conclusion

I shall keep this part very brief and precise – overall, it seems very erroneous to term Mughal India ‘rich’. In terms of living standards, India was already falling behind the better off parts of Europe. Mughal rule was characterized by the ruthless exploitation of the primary producers, namely, the artisans and the peasants. And there is scant evidence of ‘popular consumption’ in Mughal ruled India. Commodity consumption in the Mughal Empire was skewed in favor of the luxuries due to the poverty of the common masses. No, Mughal India was not ‘rich’, only the Mughal royalty and nobility were.

On Amazon’s alternative history thriller, The Man in the High Castle, viewers are taken into a CGI-world of a new Berlin that has grown in scale and grandeur to reflect its place as the center of a Thousand Year Reich that now covers most of the globe.

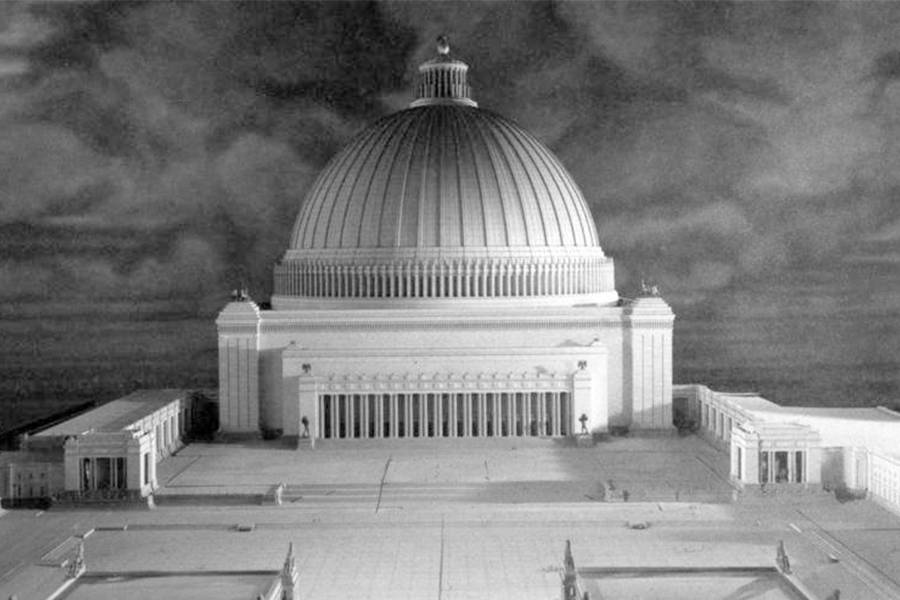

But rather than springing from the mind of filmmakers, this Nazi super-city is based on real plans conceived by Adolf Hitler and Albert Speer, the “General Building Inspector for the Reich Capital.” The project was started in 1937. A massive scale model was made, sections of Berlin were cleared, and its construction sites may have even initiated the Holocaust.

Hitler was determined this vision of a Nazi dystopia called Welthauptstadt Germania (World Capital Germania) would be finished by 1950. Speer had impressed Hitler with his work on buildings at Nuremberg, which were deliberate reinterpretations of classical architecture into massive, distinctly austere Nazi architecture designed to intimidate and overwhelm.

This aligned with Hitler’s vision to make Welthauptstadt Germania the grandest city of them all by taking the best monuments Europe had to offer and to super-size them. Most of these monuments would be placed along a seven-kilometer (4.3 miles) Boulevard of Splendours to create an overall narrative describing Nazi Germany’s superiority to citizens and visitors alike. At the south end of the boulevard, would sit the Triumphal Arch, designed to dwarf Paris’ Arc de Triomphe, which could fit inside Hitler’s planned arch six times. At the north end, the boulevard would open up into a parade ground featuring a colossal Fuhrer’s Palace, the Reich Chancellery, and the ridiculously massive Grand Hall.

Only a handful of buildings were constructed. Hitler’s Reich Chancellery was one, with its Long Hall twice as long as Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors, which inspired it. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in the bombing of Berlin in 1945. Another building was the stadium for the 1936 Berlin Olympics, built five miles from Berlin’s center. It was the largest in Europe, modeled off the Roman Colosseum, but 200 meters longer. After the game’s success, Hitler decided he needed a more massive arena, which, was it planned, would house every Olympic Games hence. It was only partially built.

The rest of Welthauptstadt Germania would be new ring roads, autobahns, tunnels and living areas. The environment would have been hostile to citizens. Traffic lights and tramways would be a thing of the past, forcing pedestrians underground into a system of tunnels just to cross the roads and negotiate the complex roadways.

The architecture would literally and metaphorically oppress its people.

Areas of residential Berlin were marked for development. Speer and his cronies had 60,000 apartments bulldozed and 100,000 Germans became homeless. The real suffering was once again directed at the Jews. There would be no place for them in this new city, so 25,000 apartments were seized from Jews. Evicted, they were sent to ghettos, then concentration camps, while homeless Germans were crammed into their apartments.

The Jews became the laborers. Speer apparently remarked: “The Yids got used to making bricks while in captivity in Egypt.”

Many believe the “Night of Broken Glass” in Nov. 1938 was the beginning of the Holocaust but it started months earlier with Germania’s construction.Gross-Rosen, Buchenwald, and Mauthausen concentration camps were built near quarries, while Sachsenhausen was built near a brickworks. Speer signed a contract with the SS to have all bricks shipped to Germania’s construction sites. Sachsenhausen was 35 kilometers from Berlin’s center, so canals ferried the quarried stone to the Welthauptstadt Germania construction sites. These brickworks proved the harshest labor in all camps. Literally, tens of thousands were worked to death.

The workforce of 130,000 included not only Jews but POWs. Then in June 1938, police started rounding up tramps, gypsies, homosexuals, and beggars off the streets to make up the labor force.

Hitler’s project was not without its critics. Speer’s number two, Hans Stefan drew a series of caricatures which parodied the overbearing nature of the Germania project in secret. Several drawings poke fun at the ridiculous size of the Grand Hall. One depicts Berlin’s largest building, the Reichstag, being accidentally moved by a crane during construction of the impossibly large Grand Hall.

Stefan does not hold back in criticising the changes to Berlin, which he sees as tampering with German history and culture. Hitler had the Victory Column relocated. Stefan’s response was to show the Goddess Victory, unhappy with Hitler’s decision, escaping via parachute from her fixture at the top of the column.

Construction on Welthauptstadt Germania finally ground to a halt as the Second World War progressed. Speer believed that Nazi victory was imminent and remarked that Allied air strikes on Berlin had helped to level the old city to pave way for Germania. They hadn’t.

Though Hitler committed suicide Albert Speer was luckier. At the Nuremberg Trials he charmed the court, and despite his heavy use of concentration camp labor, he denied knowledge of the Holocaust. Spared execution, he spent the next twenty years in Spandau prison.

Dig into the overgrown weeds of any old JRPG discussion thread on a gaming forum, or just peak at the manic diatribes game players scrawl onto Twitter today, and you’ll largely be told by people who’ve been dedicated to their controllers for decades that you need to play Chrono Trigger.

Going off mass critical reputation, Chrono Trigger probably ranks just under Final Fantasy 7, and the oldest of these Video Game Sages will tell you why Trigger‘s actually better than Final Fantasy 7, even if you didn’t ask!

Ultimately, this Chrono Trigger review wasn’t written to determine where it ranks in the imaginary pantheon of Japanese Role Playing Games any ‘real gamer has to play’. Unlike the overbearing chiding for not playing it yet delivered to you in a string of tweets by ‘SuperSaiyanCloud’, we’d like to point out this Hall of Famer is still perfectly playable and every bit as charming today.

There is no need for the nostalgia goggles.

The one-off Chrono Trigger came about after Final Fantasy creator Hironobu Sakeguchi and Dragon Quest creator Yuji Horii went on a research trip together in 1992 to study the newest developments in the world of computer graphics. We should mention some rando named Akira Toriyama who created some random cartoon called Dragon Ball had accompanied them, and they felt the spark to create something unique.

Development would begin the following year, with fellow heavyweight Nobuo Uematsu and future legends scriptwriter Masato Kato and composer Yasunori Mitsuda getting drafted along the way. The game’s original Super Nintendo release would manifest in early 1995 to instant acclaim. The game was essentially crafted by the JRPG supergroup to end all JRPG supergroups, and their combined talent, expertise, and artistic sensibilities still thoroughly shine when playing the game even now.

Being the diehards for these cretors that we are, we just had to write our own Chrono Trigger review.

Chrono Trigger launches quickly into what might be the most delightful introductory hour to any JRPG, using its colorful and since-iconic medieval festival setting to tease the player of the whimsy to come in their adventure. Like any Ye Olden Times town-wide celebratory affair, you’ve got your merry-making-men and your carnival games, but also giant fightable Neko Robots and a time machine that goes amok.

Immediately, a comic sense derived from Chrono Trigger’s joyful Dragon Quest lineage makes itself apparent, keeping the game light and refreshing, perfect for playing in hand-held bursts.

That haywire time machine, by the way, blasts Crono, our protagonist, and these other primo Toriyama cut-ups all throughout time. Cavemen times and Mad-Maxian futures alike are lovingly depicted via distinct pixel artwork that’s still quite stunning to eyes when you spend some time with it. The Jukebox’s worth of playful tunes from Nobuo Uematsu and Yoshinori Kitase fit these backdrops like a glove, and evoke a unique sense of place and time to each local you visit, often drawing from Final Fantasy’s unique Sci-Fi fantasy blend.

To be perfectly clear, with Chrono Trigger being a JRPG released in 1995, you’re going to have to stomach that oh so dreadful turn-based gameplay that Final Fantasy dropped after its first PS2 outing. This Chrono Trigger review can’t convince you to like that style of play if you don’t.

If you do like turn-based gameplay, or you are at least open to the idea after realizing you spent days fighting a giant monkey in Sekiro, the good news is that Chrono Trigger‘s one of the most approachable out there. Its real-timeturn-based system brings an active action bar to the game. That means that during a battle, the longer you take, the more turns the enemy will receive. If you now prefer a more relaxed approach, there is also the Wait mode, where if you’re in a command menu (like choosing an item or tech to use) time effectively stops.

The game also drops random battles entirely and instead incorporates fixed places for enemy locations on the map; your character levels will naturally progress as you travel through time. In other words, there is no need to grind.

Lots of the bosses have fun gimmicks that aren’t too difficult to figure out, which simulates some variety in your base JRPG gameplay. Honestly, if you enjoy Pokémon battles, you’ll be at home here.

Compared to a mainline Final Fantasy game, Chrono Trigger’s a little light on the story, less likely to jerk on your tears. However, you can actually beat this game in under 30 hours (if you don’t care about spending countless hours on discovering all twelve endings), with no time being wasted on grinding or nonsensical JRPG melodramatic convolution. Each minute in this relatively short adventure’s tight, every step through time precisely planned and impeccably designed.

Though you might not cry over what happens to party-friends Frog, Magus, and Ayla, you’ll come to treasure their peculiar company. They are much more lively than most SQUARE fare.

Many call Chrono Trigger a flawless game, and this 202X Century Chrono Trigger review doesn’t disagree with that assertion. It may be more limited in scope than its Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy cousins, but this concentrated bit of excellence feels especially fresh in today’s sequel- and remake-filled game climate.

You can play Chrono Trigger on PC and mobile, but we recommend hunting a DS copy if that’s an option for you.

One doesn’t need to search for long to discover that words like “totalitarian,” “fascist” and “political extremist” are all the rage nowadays. Most often they serve as little more than personal attacks, rather than accurate descriptions of the forces at play. To call an opponent a “fascist” is one of the most groan-inducing clichés of the modern times. While much can be said about each of these words, and what they actually mean, it is worth noting that while “fascist” has a very particular political and historical meaning, and the phrase “political extremism” is extremely relative, the word “totalitarian” literally has no meaning at all.

One could say that, like “fascist,” it has become a meaningless buzzword, but that would be incorrect, since unlike fascism it was always a meaningless buzzword meant to smear any system that doesn’t follow the liberal capitalist viewpoint, as we shall see below.

Where Does the Word Come From?

The word “totalitarianism” was brought into the popular consciousness by scholar and author Hannah Arendt in her first major work, the 1951 volume The Origins of Totalitarianism. The idea behind this book was that communism and fascism were both somehow connected, and formed the same sort of society, which was called the “totalitarian” society.

In Arendt’s hands, the major differences between the USSR and Nazi Germany disappeared. Her theory suggested that two completely different political and social ideologies can be considered fundamentally the same when compared with the author’s own—in this case, liberal capitalism, which is the only ideology put forward as not “totalitarian.”

Since then, media puppets, right-wing intellectuals and the ruling class in general have made great play with the word “totalitarianism,” a word that one hears blaring from every television.

The Theory of “Totalitarianism” is Unrealistic & Unscientific

Essentially, the term “totalitarianism” is not a scientific term, but simply a tool. Its place in history was on the side of capitalism when it sought to find a way to equate the USSR with Nazi Germany.

In fact, Arendt’s theory of “totalitarianism” has never measured up in the real world. There has never been a so-called “totalitarian” society, not even under the fascist dictatorships of Hitler and Mussolini, nor could one ever realistically exist.

It is quite odd to read Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism, because she has no understanding of how socialism and fascism work and grossly distorts them both.

For example, she offers literally no explanation as to why the USSR and Nazi Germany were on opposite sides during World War II, nor why Nazi Germany invaded the USSR, nor why the USSR entered the conflict even before the United States, or why 22-27 million Soviet soldiers and civilians lost their lives at the hands of the Nazis.

From the way she describes it, the Nazis and the Soviets should have been on the same side against the capitalist and liberal nations, putting aside for a moment the fact that fascism is actually a form of capitalism—a fact that, of course, she also ignores.

Did World War II, the single greatest conflict in all of human history, merely happen as a result of personality conflicts on the part of Stalin and Hitler? The fact that communists and fascists were on opposite sides and bitterly fighting against each other—all this is nowhere in the “totalitarian” analysis. All that it seen is a chauvinist attempt to mush everything together.

The Theory of “Totalitarianism” is Hypocritical

The word “totalitarian” is used often in place of, or as a supplement to, the word “dictatorship,” which actually does have a meaning. A dictatorship, or a rule by a single class unrestricted by any laws, can exist, such as the dictatorship of the proletariat, which is called “totalitarian.” However, liberal democracies are dictatorships of the bourgeoisie, and they are not called totalitarian.

The criteria often given by those that have a definition of “totalitarian” are:

What is notable about these above criteria? All of them also apply to liberal democracies. One only has to replace “dictator” with “capital” and “the government” with “capitalism.”

The last point here is the most controversial, since most loose definitions of totalitarianism come from the idea of the individual being subordinated to the collective. Individuals within capitalism are subordinate to money and the means by which it is made, in this case, by work. What a person can do within those societies depends on his or her ability to pay money and to work. Do scholars call capitalist countries totalitarian? No. It is word which serves no useful purpose except in propaganda.

Why Is Our Society Not Considered “Totalitarian?”

Money, profit and capital rule our society absolutely. Every aspect of our lives is subject to the will of capital. There can be no freedom of speech or religion, no freedom of the arts, and no freedom of the press insofar as capital exists. You can say anything you want, but without capital no one will hear you, and it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to figure out what will happen when you say something that becomes a threat to the existence of the ruling class. Take a look at what happened to the Black Panthers.

Take a look at what happened to Fred Hampton, George Jackson and Anna Mae Aquash. Take a look at Kent State, where the National Guard murdered unarmed student protesters.

You can worship whatever god you want, but does your religion actually free you from capital? You can draw, paint, sing, and create whatever you want, but if it doesn’t make a profit, how will you continue, and how often will you be able to do it? And if it is not in the interests of capital, how will you get an audience, and how big will that audience be? If the ruling class doesn’t like what you have to say, you will be silenced or more likely, never heard at all.

If art is not in the interests of capital, it will not be published, especially if it goes against those interests. And the press is, by and large, owned by capital itself.

The whole definition put forward of both totalitarianism and “political extremism” only has value within the camp of capitalist ideology. The concept is simply an invention of reactionary intellectuals in the NATO bloc.

Four months after the government-commissioned Brereton report said there was “credible evidence” of Australian war crimes in Afghanistan, including the murder of at least 39 civilians and prisoners, and multiple acts of torture, the perpetrators remain in the military. No investigations for criminal prosecutions have begun.

This is only the starkest expression of an ongoing cover-up involving the Liberal-National Coalition government, the Labor Party opposition, multiple state agencies and the official media. For years they have sought to hide evidence of the atrocities, which occurred under a Labor government between 2009 and 2013.

The Brereton report was a damage-control operation, initiated after some details were leaked to the media. It suppressed more information than it revealed and absolved governments and senior military command of any responsibility, based on the implausible assertion that they had been unaware of the crimes. The report’s release was greeted by brief hand-wringing from politicians and the media over the impact that the revelations would have on “our military.” The issue was then dropped almost entirely.

It resurfaced at a Senate estimates hearing on Monday. Chris Moraitis, director-general of the Office of the Special Investigator, established at the recommendation of the Brereton report to conduct a criminal investigation into the allegations, provided an update on the progress of its work.

In short, Moraitis indicated that the body he heads has done virtually nothing. The organisation does not even have any investigators.

“We’re in the process of engaging investigators and we’re going to do that in the next one, two, three months,” Moraitis said. “That involves them being sworn in as special members of the Australian Federal Police and involves at least three weeks of induction in preparation, and involves us also doing a few other things.”

Moraitis is clearly working to a timetable prepared by the government. After the report’s release last November, Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton and other government representatives declared that any criminal prosecutions, if they eventuated at all, would likely take up to a decade. These statements had the character of a directive rather than a prediction.

Moraitis’ comments underscored the character of the Brereton report, as a continuation of the cover-up. Conducted in secret, it was dragged out from 2016 to 2020. Investigators provided an untold number of military personnel with immunity for testimony, and much of the evidence was given on the proviso that it could not be used in a court. This was justified on the pretext of encouraging witnesses and participants in the crimes to testify freely.

The overwhelming majority of the material remains classified. The publicly-released version of the report contains few details that had not been previously reported in the media. Its descriptions of the war crimes were as vague as possible.

The main outcome of the Brereton investigation was to create a potential legal minefield, as to what evidence is admissible and what is not. Moraitis said his staff were sifting through the Brereton material to “help ensure investigators will only receive information they can lawfully obtain and use in criminal investigations and any future criminal proceedings.” This process is being conducted under a shroud of secrecy.

Moraitis’ testimony followed a report in the Murdoch-owned Daily Telegraph on March 16, which revealed that at least some of the 25 soldiers implicated in the war crimes remain in the military. The alleged criminals would not be sacked. They would be allowed to discharge from the army on unspecified “medical grounds.” No other media outlet picked up the story.

The article, apparently based on information provided from within the military, appeared just days before the Coalition, Labor, the Greens and other MPs voted for a royal commission into the treatment of military veterans and their high rates of suicide. The timing indicates that the hardships faced by soldiers, resulting from their deployment to predatory and illegal wars, will be exploited to obfuscate the criminality of what occurred in Afghanistan.

As for the victims and their relatives, the Coalition government stated after the release of the Brereton report that it did not intend to provide them with any compensation. A Google search indicates that the issue was last mentioned in the corporate media in December.

The obvious attempts to forestall any criminal prosecutions of the soldiers involved are all the more extraordinary, given that millions of people have seen cast-iron evidence of at least some of the crimes.

Last March, for instance, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation published footage from a soldiers’ helmet camera, showing the point-blank execution of an unarmed Afghan civilian in 2012. Had the murder occurred in any other context, the perpetrator would have been arrested, charged and sentenced years ago. Military whistleblowers, as well as Afghan victims, have also provided eyewitness accounts of some of the crimes to the media.

The bid to prevent the cases from ever reaching a court is motivated by several factors. When the report was released, some of the soldiers implicated indicated through the press that they felt “betrayed” and “scapegoated.” Shortly after, an image was leaked to the media, showing a senior special forces commander drinking beer from the prosthetic leg of a dead Afghan.

It was rapidly revealed that the man pictured was warrant officer John Letch. When he stood down after the publication, Letch was the Command Sergeant Major of Special Operations Command. Letch had worked at Army Headquarters and Headquarters Special Operations Command.

Whoever leaked the image of Letch, it was directed against the claim of the Brereton report that no one above the level of squadron command was aware of the violations of international law. The government and military command are undoubtedly fearful that if soldiers are tried, they will testify that they were merely following orders.

Many of the murders occurred after the Labor government of Prime Minister Julia Gillard ordered greater involvement of Australian troops in US-led “kill and capture” raids, supposedly targeting insurgent leaders in 2011.

In April 2013, then Chief of the Defence Force General David Hurley issued a secret directive to soldiers, warning that they could be “exposed to criminal and disciplinary liability, including potentially the war crime of murder” if they could not prove that those they killed were participating in hostilities. In other words, the crimes flowed from the government-led prosecution of a neo-colonial war, and were known to military command.

Clearly, there are also concerns that the true scale of the war crimes could be revealed if the alleged perpetrators are pressed in court. The Brereton inquiry acknowledged that there were likely many more incidents that were not covered in its report.

The latest proof that murder and torture were commonly used instruments of the occupation was provided by Shamsurahman Mamond, who worked as a translator for the Australian military in Uruzgan Province.

Mamond told the Special Broadcasting Service this week: “[In the] provincial reconstruction team, it was our job to connect with local elders and local people. They were coming and telling us what was going on out in the fields. They would say, ‘They’re destroying the whole house. They’re killing the kids and ladies and everyone because they’re looking for insurgents and Taliban.’”

The translator indicated that torture was routine at the Australian base in the town of Tarin Kowt. “My accommodation was a few metres away from the jail,” he said. “I saw sometimes they were taking people out of the car like toys, we also sometimes heard people yelling, it was sad because if someone is in the detention centre, they don’t have a weapon, they are not a threat anymore, there was no necessity for punishment.”

Such information runs counter to the promotion of the military by the entire political and media establishment, and preparations for its involvement in new and even greater crimes.

The last major media mention of the war crimes came in December, when Zhao Lijian, a Chinese foreign ministry representative, tweeted a condemnation of the killings. This was accompanied by a graphic, produced by a visual artist, showing an Australian soldier holding a knife to the neck of an Afghan child. The picture clearly referred to an incident described in the Brereton report, involving soldiers slashing the throats of two 14-year-old boys.

Labor, the Liberal-Nationals, the Greens and various independents all denounced Zhao’s tweet as a Chinese “attack” on Australian soldiers. The media treated the tweet as a far more serious offence than the killings themselves.

The hysterical reaction was a warning that ongoing exposure of the military was beyond the pale and would be treated as treasonous and “un-Australian.” This was directed against anti-war opposition, and was the signal for the war crimes to be dropped entirely from the press.

The denunciation of China also highlighted the fact that the cover-up of the war crimes is aimed at ensuring that the atrocities committed in Afghanistan do not get in the way of the preparations for Australia to play a frontline role in US plans for a catastrophic war against China.