The historic town of Samarkand is a crossroad and melting pot of the world’s cultures. Founded in the 7th century B.C. as ancient Afrasiab, Samarkand had its most significant development in the Timurid period from the 14th to the 15th centuries. The major monuments include the Registan Mosque and madrasas, Bibi-Khanum Mosque, the Shakhi-Zinda compound and the Gur-Emir ensemble, as well as Ulugh-Beg’s Observatory.

Brief synthesis

The historic town of Samarkand, located in a large oasis in the valley of the Zerafshan River, in the north-eastern region of Uzbekistan, is considered the crossroads of world cultures with a history of over two and a half millennia. Evidence of settlements in the region goes back to 1500 BC, with Samarkand having its most significant development in the Temurid period, from the 14th to the 15th centuries, when it was capital of the powerful Temurid realm.

The historical part of Samarkand consists of three main sections. In the north-east there is the site of the ancient city of Afrosiab, founded in the 7th century BC and destroyed by Genghis Khan in the 13th century, which is preserved as an archaeological reserve. Archaeological excavations have revealed the ancient citadel and fortifications, the palace of the ruler (built in the 7th century displays important wall paintings), and residential and craft quarters. There are also remains of a large ancient mosque built from the 8th to 12th centuries.

To the south, there are architectural ensembles and the medieval city of the Temurid epoch of the 14th and 15th centuries, which played a seminal role in the development of town planning, architecture, and arts in the region. The old town still contains substantial areas of historic fabric with typical narrow lanes, articulated into districts with social centres, mosques, madrassahs, and residential housing. The traditional Uzbek houses have one or two floors and the spaces are grouped around central courtyards with gardens; built in mud brick, the houses have painted wooden ceilings and wall decorations. The contribution of the Temurid masters to the design and construction of the Islamic ensembles were crucial for the development of Islamic architecture and arts and exercised an important influence in the entire region, leading to the achievements of the Safavids in Persia, the Moghuls in India, and even the Ottomans in Turkey.

To the west there is the area that corresponds to the 19th and 20th centuries expansions, built by the Russians, in European style. The modern city extends around this historical zone. This area represents traditional continuity and qualities that are reflected in the neighbourhood structure, the small centres, mosques, and houses. Many houses retain painted and decorated interiors, grouped around courtyards and gardens.

The major monuments include the Registan mosque and madrasahs, originally built in mud brick and covered with decorated ceramic tiles, the Bibi-Khanum Mosque and Mausoleum, the Shakhi-Zinda compound, which contains a series of mosques, madrasahs and mausoleum, and the ensembles of Gur-Emir and Rukhabad, as well as the remains of Ulugh-Bek’s Observatory.

Criterion (i): The architecture and townscape of Samarkand, situated at the crossroads of ancient cultures, are masterpieces of Islamic cultural creativity.

Criterion (ii): Ensembles in Samarkand such as the Bibi Khanum Mosque and Registan Square played a seminal role in the development of Islamic architecture over the entire region, from the Mediterranean to the Indian subcontinent.

Criterion (iv): The historic town of Samarkand illustrates in its art, architecture, and urban structure the most important stages of Central Asian cultural and political history from the 13th century to the present day.

Integrity

The different historic phases of Samarkand’s development from Afrosiab to the Temurid city and then to the 19th century development have taken place alongside rather than on top of each other. These various elements which reflect the phases of city expansion have been included within the boundaries of the property. The inscribed property is surrounded by more recent developments, of which parts are in the buffer zone. Afrosiab has been partly excavated and the Temurid and European parts of the city are being conserved as living historic urban areas.

The main listed monuments are well maintained. Some of the medieval features have been lost, such as the city walls and the citadel, as well as parts of the traditional residential structures especially in areas surrounding major monuments. Nevertheless, it still contains a substantial urban fabric of traditional Islamic quarters, with some fine examples of traditional houses.

Notwithstanding, there are several factors that can render the integrity of the property vulnerable that require sustained management and conservation actions.

Authenticity

The architectural ensembles of Samarkand as well as archaeological remains of Afrosiab have preserved all characteristic features related to the style and techniques and have maintained the traditional spatial plans of the urban quarter. However, inadequate restoration interventions as well as the challenges faced in controlling changes, particularly the construction of modern buildings, and the modernization on private properties have affected the authenticity of the property and make the property vulnerable to further changes.

Protection and management requirements

There are adequate legal provisions for the safeguarding of the heritage property. The State Samarkand Historical Architectural Reserve was established under the Decree of the Cabinet of Ministers of the Republic of Uzbekistan (26 May 1982). Within the Reserve all construction and development work is done according to the recommendations of the Samarkand Regional Inspection on Preservation and Restoration of Objects of Cultural Heritage.

The overall responsibility of the management of protected areas is with the Ministry of Cultural and Sport Affairs and the Samarkand provincial government. The operating bodies that influence the conservation and management of the property include the Ministry of Culture and Sports of the Republic of Uzbekistan and the Principal Scientific Board for Preservation and Utilization of Cultural Monuments, the Municipalities of the Samarkand Region and Samarkand city, the Samarkand Regional State Inspection on Protection and Utilization of Cultural Heritage Objects. Decisions on construction/reconstruction within the protective Reserve of Samarkand are taken in consultation with the Samarkand Regional State Inspection on Protection and Utilization of Monuments, or by the Scientific Board on Protection and Utilization of Monuments in Samarkand. Major projects receive approval at the national level.

The Regional State Inspection on Protection and Utilization of Cultural Heritage is in charge of day-to-day activities related to the monuments such as registration, monitoring, technical supervision of conservation and restoration, or technical expertise of new projects, these are implemented by the Scientific Board on Protection and Utilization of Monuments in Samarkand, which is obtaining the function of a Coordinating Committee and should have the main role to bring together all parties with interest in the conservation and development of Samarkand. Taking into account a scope and a complexity of issues facing the property, site management system could be strengthened through an operational unit.

The sustained implementation of the Management Plan is needed to ensure to further improve the cooperation between the various national and local authorities and set international standards for conservation. Several factors that can pose a threat to the conditions of integrity and authenticity of the property need to be systematically addressed through the implementation of an integrated conservation strategy, that follows internationally accepted conservation standards, as well as through the enforcement of regulatory measures. The management system will need to be integrated into other planning tools so that the existing urban matrix and morphology of the world heritage property are protected.

Funding is provided by the State budget, extra-budgetary sources and sponsorship. Resources needed for all aspects of conservation and development of the property should be secured to ensure the continuous operation of the management system.

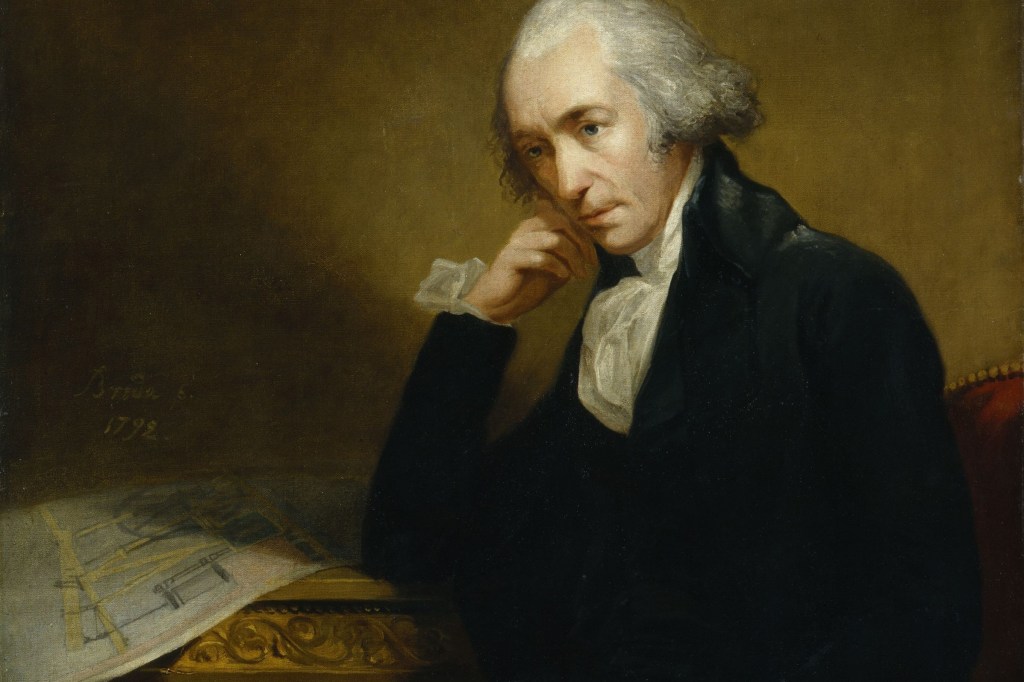

James Watt (January 19, 1736 – August 25, 1819) was a Scottish inventor and engineer whose improvements to the steam engine provided much of the impetus for the Industrial Revolution. His invention brought the engine out of remote coalfields and into factories, where work could be performed on large scales, almost year-round, with vastly higher efficiency. The steam engine was employed in the locomotive and steamboat, thus leading to the revolution in transportation. In addition, higher demands for precise machining led to a cascade of tools that were used to produce better machines. At the same time, Watt’s steam engine focused attention on the processes of converting heat to mechanical work. It inspired Sadi Carnot’s groundbreaking work on the efficiency of heat engines, leading to the development of the field of physics known as thermodynamics.

Early years

Watt was born on January 19, 1736, in Greenock, a seaport on the Firth of Clyde, in Scotland. His grandfather was a surveying and navigation instructor, while his father manufactured nautical instruments and was a shipwright, shipowner, and contractor. Watt’s mother, Agnes Muirhead, came from a distinguished family and was well-educated. Both his parents were Presbyterians.

Watt attended school irregularly, primarily because he suffered from migraine headaches. Because of this infirmity, he received most of his schooling at home. Watt’s father set up a small workbench for his son, who earnestly learned and practiced the skills of woodworking, metalworking, instrument making, and model making. He exhibited great manual dexterity and an aptitude for mathematics.

When he was seventeen, his mother died and his father’s health had begun to fail. Watt traveled to Glasgow and was apprenticed to an optician. He then headed for London on the advice of a friend, and studied instrument-making there for a year. Although he learned his trade, the unfavorable work environment strained his health and forced him to return to Scotland, where he convalesced. After his recovery, he attempted to establish himself as an instrument-maker in Glasgow. Despite there being no other mathematical instrument-makers in Scotland, the Glasgow Guild of Hammermen (any artisans using hammers) blocked his certification because he had not served at least seven years as an apprentice.

Watt was saved from this impasse by professors at the University of Glasgow, who in 1757, offered him the opportunity to set up a small workshop within the university. One of the professors, the prominent physicist and chemist Joseph Black, became Watt’s friend and mentor.

In 1764, just as he was about to make a major improvement to the Newcomen engine, Watt married his cousin, Margaret Miller, with whom he would have five children, two of whom would survive to adulthood.

Watt’s first wife died in childbirth in 1773, and in 1776, he married his second wife, Ann MacGregor.

Besides improving the steam engine, Watt took up other pursuits. In the 1880s, he experimented with the application of chlorine compounds to the bleaching process. He also was the first to propose the compound structure of water, although its constituent elements, oxygen and hydrogen, were not identified until years later, by French scientist Antoine Lavoisier.

Personality

Watt was an enthusiastic inventor, with a fertile imagination that sometimes got in the way of finishing his works, because he could always see “just one more improvement.” He was skilled with his hands and also able to perform systematic scientific measurements that could quantify the improvements he made and produce a greater understanding of the phenomenon he was working with.

Watt was a gentleman, greatly respected by other prominent men of the Industrial Revolution. He was a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Royal Society of London, a member of the Batavian Society, and one of only eight Foreign Associates of the French Academy of Sciences. He was also an important member of the Lunar Society, and was a much sought after conversationalist and companion, always interested in expanding his horizons. He was a rather poor businessman, and especially hated bargaining and negotiating terms with those who sought to utilize the steam engine. Until he retired, he was always much concerned about his financial affairs, and was something of a worrier. His personal relationships with his friends and partners were always congenial and long-lasting.

Later years

Watt retired in 1800, the same year that his partnership with Boulton expired, along with the patent rights to the steam engine. The famous partnership was transferred to the men’s sons, James Watt, Jr. and Matthew Boulton. William Murdoch, a long-time employee of the firm, was made a partner, and the firm prospered.

Watt continued to produce and patent other inventions before and during his semi-retirement. He invented a new method of measuring distances by telescope, a device for copying letters, improvements in the oil lamp, a steam mangle, and a machine for copying sculpture.

He died in his home, “Heathfield,” in Handsworth, Staffordshire, on August 25, 1819, at the age of 83.

Steam engine

In 1761, four years after opening his workshop, Watt began to experiment with steam after his friend, Professor John Robison, called his attention to it. At this point, Watt had still never seen an operating steam engine, but he tried constructing a model. It failed to work satisfactorily, but he continued his experiments and began to read everything about steam that he could get his hands on. He independently discovered the importance of latent heat—the heat absorbed or released without a change in temperature when a substance moves among the states of solid, liquid, or gas—in understanding the engine. Unknown to Watt, Black had famously discovered the principle some years before. Watt learned that the university owned a model Newcomen engine, but it was in London for repairs.

Named after its inventor, Thomas Newcomen, the Newcomen engine had been around since 1705, without being significantly improved, and had been applied with success to the removal of ground water from coal mines.

The Newcomen engine worked by filling a piston chamber with steam, which would then be condensed by sprinkling cold water into the chamber. The condensing steam would produce a vacuum, which pulled the piston down. The downward movement pulled down one arm of a beam, the upward movement of the other arm of which would be connected to machinery, such as a pump to remove water from a coal mine. The process would be repeated, thus creating a repetitive see-saw action that moved the pivoted beam up and down.

Watt convinced the university to have its broken model of the Newcomen engine returned, and made the repairs himself in 1763. It barely worked, and after much experimentation he showed that about eighty percent of the heat of the steam was consumed in heating the the piston cylinder.

Watt’s critical insight was to add a separate chamber, called the condenser, that was connected to the piston cylinder by a pipe. Condensation of the steam would occur in the condenser, thus allowing the temperature of the piston cylinder to be maintained at that of the injected steam and the heat loss minimized. In 1765, Watt produced his first working model based on this principle.

Then came a long struggle to produce a full-scale engine. This required more capital, some of which came from Black. More substantial backing came from John Roebuck, the founder of the celebrated Carron Iron Works, near Falkirk, with whom he now formed a partnership. But the principal difficulty was in machining the piston and cylinder. Iron workers of the day were more like blacksmiths than machinists, so the results left much to be desired. Much capital was spent in pursuing the ground-breaking patent, which in those days required an act of parliament.

Strapped for resources, Watt was forced to take up employment as a civil engineer in 1866, work he would do for eight years until more capital to develop and manufacture his inventions became available. In 1767, Watt traveled to London to secure the patent on his new invention, which was granted in 1769. In the meantime, Roebuck went bankrupt, and Matthew Boulton, who owned the Soho foundry works near Birmingham, acquired his patent rights. Watt and Boulton formed a hugely successful partnership which lasted for the next twenty-five years.

During this period, Watt finally had access to some of the best iron workers in the world. The problem of manufacturing a large cylinder with a tightly fitting piston was solved by John Wilkinson, who had developed precision boring techniques for cannon-making at Bersham, near Wrexham, North Wales. Finally, in 1776, the first engines were installed and working in commercial enterprises. These first engines were used for pumps and produced only reciprocating motion. Orders began to pour in, and for the next five years Watt was very busy installing more engines, mostly in Cornwall, for pumping water out of mines.

The field of application of the improved steam engine was greatly widened only after Boulton urged Watt to convert the reciprocating motion of the piston to produce rotational power for grinding, weaving, and milling. Although a crank seemed the logical and obvious solution to the conversion, Watt and Boulton were stymied by a patent for this, whose holder, John Steed, and associates proposed to cross-license the external condenser. Watt adamantly opposed this, and they circumvented the patent with their sun and planet gear in 1781.

Over the next six years, Watt made a number of other improvements and modifications to the steam engine. A double acting engine, in which the steam acted alternately on the two sides of the piston was one. A throttle valve to control the power of the engine, and a centrifugal governor to keep it from “running away” were very important. He described methods for working the steam expansively. A compound engine, which connected two or more engines was described. Two more patents were granted for these in 1781 and 1782. Numerous other improvements that made for easier manufacture and installation were continually implemented. One of these included the use of the steam indicator, which produced an informative plot of the pressure in the cylinder against its volume, which he kept as a trade secret. These improvements taken together produced an engine which was about five times as efficient in its use of fuel as the Newcomen engine.

Because of the danger of exploding boilers and the ongoing issues with leaks, Watt was opposed at first to the use of high pressure steam. Essentially, all of his engines used steam at near atmospheric pressure.

In 1794, the partners established Boulton and Watt, to exclusively manufacture steam engines. By 1824, it had produced 1164 steam engines. Boulton proved to be an excellent businessman, and both men eventually made fortunes.

Controversy

As with many major inventions, there is some dispute as to whether Watt was the original, sole inventor of some of the numerous inventions he patented. There is no dispute, however, that he was the sole inventor of his most important invention, the separate condenser. But it was his practice (from around the 1780s) to preempt others’ ideas that were known to him by filing patents with the intention of securing credit for the invention for himself, and ensuring that no one else was able to practice it.

Some argue that his prohibitions on his employee, William Murdoch, from working with high pressure steam on his steam locomotive experiments delayed its development. Watt and Boulton battled against rival engineers such as Jonathan Hornblower, who tried to develop engines which did not fall afoul of their patents.

Watt patented the application of the sun and planet gear to steam in 1781, and a steam locomotive in 1784, both of which have strong claims to have been invented by Murdoch. Murdoch never contested the patents, however, and remained an employee of Boulton and Watt for most of his life. Boulton and Watt’s firm continued to use the sun and planet gear in their rotative engines long after the patent for the crank expired in 1794.

Legacy

James Watt’s improved steam engine transformed the Newcomen engine, which had hardly changed for 50 years, into a source of power that transformed the world of work, and was the key innovation that brought forth the Industrial Revolution. A significant feature of Watt’s invention was that it brought the engine out of the remote coal fields into factories, where many mechanics, engineers, and even tinkerers were exposed to its virtues and limitations. It was a platform for generations of inventors to improve. It was clear to many that higher pressures produced in improved boilers would make engines with greater efficiency, and would lead to the revolution in transportation that was soon embodied in the locomotive and the steamboat.

The steam engine made possible the construction of new factories that, since they were not dependent on water power, could be placed almost anywhere and work year-round. Work was moved out of the cottages, resulting in economies of scale. Capital could work more efficiently, and manufacturing productivity greatly improved. New demand for precise machining produced a cascade of tools that could be used to produce better machines.

In the realm of pure science, Watt’s steam engine focused attention on the processes of converting heat to mechanical work. It inspired Sadi Carnot’s groundbreaking paper on the efficiency of heat engines, which led to the development of the field of physics known as thermodynamics. The unit of power that Watt developed and adopted, the horsepower, is the power expended in lifting 33,000 pounds through one foot in one minute. The watt is an alternative unit of power named after James Watt. One horsepower is equivalent to 745.7 watts.

Memorials

Watt was buried in the grounds of St. Mary’s Church, Handsworth, in Birmingham. Later expansion of the church, over his grave, means that his tomb is now buried inside the church. A statue of Watt, Boulton, and Murdoch is in Birmingham. He is also remembered by the Moonstones and a school is named in his honor, all in Birmingham. There are over 50 roads or streets in the UK named after him. Many of his papers are in Birmingham Central Library. Matthew Boulton’s home, Soho House, is now a museum, commemorating the work of both men.

The location of James Watt’s birth in Greenock is commemorated by a statue close to his birthplace. Several locations and street names in Greenock recall him, most notably the Watt Memorial Library, which was begun in 1816 with Watt’s donation of scientific books, and developed as part of the Watt Institution by his son. The institution ultimately became the James Watt College. Taken over by the local authority in 1974, the library now also houses the local history collection and archives of Inverclyde, and is dominated by a large seated statue in the vestibule. Watt is additionally commemorated by statuary in George Square, Glasgow, and Princes Street, Edinburgh.

The James Watt College has expanded from its original location to include campuses in Kilwinning (North Ayrshire), Finnart Street and The Waterfront in Greenock, and the Sports campus in Largs. The Heriot-Watt University near Edinburgh was at one time the “Watt Institution and School of Arts” named in his memory, then merged with George Heriot’s Hospital for needy orphans and the name was changed to Heriot-Watt College. Dozens of university and college buildings (chiefly of science and technology) are named after him.

The huge painting, James Watt Contemplating the Steam Engine, by James Eckford Lauder, is now owned by the National Gallery of Scotland.

Watt was ranked first, tying with Edison, among 229 significant figures in the history of technology by Charles Murray’s survey of historiometry presented in his book, Human Accomplishments. Watt was ranked 22nd in Michael H. Hart’s list of the most influential figures in history.

Silent Hill 2 is one of the most meticulously detailed, wonderfully crafted video games to ever exist. Today, I want to talk about all the details, both big and small, that I love about one of my favourite video games.

In the latest Top Ten episode on the Star Geek channel, I delve into the Worst Special Edition Changes. From CGI mishaps, to completely new scenes, these are the absolute worst changes brought upon the Star Wars Saga.

Even Yoda would have been proud at this spectacle.

Cara Delevingne, Mindy Kaling, Zoe Saldana and a flock of other celebrities took to social media to share snaps of themselves dressed as Star Wars characters to celebrate the highly anticipated opening of The Force Awakens, the seventh film in the iconic franchise, on Thursday.

And Cara probably won the award for the day’s geekiest costume.

The beautiful British model was completely unrecognisable as the green, slug like alien Jabba the Hutt as she stood inside a theatre lobby, wielding two lightsabers.

The 23-year-old captioned it: ‘Watching Star Wars in style’ although how she intended to sit on her long tail was a moot point.

Mindy Kaling was another star who really got inside her character, dressed up as Hans Solo’s Wookiee sidekick Chewbacca for her holiday card.

The 36-year-old also included one of the new additions to the Star Wars family – Chewy’s son Lumpy – in her photo.

‘Happy holidays from our family to yours. Love, Chewy and Lumpy,’ she wrote on the Instagram image.

Country stars Tim McGraw, 48, and his wife Faith Hill, also 48, planned a surprise for their daughters, Gracie, 18, Maggie, 17, and 14-year-old Audrey on Thursday morning.

Tim dressed up as a member of evil Supreme Chancellor Palpatine’s elite Red Guard, while Faith assumed full battle pose as one of the rebels.

Tim captioned his Instagram snap: ‘Happy @starwars Day!!! This is how we woke up our kids!! #TheForceAwakens.’

‘The Force is strong in this household,’ according to Zoe Saldana, 37, who posted a cute picture with artist husband, Marco Perego, and their one-year-old twins, Bowie and Cy.

All were seen from the knees down wearing socks featuring a different character from the film.

UFC star and actress Ronda Rousey captioned her snap: ‘About last night… Star Wars was awesome… I’m a little short for a Stormtrooper.’

The 28-year-old was joined by friends in impressive Darth Maul and Boba Fett costumes to take in the hotly anticipated film.

Meanwhile Facebook entrepreneur Mark Zuckerberg and his wife Priscilla Chan swaddled their newborn daughter Max in a Jedi cloak as she lay between a fluffy Wookiee, Darth Vader’s black mask, new Droid BB-8 and a baby-sized lightsaber.

He captioned it, predictably: ‘The Force is strong with this one.’

Chrono Cross was released in 1999 and developed by square. As the follow up to one of the greatest RPGs of all time, Chrono Trigger, this sequel had a lot to live up to. So does this game live up to the lofty legacy left by Chrono Trigger? Well that’s a difficult question because of how different and unique Chrono Cross is when compared to Trigger, or any other RPG for that matter. So let’s take a look with this review at all the interesting aspects of the game and see if it hits that same masterpiece level that its predecessor did…