Now reading Captain Breakneck by Louis Henri Boussenard…

On March 21, 2017, CNN published an article on a new study from the American Journal of Public Health that found the average life span of an autistic person is 36 years. I wasn’t shocked by this news. I know how dire things can be for so many of us on the spectrum, but that number struck me for a very specific reason. I had just turned 35 the previous month.

Since I learned this news, I’ve been anticipating the milestone of turning 36 with a mix of confusion, dread, and a host of other feelings I can’t quite articulate. I’ve had more existential episodes than usual, brooding about the meaning of life. It’s been a lot like a midlife crisis — except that (I kept thinking) my own midlife might have happened as long as half my life ago. The average age of death for autistic people who live to adulthood might be older than 36 (and as of now, there is still no age-specific data). Still, the figure from the research journal haunted me.

At some point between that moment and now, I made a pair of promises to myself:

The good news is that I have officially, as of 8:35 am Eastern on February 7, made it.

The bad news is that living while autistic doesn’t always leave one with much energy to write all of the meaningful things that you want to write to improve your life and the lives of other people like you.

Turning 36 scared the shit out of me. I want the fact that autistic people die so much earlier than the average American to scare the shit out of you too.

Here’s why that number is so low — and all the ways I’m lucky to have made it to 36

Some caveats. First: Not all studies on autism and mortality agree on the average age of our deaths. If you think I’m being overly dramatic by picking one that appears to cite the youngest age, here are some other recent studies with more positive results. One says 39 is the average life span; another says 54. By “positive,” though, I mean “studies that determined autistic people live longer, on average, than 36, but still found that we die significantly earlier than our non-autistic counterparts.”

Second, whenever I write about autism, there’s always someone who shows up to point out that I’m not really autistic enough to count or that I’m not the kind of autistic person that people are thinking about when they think of the tragedies and pressures that face people on the spectrum.

Because I can speak, work, and maintain a semblance of a social life — and because I am able to hide my most severe symptoms from other people — they assume that I am too “high-functioning” to be considered autistic. Before that happens here, let me say that, yes, I am probably at a lower risk of death than many autistic people. Not because I’m “higher-functioning” or because my autism is mild, but because I happened to be born into a certain body and a certain set of circumstances.

For example, the study that CNN cites, “Injury Mortality in Individuals With Autism,” primarily focuses on — as you can guess from the title — death from injury. As a child, I was never a wanderer (as many autistic children are), which put me at a low risk for drowning and other related deaths. I’ve had seizures, but I don’t have epilepsy (as many autistic people do), which puts me at a lower risk of death.

I also don’t have to worry that my incredibly supportive parents will murder me for being too much of a burden to them. That makes me luckier than others with my condition. More than 550 disabled people have been murdered by their parents, relatives, or caregivers in the past five years in the United States, according to the Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

“We see the same pattern repeating over and over again,” ASAN says of the grisly phenomenon. When disabled children are killed, the media focuses on the “burden” that the murderer faced in having to care for them. People sympathize with them instead of the victim. And in the worst cases, this can lead to lighter sentencing.

There are also ways that I am safer than many of my fellow autistic people that we don’t yet have the statistics for but that I can definitely see in the world right now. As a cisgender white woman, I do not worry that I’ll be killed by the police like 15-year-old Stephon Edward Watts or 24-year-old Kayden Clarke. Nor will I have to suffer the serious long-term health effects that this kind of constant fear and dehumanization can have.

The stress of living with autism is exhausting

You can’t entirely separate my incredibly privileged and lucky autistic ass from these devastating statistics. Autistic adults who don’t have a learning disability, like me, are still nine times more likely to die from suicide than our non-autistic peers. Autistica, a UK charity, explores some of the complex reasons that might be behind this alarmingly high suicide rate in a report on “the urgent need for a national response to early death in autism.” Or you can just take a look at my own laundry list of issues to get the general idea:

I’m tired all the time. The coping mechanisms that I developed as a bullied and undiagnosed child — from learning to mimic the behaviors of people who are more naturally likable than me to holding entire conversations where I reveal nothing about myself for fear of being too enthusiastic, too annoying, too overbearing, or simply too much — are not great for managing a remotely healthy life or building self-esteem. The effort it takes to fit in is increasingly exhausting as I get older.

All that hard work to make other people more comfortable around me feels more and more pointless. I appreciate that I have people in my life who have assured me that I can just be myself, but unlearning almost 36 years of shitty coping mechanisms and performances also takes a buttload of work. My sleeping patterns, due to anxiety and possibly to autism itself, are erratic at best.

I value the social and career gains that I made when I had more energy and inclination to blend into society. I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was old enough to read, and I’m now lucky enough to survive on writing alone. But with it has come chronic anxiety, which seems to increase exponentially. There is, however, one calculation that I’m always doing in my head: whether my contributions to my family, friends, and the world are at least equal to all that I feel like I’m taking from it. I always feel like I’m at a deficit.

I repeatedly have to tell people I’m not a math savant. I’m tired of watching people who aren’t on the spectrum tell shitty versions of our stories while I can’t find the funding or the audience to tell my own. I’m tired of watching people get feels and inspiration from shows like The Good Doctor while they can’t seem to give a shit about autistic people in real life.

I’m so, so sick of watching people pay lip service to the value of autistic life while funding research into prenatal testing for autism at one end and supporting euthanasia for autism on the other, all in the name of preventing suffering. As if these measures that suggest that autistic birth should be prevented — or that they have a duty to die if they are too much of a “burden” on their loved ones — don’t make me feel worthless.

Even when I’m not actively struggling with any of the above, there’s the constant stress and anxiety. My resting heart rate is in the 90s. My body aches in ways that I can’t entirely attribute to age. My energy level appears to be similarly deteriorating.

This should not be a good enough outcome for any autistic person. We all deserve better than this.

So what do I want you to do about it?

I’ve spent my whole life being told that non-autistic people are so brilliant and intuitive when it comes to social issues. Like many autistic people, though, I haven’t always felt like I’ve seen much empathy, compassion, or understanding. And the evidence is starting to suggest that we’re not wrong about the level of judgment and stereotyping we face.

If you want to understand people on the spectrum, I’d recommend starting with some of the following: Listen to us. Invest in our work. Invest in science and actions that actually make our lives better now instead of chasing a hypothetical cure. Don’t kill us. Think twice about sympathizing with the parents who do kill us. Don’t rush to armchair-diagnose every mass murderer with autism — like what happened with the most recent Florida school shooting. Give your money to marginalized autistic people instead of charities like Autism Speaks, which dedicate only a small percentage of their budget to programs that will actually help autistic people. Think about how hard we’re working to exist in your world and consider meeting us halfway.

Tell us we don’t bore you. Tell us we don’t drain you. Look at us somewhere other than the eyes — we’re really not comfortable with eye contact and are tired of being forced to make it for your benefit — and tell us that we deserve to be alive.

And then act like it.

Many people with autism experience a triad of trauma: neglect at home, abuse from trusted adults and bullying at school or work.

The bullying began early. When she was just 5, Kassiane Asasumasu remembers other children taking her belongings and lying about it because they knew that she was face-blind and would not be able to tell on them. At a slumber party when she was 10, girls poked her, froze her underwear and made a game of seeing how many times they could make her cry. Her post-slumber-party meltdown lasted 48 hours. The following year, classmates locked her in a locker — and then she got in trouble for kicking the door open.

“Most of my childhood memories are of other kids being mean to me,” says Asasumasu, who was diagnosed with autism when she was 3. “I cried every day of elementary school.” Some days, she cried so hard that she threw up. Even when she didn’t give in to tears, the insults gutted her.

In middle school, teachers told her mother they thought she was at risk of suicide, but beyond that, she did not feel that the adults in her life ever supported her. Her teachers encouraged her to ignore her tormentors, but she was unable to do so. At home, where she says her seven siblings often blamed her for their transgressions, her parents punished her rather than them. “You’re the one always getting in trouble,” says Asasumasu, who is now 37, “for what everybody else did.”

Experiences like Asasumasu’s are a terrible reality for many autistic people. Studies suggest that children on the spectrum are up to three times as likely as their neurotypical peers to be targets of bullying and physical or sexual abuse. Such maltreatment can cause severe stress and trauma, yet it often goes unrecognized or unreported. Therapies to help treat trauma in people with autism are mostly experimental, so these individuals are often left to fend for their own safety and health. “Children with autism who have experienced maltreatment or some form of violence are a very vulnerable population, not only because they’re more likely to experience these maltreatment experiences, but we also know very little about how to best support them,” says Christina McDonnell, assistant professor of clinical psychology at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in Blacksburg.

One important way to develop better support systems, she and other experts say, is to listen to autistic people about how society harms them. “What we need to do is some of the hard work to find out what’s happening in these systems that allows this to take place,” says Catherine Corr, assistant professor of special education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “And I think information from folks who have lived that would be really beneficial to understanding how systems have failed them.”

Maltreatment is an umbrella term that includes neglect and emotional, physical and sexual abuse. That children with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to maltreatment has been replicated in studies going back decades. Studies specific to autistic children are much scarcer. As a graduate student studying child abuse in 2014, McDonnell observed developmental problems, including autism, in a significant proportion of children with maltreatment cases under investigation by U.S. state social-services departments. But she saw a disconnect in the scientific literature: Studies of traumatic stress in instances of maltreatment rarely considered the children’s autism diagnoses. And autism researchers had barely begun to explore the possible maltreatment of their study participants.

The few studies that had been done offered mixed results. Some suggested that children with autism are more likely than their typical peers to be neglected or abused, and more likely to be involved with child protective services, the state departments in the United States tasked with overseeing children’s well-being. Others did not show an association between autism and an elevated risk of abuse, although the studies had limitations — including being small or using outdated definitions of autism.

McDonnell and her colleagues decided to investigate the link and tapped into autism surveillance data, as well as records from the South Carolina Department of Social Services. They compared patterns of abuse and neglect for nearly 5,000 children with and without autism born from 1992 to 1998. They found that nearly one in five autistic children in the state, and one in three with both autism and intellectual disability, have been reported to be maltreated. Even after adjusting for factors such as low family income and limited parental education, children with autism remain up to three times as likely as their neurotypical peers to experience maltreatment, the team reported in 2018. “We were alarmed by those numbers and how high they were,” McDonnell says.

Neglect in particular is a problem for children with autism, as well as for those with intellectual disability. Neglect is the most common type of maltreatment documented by child protective services, says Kristen Seay, assistant professor of social work at the University of South Carolina in Columbia. Exacerbating the problem is the fact that children with autism often have needs that families with few resources may find difficult to meet.

McDonnell’s team found that autistic children are also vulnerable to physical abuse. Primary caregivers in the immediate family are the most common perpetrators of the abuse, but a broader range of offenders — including family members, babysitters and childcare providers — may be more likely to target children with autism or intellectual disability than other children.

A similar story emerged in Tennessee. Researchers there analyzed data from an autism monitoring site run by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and found that having autism more than doubles a child’s chances of referral to child protective services. The study included more than 24,000 children born in 2006 and found that 17 percent of the 387 autistic children had been the subject of calls to the state’s child abuse hotline, compared with 7 percent of the others. Despite the higher number of reports, however, child protection professionals investigated the caregivers of only 62 percent of the autistic children, compared with 92 percent of typical children. “We really need to have a heightened awareness that this represents a tremendously vulnerable population,” says lead researcher Zachary Warren, a clinical psychologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

When Nancy Nestor’s son P. was 3, a year before he was diagnosed with autism, he came home from preschool, went to his room and, as he played, muttered to himself, “Stupid P. Stupid P.,” over and over. (We are using P.’s first initial only, to protect his privacy.) At the time, P. did not know what ‘stupid’ meant, but Nestor was heartbroken. She spoke with his teacher, who was shocked. The teacher had not heard students using that word and promised to listen for it — and put an end to the problem. But Nestor continued to worry: Her son did not talk much, so he could not tell her if the bullying continued. “Nobody wants to hear someone refer to their child as stupid, especially a child that can’t talk,” she says.

In the years that followed, P. occasionally encountered bullies, including a group of boys in high school who threw their balled-up paper lunch bags at him and told him to throw them away. But he also received compassion and support from classmates, teammates (he was on the track team) and coaches. Now 22, P. attends community college and lives at home. Nestor still listens to him talk to himself to find out what is happening in his life.

Physical attacks by peers may leave autistic children with wounds on their faces, shoulder displacements and large scratches on their body, says Daniel Hoover, a child and adolescent psychologist at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. In a 2018 review of studies, Hoover and a colleague found that children with autism are bullied three to four times as often as those without disabilities, including their own siblings: 40 to 90 percent of children with autism are bullied, compared with 10 to 40 percent of typical children, according to various studies.

Parents sometimes notice instances of bullying that their autistic children might not. When P. was in elementary school, for example, his peers made him the designated prisoner in a game of ‘cops and robbers.’ A middle-school yearbook years later included a picture of him in a stockade during a field trip to Colonial Williamsburg, a museum in Williamsburg, Virginia. The selection stung Nestor because multiple adults must have had to approve that picture, which she felt preserved P. as the “weird kid” for posterity. “It’s not bullying, but it sure is on that slippery slope,” Nestor says. “He didn’t understand. He was just happy to be included.”

The opposite can also happen: Some research suggests that children with autism tend to consider a broader range of behaviors offensive than their parents do. About two years ago, Hoover worked with an autistic teenager who was devastated because a boy at school had made fun of the New England Patriots, his favorite professional football team. All the peer had to do to set him off was say, “Deflategate,” referring to the allegation that the team’s quarterback, Tom Brady, had ordered the deflation of footballs used in a playoff game in 2014. The boy “couldn’t even function; he could not get over it,” Hoover says. To an outsider, trash-talking a football team might seem more like banter than bullying. But for this boy, it was extremely upsetting.

Some people with autism find even everyday experiences stressful because they see the world literally and may not pick up on the nuances of what people say or do, causing them to lose their ability to trust when people say one thing but do something else. “There’s a kind of chronic potential trauma of being in a world where you understand 50 percent of what’s going on most of the time because you’re missing all these social cues, so you’re feeling constantly out of the loop and having chronic stress around that,” says Connor Kerns, a psychologist who runs the Anxiety Stress and Autism program at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

Studies show that children who are introverted or anxious are even more likely to experience trauma from maltreatment than are those who are more socially active and outgoing. Lacking a social network may exacerbate the problem. Autistic children without intellectual disability may be particularly vulnerable, experts say, because they are more aware of and socially sensitive to interpersonal nuances than those who have intellectual disability. On top of it all, many autistic children are quick to react strongly when treated poorly. “They blow up, they freak out, they run, they yell, they get angry,” Hoover says. “And that might set them up as targets some more because they get a huge reaction out of the kids.”

Abusers have their own reasons for choosing autistic children as targets. Chief among them is that children on the spectrum often lack the communication skills to report abuse — or to be believed if they do. Seay remembers one young girl with a developmental disability who told her family that she was being sexually abused at school. The girl’s parents told the school administrators, but both parties doubted her story until a typically developing sibling reported that the same thing had also been happening to her. A physical exam of the sibling corroborated her account. “Individuals who exploit and abuse children know which children are more likely to be a good victim — to not say anything, to have difficulty communicating what is going on, and then even if they do, it’s going to be said that the child has lied before,” Seay says. Compounding the problem is the fact that autistic children are exposed through service systems to many different adults, raising the chances of encountering someone who will mistreat them.

Abuse of autistic children may also persist either because educators are not trained to recognize its signs in these children or because they are afraid of making things worse for the children if they say something, Corr says. “Often times, there is this fear that by reporting a child to the child-welfare system, a child with a disability will actually be worse off,” she says. “If folks in child welfare aren’t necessarily trained to think about kids with disabilities, what will happen to that kiddo once they enter that system?”

In one of Asasumasu’s earliest and most painful memories, she is a 3-year-old facing a teacher who wraps her legs around the preschooler’s chair to prevent her from going anywhere. The teacher gives instructions: “Sit. Stand. Look at me.” If Asasumasu follows the instructions, she earns a fraction of an M&M. If not, the teacher pulls her body into position or forces her eyes open.

The technique, part of a standard type of autism therapy, has become contentious. Critics have compared it to gaslighting in abusive relationships because it teaches children to comply and perform specific behaviors for rewards instead of speaking out when they feel uncomfortable. Many adults have been vocal about their traumatic memories of undergoing this type of treatment as children. “My earliest memories are of adults prying my eyes open and making me look at them,” Asasumasu says. “To this day, if somebody says, ‘Look at me,’ it’s like, ‘I’m never looking at you again.’”

Maltreatment can cause lasting damage, leading to severe stress, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Most studies have not shown an increased incidence of PTSD among autistic people. That may be because the PTSD criteria were not written for people with autism or because trauma in this group is more likely to lead to anxiety, depression and other mental health issues than to PTSD, Kerns says. What’s more, there are no reliable tools for screening autistic children for trauma, which is defined as an event or events that affect a person negatively, sometimes in an ongoing way.

Meanwhile, researchers are crafting therapies. Hoover, for example, is adapting a technique called trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy. The 12-week program aims to get children talking about what happened to them and to teach them how to manage their fears around those experiences. Because many children with autism may not understand verbal instructions or remember what they are supposed to practice outside of therapy, Hoover created visual schedules for them to keep at home and ramped up involvement by caregivers. The modified program also enlists children’s special interests — say, Spider-Man or Harry Potter — to help them tell their stories.

The modified method appears to help — at least anecdotally, Hoover says. Parents are reporting positive results, and autistic children who undergo the therapy are showing improved scores on the UCLA Child/Adolescent PTSD Reaction Index, a self-report questionnaire that screens for PTSD in children and teenagers. Hoover is writing a manual for the technique and says he gets multiple inquiries each week from centers around the world that want training. He and his colleagues have been collecting data on the therapy from several dozen children for the past year, and they have plans for a controlled trial.

McDonnell, meanwhile, is preparing to measure the potential benefits of the standard trauma technique on children with autism. Other teams are trying community and grassroots programs that aim to teach people about abuse, sexuality and other topics to help them stay safe.

Many autistic people come up with their own strategies. Adrienne Lawrence, a 36-year-old attorney and author in Los Angeles, California, learned she has autism about a year ago. But she has long known that she operates on logic rather than nuance to decipher her world. If, for example, a man trying to date her tells her his mother died, she assumes that simply means his mother died, and she misses that he is trying to sleep with her by playing on her sympathy. If he apologizes and says he will not lie again, she assumes he means it. The reason autistic people face so much abuse, Lawrence says, is that so many non-autistic people lie, not that autistic people miss those lies.

Lawrence has always created rules to help her navigate the world and has adopted new ones since learning she is on the spectrum. For example, she has developed specific guidelines to help her spot and avoid sexual harassment, which she has experienced at work, including specifying which types of behavior are appropriate in different situations. “Previously, I would use my 10 years of criminology study to do a statistical and logical analysis in my head as to whether it was safe to enter a man’s home, considering the facts particular to the specific situation. Now I do not rely so heavily on stats and logic but simply ensure meetings are in public places.”

For Asasumasu, life started to get better in high school, when she learned to fight back. She also befriended students she calls “weird” and “scary,” which kept bullies away. She now studies aikido, a defensive martial art that helps her wait to assess a situation before judging whether it is a threat, though she has continued to experience abusive relationships into adulthood.

Like Lawrence, she relies on pattern recognition to predict and avoid abuse. “Somebody who is rude to waiters and mean to pets is definitely going to try to hit you at some point,” she says.

Ultimately, Asasumasu says, it is society, not autistic people, that must change. “We should be able to deal with the fact that there’s more than one way of being,” she says. “For all the kinds of civility you hear in the general world, you never hear, ‘Hey, maybe don’t be a jerk to people who are different from you.’”

Granville Street is a major street in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada, and part of Highway 99. Granville Street is most often associated with the Granville Entertainment District and the Granville Mall. This street also cuts through suburban neighborhoods like Shaughnessy, and Marpole via the Granville Street Bridge.

The community was known as “Gastown” (Gassy’s Town) after its first citizen – Jack Deighton, known as “Gassy” Jack. “To gas” is period English slang for “to boast and to exaggerate”. In 1870 the community was laid out as the “township of Granville” but everybody called it Gastown. The name Granville honours Granville Leveson-Gower, 2nd Earl Granville, who was British Secretary of State for the Colonies at the time of local settlement.

In 1886 it was incorporated as the city of Vancouver, named after Captain George Vancouver, who accompanied James Cook on his voyage to the West Coast and subsequently spent 2 years exploring and charting the West Coast.

During the 1950s, Granville Street attracted many tourists to one of the world’s largest displays of neon signs.

Towards the middle of the twentieth century, the Downtown portion of Granville Street had become a flourishing centre for entertainment, known for its cinemas (built along the “Theatre Row,” from the Granville Bridge to where Granville Street intersects Robson Street), restaurants, clubs, the Vogue and Orpheum theatres, and, later, arcades, pizza parlours, pawn stores, pornography shops and strip clubs.

By the late 1990s, Granville Street suffered gradual deterioration and many movie theatres, such as “The Plaza, Caprice, Paradise, [and] Granville Centre […] have all closed for good,” writes Dmitrios Otis in his article “The Last Peep Show.” In the early 2000s, the news of the upcoming 2010 Winter Olympic Games, to be hosted in Whistler, a series of gentrification projects, still undergoing as of 2006, had caused the shutdown of many more businesses that had heretofore become landmarks of the street and of the city.

Also, Otis writes that “once dominated by movie theatres, pinball arcades, and sex shops [Downtown Granville is being replaced] by nightclubs and bars, as […it] transforms into a booze-based ‘Entertainment District’.” In April 2005, Capitol 6, a beloved 1920s-era movie theatre complex (built in 1921 and restored and reopened in 1977) closed its doors (Chapman). By August 2005, Movieland Arcade, located at 906 Granville Street became “the last home of authentic, 8 mm ‘peep show’ film booths in the world” (Otis). On July 7, 2005, the Granville Book Company, a popular and independently owned bookstore was forced to close (Tupper) due to the rising rents and regulations the city began imposing in the early 2000s in order to “clean up” the street by the 2010 Olympics and combat Vancouver’s “No Fun City” image. (Note the “Fun City” red banners put up by the city on the lamp-posts in the pizza-shop photograph). Landlords have been unable to find replacement tenants for many of these closed locations; for example, the Granville Book Company site was still boarded up and vacant as of July 12, 2006.

While proponents of the Granville gentrification project in general (and the 2010 Olympics in specific) claim that the improvements made to the street will only benefit its residents, the customers frequenting the clubs and the remaining theatres and cinemas, maintain that the project is a temporary solution, since the closing down of the less “classy” businesses, and the build-up of Yaletown-style condominiums in their place, will not eliminate the unwanted pizzerias, corner-stores and pornography shops – and their patrons – but will simply displace them elsewhere (an issue reminiscent of the city’s long-standing inability to solve the problems of the DTES).

Robert Owen (May 14, 1771, Newtown, Powys – November 17, 1858) was a Welsh utopian socialist and social reformer, whose attempts to reconstruct society widely influenced social experimentation and the cooperative movement. The innovative social and industrial reforms which he introduced at his New Lanark Mills during the early 1800s made it a place of pilgrimage for social reformers and statesmen from all over Europe. He advocated the elimination of poverty through the establishment of self-sustaining communities, and experimented with such a utopian community himself at New Harmony, Indiana, from 1825 to 1828.

Owen believed that a man’s character was completely formed by his environment and circumstances, and that placing man under the proper physical, moral, and social influences from his earliest years was the key to the formation of good character and to the amelioration of social problems. Owen’s doctrines were adopted as an expression of the workers’ aspirations, and he became a leader of the trade union movement in England, which advocated control of production by the workers. The word “socialism” first became current in the discussions of the “Association of all Classes of all Nations,” which Owen formed in 1835.

Early Life

Robert Owen was born in Newtown, Montgomeryshire (Wales) on May 14, 1771, the sixth of seven children. His father was a saddler and ironmonger who also served as local postmaster; his mother came from one of the prosperous farming families of Newtown. Owen attended the local school where he developed a strong passion for reading. At the age of ten, he was sent to seek his fortune in London with his eldest brother, William. After a few weeks, Owen found a position in a large drapery business in Stamford (Lincolnshire) where he served as an apprentice. After three years he returned to London where he served under another draper. His employer had a good library, and Owen spent much of his time reading. Then, in 1787 or 1788, he moved to Manchester in the employ of Mr. Satterfield, a wholesale and retail drapery merchant.

Owen now found himself in what would soon become the capital city of the English Industrial Revolution, just as factories were being built and textile manufacture expanding. He was a serious, methodical young man who already possessed an extensive knowledge of the retail aspect of his chosen trade. In late 1790 he borrowed £100 from his brother William and set up independently with a mechanic named Jones as a manufacturer of the new spinning mules. After a few months he parted with Jones and started business on his own with three mules as a cotton spinner. During 1792, Owen applied for and was appointed manager of Peter Drinkwater’s new spinning factory, the Piccadilly Mill, where he quickly achieved the reputation as a spinner of fine yarns, thanks to the application of steam power to the mule. One of Drinkwater’s most important clients was Samuel Oldknow, maker of fine muslins. Drinkwater had intended Owen to become a partner in his new business by 1795, but a projected marriage alliance between Drinkwater’s daughter and Oldknow caused the cancellation of the agreement with Owen. Hurt and unwilling to remain a mere manager, Owen left Piccadilly Mill in 1795.

Owen was approached by Samuel Marsland, who intended to develop the Chorlton estate in Manchester, but instead he found partners in two young and inexperienced businessmen, Jonathan Scarth and Richard Moulson, who undertook to erect cotton mills on land bought from Marsland. Marsland assisted the three young partners. Owen made use of the first American sea island cotton (a fine, long-staple fibre) ever imported into England, and made improvements in the quality of the cotton being spun. In 1796, the financial basis of the company was broadened with the inclusion of Thomas Atkinson, to create the Chorlton Twist Company, which in 1799 negotiated the purchase of David Dale’s New Lanark mills.

Philanthropy in New Lanark (1800)

Richard Arkwright and David Dale had planned the industrial community at New Lanark in 1783, to take advantage of the water power of the Falls of Clyde deep in the river valley below the burgh of Lanark, 24 miles upstream from of Glasgow. The factory of New Lanark began production in 1791. About two thousand people were associated with the mills; 500 of them were children who were brought at the age of five or six from the poorhouses and charities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. The children had been well treated by Dale, who safeguarded heir welfare, but the general condition of the people was very unsatisfactory. Many of the workers came from the poorest levels of society; theft, drunkenness, and other vices were common; education and sanitation were neglected; and most families lived in only one room. The respectable country people refused to submit to the long hours and demoralizing drudgery of the factories.

By 1800, there were four mills, making New Lanark the largest cotton-spinning complex in Britain, and the population of the village (over 2,000) was greater than that of Lanark itself. Dale was progressive both as a manufacturer and as an employer, being especially careful to safeguard the welfare of the children.

Owen first met David Dale by chance, through an introduction by the daughter of his friend, Robert Spear, to Dale’s eldest daughter, Caroline. During a visit to Glasgow he fell in love with Caroline. Owen was interested to learn that Dale wanted to sell New Lanark to someone who would continue his humane policy toward the children. Owen’s willingness to do so was probably responsible for both Dale’s agreeing to sell to the Chorlton Twist Company and also his consent to the marriage of Owen and Caroline in the fall of 1799.

Owen induced his partners to purchase New Lanark, and after his marriage with Caroline in September 1799, he set up home there. By 1800, there were four mills, making New Lanark the largest cotton-spinning complex in Britain, and the population of the village (over 2,000) was greater than that of Lanark itself. Owen was manager and part owner, and, encouraged by his great success in the management of cotton factories in Manchester, he hoped to conduct New Lanark on higher principles, not only on commercial principles.

Though at first the workers regarded the stranger with suspicion, he soon won their confidence. His paternalism was more rigorous than that of his frequently absent partner, Dale. The mills continued to be commercially successful, but some of Owen’s schemes involved considerable expense, which displeased his partners. Tired at last of the restrictions imposed on him by men who wished to conduct the business on ordinary principles, Owen formed a new firm in 1813, partnering with Jeremy Bentham and a well-known Quaker, William Allen. The investors in his firm, content with a 5 percent return on their capital, were willing to allow more freedom for Owen’s philanthropy.

Through New Lanark, Owen’s reputation as a philanthropist was established. The village remained much as Dale had organized it; more living space was created and higher standards of hygiene were enforced. Owen’s primary innovation at new Lanark was the public buildings which demonstrated his concern for the welfare of his workers: the New Institution for the Formation of Character (1816); the Infant School (1817) which enabled mothers to return to work when their children reached the age of one year; and the Store, which increased the value of the workers’ wages by offering quality goods at prices just slightly higher than cost.

At New Lanark, Owen involved himself in education, factory reform, and the improvement of the Poor Laws. His first public speech, in 1812, was on education, and was elaborated upon in his first published work, The First Essay on the Principle of the Formation of Character (1813). Together with three further essays (1813-1814), this comprised A New View of Society, which remains Owen’s clearest declaration of principles.

For the next few years Owen’s work at New Lanark continued to attract national and even European attention. His schemes for the education of his workpeople were enacted in the opening of the institution at New Lanark in 1816. He was a zealous supporter of the factory legislation resulting in the Factory Act of 1819, which, however, greatly disappointed him. He had interviews and communications with the leading members of government, including the premier, Lord Liverpool, and with many of the rulers and leading statesmen of Europe. New Lanark itself became a place of pilgrimage for social reformers, statesmen, and royal personages, including Nicholas, later emperor of Russia. According to the unanimous testimony of all who visited it, New Lanark appeared singularly good. The manners of the children, brought up under his system, were beautifully graceful, genial and unconstrained; health, plenty, and contentment prevailed; drunkenness was almost unknown, and illegitimacy occurred extremely rarely. The most perfect good feeling subsisted between Owen and his workers, and all the operations of the mill proceeded with the utmost smoothness and regularity. The business was a great commercial success.

Owen had relatively little capital of his own, but his skillful management of partnerships enabled him to become wealthy. After a long period of friction with William Allen and some of his other partners, Owen resigned all connection with New Lanark in 1828.

Plans for Alleviating Poverty Through Socialism (1817)

Gradually Owen’s ideas led him from philanthropy into socialism and involvement in politics. In 1817, he presented a report to the committee of the House of Commons on the Poor Law. The general misery, and stagnation of trade consequent on the termination of the Napoleonic Wars, was engrossing the attention of the entire country. After tracing the special causes, connected with the wars, which had led to such a deplorable state of the economy and society, Owen pointed out that the permanent cause of distress was to be found in the competition of human labor with machinery, and that the only effective remedy was the united action of men, and the subordination of machinery.

His proposals for the alleviation of poverty were based on these principles. Communities of about 1,200 persons each should be settled on quantities of land from 1,000 to 1,500 acres (4 to 6 km²), all living in one large building in the form of a square, with public kitchen and mess-rooms. Each family should have its own private apartments, and the entire care of the children till the age of three, after which they should be brought up by the community, their parents having access to them at meals and all other proper times.

These communities might be established by individuals, by parishes, by counties, or by the state; in every case there should be effective supervision by duly qualified persons. Work, and the enjoyment of its results, should be in common. The size of his communities was probably suggested by his village of New Lanark; and he soon proceeded to advocate such a scheme as the best form for the re-organization of society in general.

In its fully developed form, the scheme did not change much during Owen’s lifetime. He considered an association of from 500 to 3,000 as the fit number for a good working community. While mainly agricultural, it should possess all the best machinery, should offer every variety of employment, and should, as far as possible, be self-contained. “As these townships” (as he also called them) “should increase in number, unions of them federatively united shall be formed in circles of tens, hundreds and thousands,” till they should embrace the whole world in a common interest.

Owen’s plans for the cure of pauperism were received with considerable favor until, at a large meeting in London, Owen explicitly declared his hostility to revealed religion. Many of his supporters believed that this action undermined his support among the upper classes. Owen’s denunciation of religion evoked a mounting campaign against him which in later years damaged his public reputation and the work associated with his name. His last substantial opportunity to secure official approval for his scheme came in 1820, when he produced his Report to the County of Lanark in which his communitarian and educational theories were blended with David Ricardo ‘s labor theory of value.

Community Experiment in America (1825)

At last, in 1825, such an experiment was attempted under the direction of his disciple, Abram Combe, at Orbiston near Glasgow. The next year Owen bought 30,000 acres of land in Indiana (United States) from a religious community, renamed it New Harmony and began an experiment of his own. After a trial of about two years, both failed completely. Neither of them was an experiment with paupers; the members came from many different backgrounds; worthy people with the highest aims were mixed with vagrants, adventurers, and crotchety, wrongheaded enthusiasts, and were, in the words of Owen’s son “a heterogeneous collection of radicals… honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in.”

Under Owen’s guidance, life in the community was well-ordered for a time, but differences soon arose over the role of religion and the form of government. Numerous attempts at reorganization failed, though it was agreed that all the dissensions were conducted with an admirable spirit of cooperation. Owen withdrew from the community in 1828, having lost £40,000, 80 percent of all he owned. Owen took part in another experimental community for three years in Great Britain at Tytherly, Hampshire (1839–1845); he was not directly concerned in its formation or in another experiment at Ralahine, County Cork (1831–1833). The latter (1831) proved a remarkable success for three and a half years until the proprietor, having ruined himself by gambling, had to sell out. Tytherly, begun in 1839, failed absolutely.

Josiah Warren, one of the participants in the New Harmony Society, asserted that community was doomed to failure due to a lack of individual sovereignty and private property. He says of the community:

We had a world in miniature — we had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result. …It appeared that it was nature’s own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us …our “united interests” were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation… (Periodical Letter II 1856)

Warren’s observations on the reasons for the community’s failure led to the development of American individualist anarchism, of which he was its original theorist.

Trade Union Movement

In his “Report to the County of Lanark” (a body of landowners) in 1820, Owen had declared that reform was not enough, and that a transformation of the social order was necessary. His proposals for self-sufficient communities attracted the younger workers who had been brought up under the factory system. Between 1820 and 1830, a number of societies were formed and journals were establisheded which advocated his views. The growth of labor unionism and the emergence of the working-class into politics caused Owen’s doctrines to be adopted as an expression of the workers’ aspirations, and when he returned to England from New Harmony in 1829 he found himself regarded as their leader. The word “socialism” first became current in the discussions of the “Association of all Classes of all Nations,” which Owen formed in 1835. During these years, his teaching gained such influence among the working classes that the Westminster Review (1839) stated that his principles were the actual creed of a great portion of them.

In the unions, Owenism stimulated the formation of self-governing workshops. The need for a market for the products of such shops led to the formation of the National Equitable Labour Exchange in 1832, applying the principle that labor is the source of all wealth. Exchange was effected by means of labor notes; this system superseded the usual means of exchange and middlemen. The London exchange lasted until 1833, and a Birmingham branch operated for only a few months until July 1833.

The growth of labor unions made it seem possible that all the various industries might some day be organized by them. Owen and his followers carried on a propaganda campaign all over the country, which resulted in the new National Operative Builders Union turning itself into a guild to carry on the building industry, and the formation of a Grand National Consolidated Trades Union in 1834. However, determined opposition from employers and severe restrictions imposed by the government and law courts suppressed the movement within a few months.

After 1834 Owen devoted himself to propagating his ideas on education, morality, rationalism, and marriage reform. By 1846, the only permanent result of Owen’s agitation, zealously carried on in public meetings, pamphlets, periodicals, and occasional treatises, remained the co-operative movement, and for a time even that seemed to have utterly collapsed. In his late years, Owen became a firm believer in spiritualism. He died at his native town on November 17, 1858.

Thought and Works

Owen’s thought was shaped by the Enlightenment, the exposure to progressive ideas in Manchester as a member of the Literary and Philosophical Society, and the Scottish Enlightenment. From an early age, he had lost all belief in the prevailing forms of religion, and had developed his own explanation for the existence of social evils. Owen’s general theory was that man’s character is formed by his environment and circumstances over which he has no control, and that he should therefore neither be praised nor blamed for his condition. He concluded that the key to the formation of good character was to place man under the proper influences, physical, moral, and social, from his earliest years.

These principles, the irresponsibility of man and of the effect of early influences, formed the basis of Owen’s system of education and social amelioration. They were embodied in his first work, four essays entitled A New View of Society, or Essays on the Principle of the Formation of the Human Character, the first of which appeared in 1813. In Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race, Owen asserted and reasserted that character is formed by a combination of Nature or God and the circumstances of the individual’s experience. Owen felt that all religions were “based on the same absurd imagination” which he said made mankind “a weak, imbecile animal; a furious bigot and fanatic; or a miserable hypocrite.”

Labor Reforms

Owen had originally been a follower of the classical liberal and utilitarian Jeremy Bentham. However, whereas Bentham thought that free markets (in particular, the right for workers to move and to choose their employers) would free the workers from the excess power of the capitalists, Owen became more and more socialist as time passed.

At New Lanark, Owen instituted a number of reforms intended to improve the circumstances of workers and to increase their investment in the products of their labor. Many employers operated the “truck system,” whereby all or part of a worker’s salary was paid in tokens which had no value outside the factory owner’s “truck shop.” The owners were able to supply shoddy goods to the truck shop and still charge top prices. A series of “Truck Acts” (1831-1887) stopped this abuse. The Acts made it an offence not to pay employees in common currency. Owen opened a store where the people could buy goods of sound quality at little more than cost, and he placed the sale of alcohol under strict supervision. He sold quality goods and passed on the savings from the bulk purchase of goods to the workers. These principles became the basis for the co-operative shops in Britain that continue to trade today.

To improve the production standards of his workers, Owen installed a cube with different colored faces above each machinist’s workplace. Depending on the quality of the work and the amount produced, a different color was displayed, so that all the other workers could see who had the highest standards, and each employee had an interest in doing his best. Owen also motivated his workers by improving the living conditions at New Lanark for the workers and their families.

His greatest success, however, was in the education of the young, to which he devoted special attention. He was the founder of infant schools in Great Britain. Though his ideas resemble the efforts being made in Europe at the time he probably arrived at them on his own.

Children

Robert and Caroline Owen’s first child died in infancy, but they had seven surviving children, four sons and three daughters: Robert Dale (born 1801), William (1802), Anne Caroline (1805), Jane Dale (1805), David Dale (1807), Richard Dale (1809) and Mary (1810). Owen’s four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale and Richard, all became citizens of the United States. Anne Caroline and Mary (together with their mother, Caroline) died in the 1830s, after which Jane, the remaining daughter, joined her brothers in America, where she married Robert Fauntleroy.

Robert Dale Owen, the eldest (1801-1877), was for long an able exponent in his adopted country of his father’s doctrines. In 1836-1839 and 1851-1852, he served as a member of the Indiana House of Representatives and in 1844-1847 was a Representative in United States Congress|Congress, where he drafted the bill for the founding of the Smithsonian Institution. He was elected a member of the Indiana Constitutional Convention in 1850 and was instrumental in securing to widows and married women control of their property and the adoption of a common free school system. He later succeeded in passing a state law giving greater freedom in divorce. From 1853 to 1858, he was United States minister at Naples. He was a strong believer in spiritualism and was the author of two well-known books on the subject: Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World (1859) and The Debatable Land Between this World and the Next (1872).

Owen’s third son, David Dale Owen (1807-1860), was in 1839 appointed a United States geologist who made extensive surveys of the north-west, which were published by order of Congress. The youngest son, Richard Owen (1810-1890), became a professor of natural science at Nashville University.

Red Square (Russian: Красная площадь, romanized: Krasnaya ploshchad’) is one of the oldest and largest squares in Moscow, the capital of Russia. Owing to its historical significance and the adjacent historical buildings, it is regarded as one of the most notable and important squares in Europe and the world. It is located in Moscow’s historic centre, in the eastern walls of the Kremlin. It is the city landmark of Moscow, with famous buildings such as Saint Basil’s Cathedral, Lenin’s Mausoleum and the GUM. In addition, it has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1990.

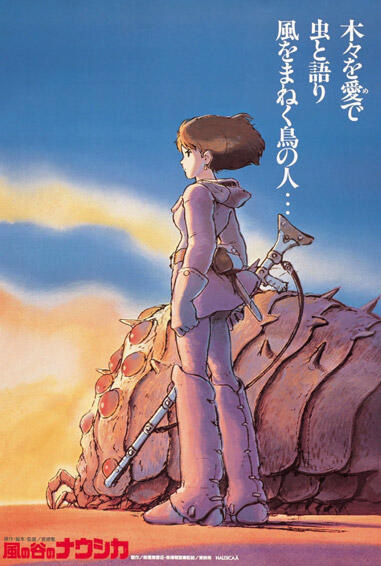

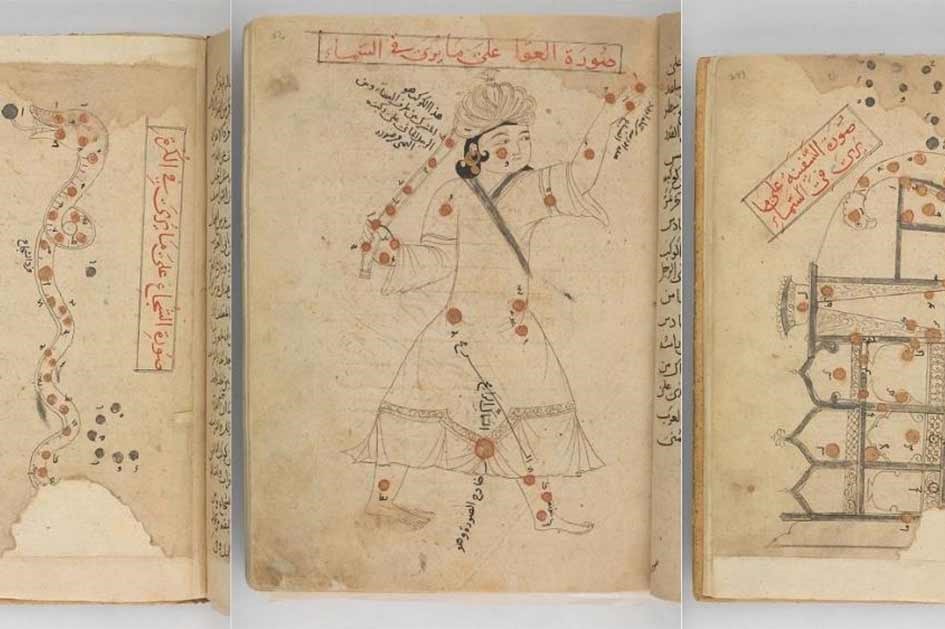

The “suwar al-kawakib” or the Book of Fixed Stars is a 10th century astronomical Arabic text, authored by the famed scholar Abd-al Rahman al-Sufi in the year 964 AD. It was produced by the powerful Greco-Arabic translation movement, which emanated in Baghdad and sought to translate secular Greek classical texts and the works of Hellenistic scholars into Arabic.

The syncretic traditions of Western Asia were once culturally aligned owing to the dominance of Islam over the medieval world and the access to the Silk Road . Now, this has prompted Uzbekistan to present the “first true-to-the-original facsimile copy of the manuscript of Images of the Fixed Stars” reports Euronews.

Uzbekistan was at the heart of the ancient Silk Road. Its central location in the Eurasian trans-continent allowed it to become one of the first civilizations to develop and grow.

With the goal of preserving this rich cultural heritage, Project: Cultural Legacy of Uzbekistan in the World Collections was launched to identify, catalogue, and showcase all art objects reflecting the country’s cultural heritage scattered around the world. 350 scientists from all over the world were brought together at this keynote event of Uzbekistan’s Cultural Heritage Week.

The conversion of this work from a manuscript to a book was commissioned by the Timurid Sultan and Dynast, Ulugh Beg, in the late 14th and early 15th centuries. He was a renowned astronomer and mathematician, having done great work in the field of trigonometry and spherical geometry, and was a patron of the arts and other intellectual activities.

He would go on to commission and build the great Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand. This is, to this day, one of the finest observatories of its kind in the world.

Abd-al Rahman al-Sufi made his observations from Isfahan in Iran, dedicating the Book of Fixed Stars to Adud al-Dawla, his patron and a Buyid Emir. Al-Sufi was responsible for innovations in charting the stars, updating Ptolemy’s stellar longitudes from 137 AD to 964 AD by adding 12 degrees and 42 minutes on Ptolemy’s longitudinal values to allow for precision.

For this, he used the production of dual illustrations for each of Ptolemy’s constellations. One illustration was portrayed on a celestial globe, while the other was viewed directly in the night sky.

This book was not his only contribution to the field of astronomy and science. He contributed to the building of an important observatory in the city of Shiraz, and played a role in the design of many astronomical instruments such as astrolabes and celestial globes.

He identified more than 100 new stars, along with the first known descriptions and illustrations of the Andromeda galaxy, and the first recorded mention of the Large Magellanic Cloud, reports Paudal. He was able to improve on a lot of Ptolemy’s observations through empirical data and conclusions, and his influence in astronomy reverberated right up to the 19th century.

The book is often hailed as a masterpiece of Central Asian art. It can also be taken as proof that the later Renaissance movement in Europe was in part a by-product of the cultural exchange that had emerged with transcontinental trade and exchange with Asia, particularly those regions connected to the ancient Silk Route.

It contains 74 tiny and fascinating miniatures of constellations, executed with exquisite panache and style. And it is one of the oldest surviving treatises of a time when illustrated manuscripts were coming into focus.

Scientifically, it combines the principles of ancient Arab astronomy, with knowledge of the stars transmitted by the Greeks. Abd-al Rahman al-Sufi took Ptolemy’s entire catalogue and merged them with the ones mentioned in Arabic literature.

The effect of this resonates right into the modern world. So much so, that Uzbekistan today plans to tap into culturally and scientifically rich historical works like this one and help spur advanced scientific technologies and discoveries, to help preserve historical exhibits and manuscripts.

A detailed ASMR ear exam, otoscope examining, latex glove touching and softly spoken inspecting deep inside the ear. ASMR medical videos are for sleepy entertainment purposes only and should not be taken as actual medical advice.