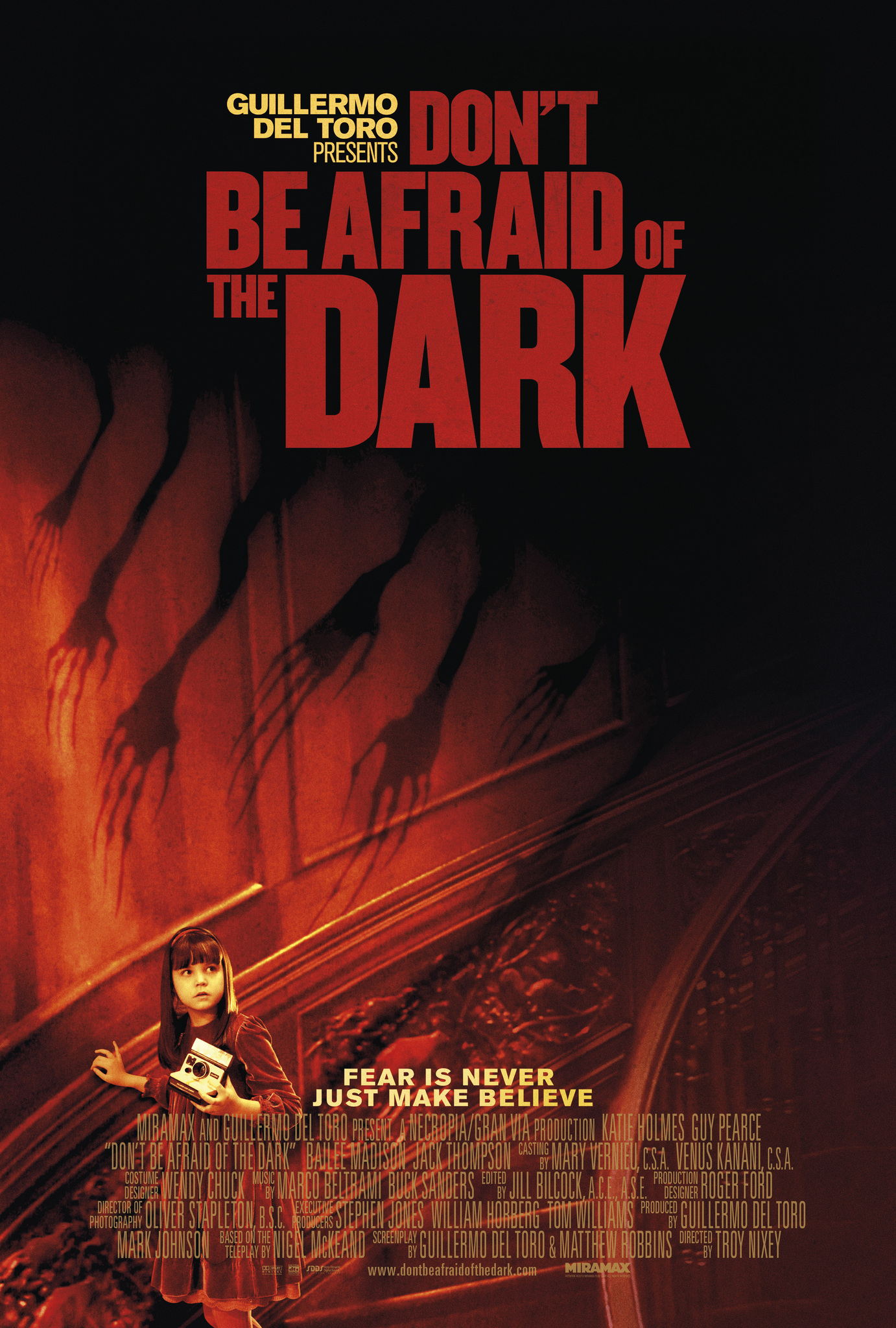

Serbian born Nikola Tesla was one of the greatest scientists of all times. His numerous inventions changed the world. He is best known for designing our modern AC electrical system. Have you ever plugged something into a wall outlet? You can thank Mr. Tesla for that. And that’s not even close to all of it.

Tesla obtained about 300 patents, covering many topics. At least 4 of them found their way into the first radio. Even so, his talents went beyond electrical engineering. Covering mechanics, chemistry, physics, his interests were vast. Many of his inventions are finding new uses even today.

His brilliant mind earned him fame and respect around the world. He was friends with Mark Twain, the famous writer. Even Albert Einstein thought Tesla was the smartest man alive. Sadly, he never found long term financial success. Despite this, he led an interesting life and accomplished many things.

Early life

Nikola Tesla was born July 10th, 1856 in Smiljan, Croatia. His father was an Orthodox priest, and his mother ran the family’s farm. Nikola was the fourth of five children. He had three sisters and an older brother. Dane, his brother, was killed in a horse-riding accident. Tesla was five years old when it happened.

In 1861, Nikola began primary school in Smiljan. Soon after, the Tesla family moved. In 1862, he continued his education in Gospic. His father worked as a priest at the local parish. At age 9, Nikola moved to Karlovac. He attended high school at the Higher Real Gymnasium. It is here he became interested in electricity. He later wrote that his physics professor inspired him to “know more of this wonderful force”.

Tesla graduated in 1873. He returned to Smiljan only to contract cholera. He became ill for nine months and was near death. His father promised to send him to the best engineering school once he recovered.

Education

Tesla began college at Austrian Polytechnic in Graz in 1875. For his first 2 years, he performed very well. He achieved the highest grades possible and had perfect attendance. He was a fast learner and proved to be far ahead of his peers. Tesla worked long hours, to the point that his professors became concerned.

During Tesla’s third year, he became addicted to gambling. He gambled all of his tuition money and had to drop out of school. Upset that he hadn’t finished school, he went off on his own. He moved to Maribor and worked as a draftsman. In 1879, the police returned him to his home in Gospic, because he didn’t have a residence permit. His father died the same year.

In 1880, Tesla left for Prague to study at Charles-Ferdinand University. Unfortunately, he arrived late and could not enroll. He did audit some classes. But this was the last attempt he made to complete his education. Soon after, Tesla began working at the Continental Edison Company.

Tesla vs Edison

In 1884, Tesla went to New York to work for Thomas Edison. He worked there for a year and impressed Edison with his knowledge and skills. Tesla eventually improved Edison’s DC dynamo. He hoped to sell it to Edison, but he turned him down. Tesla soon quit and began his own company.

The Tesla Electric Light Company failed almost as soon as it started. As a backup, he got a job digging ditches. Eventually, he found financial support for some of his AC research. After not much time, he was granted over 30 patents.

His work gained him attention. A short time later, he was invited to speak at the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. It was here that he met George Westinghouse. Westinghouse was an inventor and Edison’s biggest competition.

He hired Tesla and gave him his own lab. Together they developed the AC tech that would replace Edison’s DC power system. He worked here for a few years before going off on his own once again.

Laboratories

From 1889 to 1902, Tesla worked out of several shops around New York. He had licensed enough patents that he could fund his own research. During this time period, he had his most important discoveries.

Among them, the radio, fluorescent light bulbs, steam engines. Over the years Tesla became involved in many projects. The list of inventions is too long for this page! One that stands out, the Tesla coil. One of our personal favorites.

In the morning hours of March 13 of 1895, Tesla’s S. Fifth Ave laboratory caught on fire. Years’ worth of research was destroyed. This included notes, models, demonstrations. Tesla was devastated.

From the 1890s through 1906, Tesla spent most of his time researching wireless power. In 1899, he set up a laboratory in Colorado springs. Its purpose was to study the conductive properties of low-pressure air. The rural location offered him space, unlike his cramped labs in New York. Here he experimented with radio transmission, wireless power, and artificial lightning bolts.

Wardenclyffe Tower

In 1901, Tesla set out on an ambitious project in Shoreham, NY. The Wardenclyffe tower aimed to provide both wireless power and communication to the globe. For a time he made quite a bit of progress. Later that year, Marconi made a record-breaking long-range transmission. This in effect complicated Tesla’s efforts.

Investors were putting their money into Marconi’s radio. Meanwhile, Wardenclyffe’s financial troubles mounted. Eventually, the project came to a halt in 1906. He lost the property and the tower was ultimately demolished.

Since that time, the old lab has been purchased by the Tesla Science Center. The goal is to restore it to its original condition. While progress has been made, there is still a long way to go!

Mark Twain and Nikola Tesla

Tesla claims that Mark Twain‘s writings saved his life. He became familiar with his books when he was younger and sick with cholera. Later on, the two met and Tesla got to tell Twain about his recovery. The two became fast friends. This was in part because Mark Twain was fascinated with technology himself.

He had been known to invest in inventions. Over the years, Twain visited Tesla’s lab several times. He even participated in some experiments. In one notable experiment, Tesla was able to cure his constipation. By sitting on a vibrating plate, it didn’t take long before Twain had to run for the bathroom.

What did Nikola Tesla Invent

Nikola Tesla had a long list of inventions. While there are too many to name, here are some of our favorites.

Tesla vs Einstein

Tesla was not a fan of Einstein. In a 1935 New York Times article, He said the following:

“The theory wraps all these errors and fallacies and clothes them in magnificent mathematical garb which fascinates, dazzles and makes people blind to the underlying errors. The theory is like a beggar clothed in purple whom ignorant people take for a king. Its exponents are very brilliant men, but they are metaphysicists rather than scientists. Not a single one of the relativity propositions has been proved.”

Tesla’s dislike for Einstein’s theory even led him to write poetry. Amongst the many lines, Tesla scoffed at the idea that “energy and matter are transmutable”. Presumably referring to E=MC^2.

Einstein, on the other hand, seemed to hold Tesla in high regard. When asked, “what is it like being the smartest person in the world?”, He responded, “You’d have to ask Nikola Tesla”.

Aliens

During Tesla’s Colorado Springs experiments, he noticed something unusual. He was tracking lightning storms, and his equipment received some odd transmissions. After ruling out earthly causes, he concluded they must be from space.

Tesla was so sure of his discovery, he wrote “Brethren! We have a message from another world, unknown and remote. It reads: one… two… three…”.

In 1966, scientists replicated Tesla’s experiments. They discovered that he did in fact receive signals. Sadly, they were caused by the moon passing through Jupiter’s magnetic field.

Death Ray

Few things are more mad science than directed energy weapons. Tesla claimed to have invented just that.

He explained “this invention of mine does not contemplate the use of any so-called ‘death rays’. Rays are not applicable because they cannot be produced in requisite quantities and diminish rapidly in intensity with distance. All the energy of New York City (approximately two million horsepower) transformed into rays and projected twenty miles, could not kill a human being, because, according to a well-known law of physics, it would disperse to such an extent as to be ineffectual. My apparatus projects particles that may be relatively large or of microscopic dimensions, enabling us to convey to a small area at a great distance trillions of times more energy than is possible with rays of any kind. Many thousands of horsepower can thus be transmitted by a stream thinner than a hair so that nothing can resist.”

While no death ray was constructed, the plans were used to pay an overdue hotel bill.

Later Years and Death

Tesla’s final years were spent in poverty. He lived alone in cheap hotels. He continued working on new ideas though his health was fading. As time went on he is said to have developed friendships with pigeons.

Tesla died on January 7, 1943. His age at death was 86 years. Later that year, the US Supreme Court struck down some of Marconi’s patents. This in effect credited Tesla as the inventor of the radio. To this day, his AC system still powers the whole world.

“In this land, the undead are corralled and led to the North, where they are locked away to await the end of the world.” This was the line that gripped me when I started up Dark Souls for the first time in late 2011. It’s a line I’ve found myself returning to again and again when I try to conjure up the particular quality of Dark Souls’ world that makes it so enticing. Not that enough thought and words haven’t been expended on the series already: over its six year history, which if From Software are to believed marks both its beginning and end, the writing, debates and other games the series can have said to inspired makes for an impressive volume of work. Even the game’s architecture, my subject specialty, feels like it has been dissected from many angles, its gothic arches and vaults often connected to many different histories of horror and the sublime. However, even with all this activity around the series, it feels necessary, with the final DLC of the final game The Ringed City having passed and settled into its place, to write an obituary of sorts for its particular collection of spaces and structures, at least before the predictable resurrection that the game’s financial success and avid fan base will surely trigger.

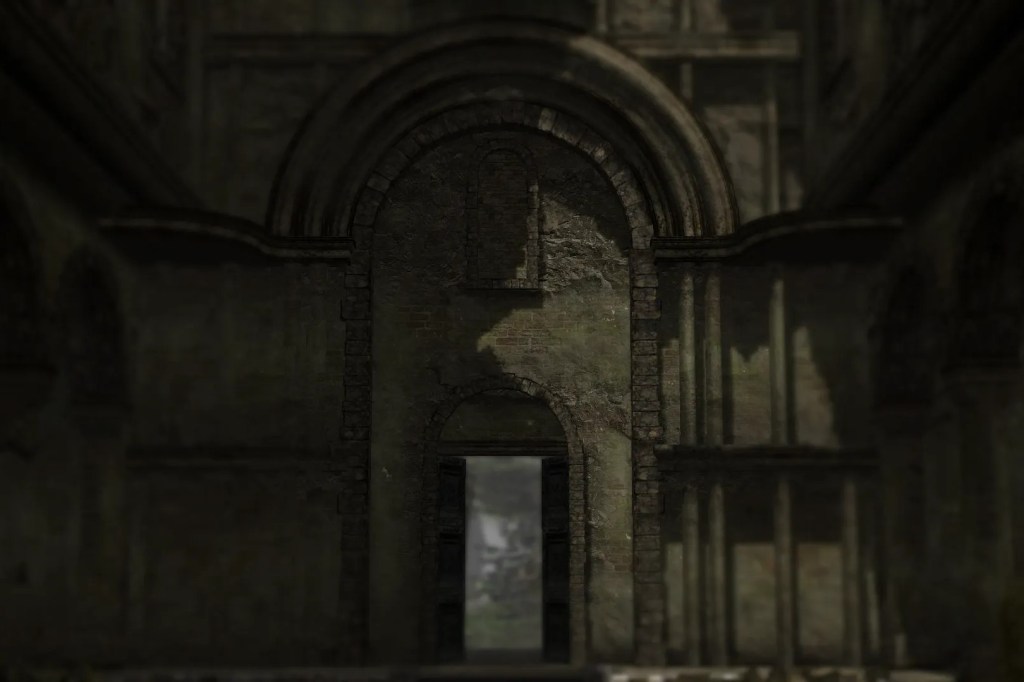

The reason I say obituary is because for me, the depiction of architecture in Dark Souls orbits around one central theme: death. Let’s go back to that first line: its poetry lies in the idea of the undead not as rampaging monsters, or mystical beings, but as the cursed; those who have been denied death. Without the comfort of inevitable death, there is only one end that awaits them: the end of all things. And what really makes that line stick in my mind is how it combines this erasure of death with a distinct sense of space. The reference to a kingdom or a “land”, the icy, distant presence of the word “North” and the hollow prisons suggested by the phrase “locked away” give an overriding sense of architecture, and its function as a prison, a refuge, or a container for the dead. This line points to the central architectural image of the series: a crumbling edifice in which the deathless wander, meaning sapped by time from both the undead’s decaying bodies and the stones that encase them.

This idea of architecture as a container for the dead has an ancient history. Howard Colvin, one of the great architectural historians pointed out that “architecture in Western Europe begins with tombs” pointing to the neolithic funereal monuments, hewn in rough stone, which have been part of our landscape for more than 12,000 years. However the connection is not only a historical one: Alfred Loos, one of the most influential theorists of Modern architecture, found something essential in the connection between architecture and death, writing “if we were to come across a mound in the woods, six foot long by three foot wide, with the soil piled up in a pyramid, a somber mood would come over us and a voice inside us would say, ‘There is someone buried here.’ That is architecture.”

Here Loos is referring to the ability or architecture to create and change space: a blank field, when filled with headstones, becomes charged with meaning, atmosphere and power. But he is also suggesting that the connection between death and architecture is not just one of pragmatism-that the dead have to be put somewhere, but is instead one of symbolism-the tomb as a structure is both a container of the dead, and an affirmation and symbol of life. It is a marker that its resident once lived. In this sense the tomb is perhaps the mirror twin of the room, a space designed to hold life, but that in its dead, empty, decaying form serves as a reminder of death. As the dying man in Vladimir Nabokov’s short story Terra Incognita realises in his final moments “the scenery of death” is little more than “a few pieces of realistic furniture and four walls.”

Yet in Dark Souls’ world these divisions between life and death have become lost, and so it follows too that the binary of tomb and room might be lost also. The spaces of the Dark Souls series are eternally caught in a state of undeath, between collapse and continuance. Every architectural space in the series seems to oscillate between the state of tomb and room. Take the new Londo ruins, for example, a series of hollow voids above a lake that is later to be revealed to be the container for countless corpses, concealed out of sight. Or the Undead Crypt in Dark Souls 2, a vast funerary complex of monumental tomb architecture that at its heart hides the lands ruler not in the form of a corpse, but as an immortal living being, pacing his own crypt as if it was his throne room, awaiting, like the undead of the first games asylum, the end of the world. Of course, in Dark Souls’ case, the end of the world has already arrived. The Ringed City DLC, which this year marked the end of the series in both a fictional and real sense, invited players to “journey to the world’s end,” to descend into the first and last city. In the game, when we approach the Ringed City itself, we see it circled by a vast stone wall, just like the wall that obscures the city of Anor Londo in the first Dark Souls. And looking on this vast walled city I was brought back once again to my first experiences with the series, experiences that might instruct another way of considering its architecture.

It’s no coincidence that my Dark Souls character is and always will be named Steerpike. As the antihero of Mervyn Peake’s incredible three volume gothic masterpiece, Gormenghast, his was the first name that came to mind when I set eyes on the vast rock wall of Anor Londo and the void below from the crumbling vantage point of Firelink Shrine. In Peake’s world, an impossibly vast castle plays host to scattered generations of royalty and their servants, all locked in senseless rituals that guide them like nomads amongst overgrown halls and abandoned apartments. In his books Peake casts architecture as a weighty burden, a physical realisation of tradition, ritual and history that its inhabitants must try, and fail, to maintain and make sense of. The castle of Gormenghast is a vast undead corpse, returning to nature. Not a corpse of a single human however, but the corpse of an entire civilisation falling into ruin. Take Peake’s first description of the castle itself: He talks of the “shadows of time-eaten buttresses, of broken and lofty turrets” but perhaps the most striking feature is the way he describes the vast central “Tower of Flints” as rising “like a mutilated finger from amongst the fists of knuckled masonry and pointed blasphemously at heaven. At night the owls made of it an echoing throat; by day it stood voiceless and cast its long shadow.” This anthropomorphic description isn’t trying to suggest that Gormenghast might be a character in the novel, instead it is presenting it as a body; a voiceless, mutilated, blasphemous body. A body who must await the end of the world in order to truly die.

In evoking the connection of Dark Soul’s architecture to Gormenghast, the Ringed City suggests to me that the spaces of Dark Souls too could be thought of it the same way. They are perhaps the mirror image, not of the tomb or room, but of the bodies they contain. Like the series’ “hollows” a profoundly architectural name for the undead, the architecture of the Dark Souls’ series is, more than a container for walking corpses, and is instead a withering, putrefying, deathless corpse in itself. Its spaces, the cathedrals, castles, caves, sewers, fortifications and forest huts of Dark Souls and its sequels are hollow bodies, locked in processes of organic decay. A descent through the Ringed City only seems to strengthen this idea: it is a structure which at its highest point is drained of color, dry and calcified, but as you descend becomes fetid, waterlogged, sinking into its own fluids. At its base, it is infested with insects and parasites, its buildings pointing haphazardly up out of a congealed swamp. This imagery is something that can be traced through the series: the lowest point of the original game is the Ash Lake, a vast interior filled with branching structures like the interior of a set of calcified lungs, while the depths of Dark Souls 2 hide the Black Gulch, home of The Rotten, a literal living structure of undead corpses. Even when we return to Anor Londo Dark Souls 3, we find it decaying into a putrefied, black murk, as if it was not made of steel and stone, but some organic material that mirrors their properties.

And yet, whether we see the architecture of the Dark Souls series through the lens of both tomb and room, or as a vast decaying corpse, there is a contradiction we must accept. The spaces of Dark Souls, from its cathedrals to its humble huts, are cursed to remain ruins forever. As virtual spaces, these seemingly shattered structures are in fact fashioned as ruins by From Software’s exceptionally talented artists, their collapse frozen in single frames of beautiful decay. They are ultimately without a past or a future. They will never give in to entropy, erosion and time, and be erased from the landscape, and neither can they possess a true golden past, a moment when they were total, complete, unbroken. They were built as ruins and as ruins they will stay, so that in a thousand years we might return to these spaces and find them as we left them, in collapse but never collapsing, gesturing towards an end of the world that has, improbably, both arrived and yet will never come.

In this video I wanted to talk about autistic masking and how to unmask. This video focuses on the following questions:

Many people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) learn to mask their autistic traits by copying neurotypicals, resisting their instincts, scripting, and overcompensating for perceived deficits. And in this video, I share my experience with that, how masking affected my mental health, and what I’ve been doing to unmask my autism.

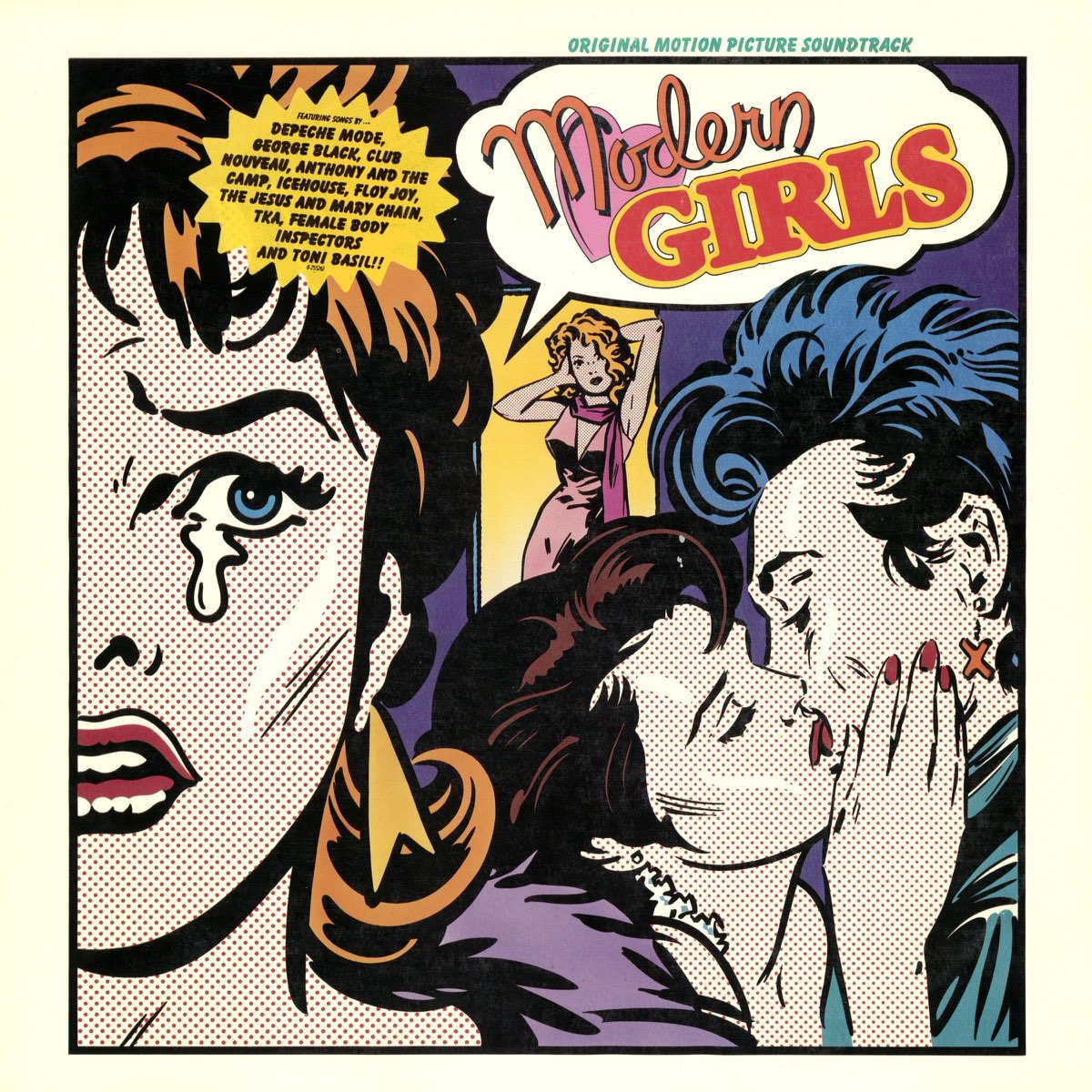

There were over 1,200 movies released in the U.S. during the 1980s. I figured out which one was the MOST 80s.

Emily Carr University of Art + Design (abbreviated as ECU) is a public art and design university located on Great Northern Way, in the False Creek Flats neighbourhood of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada.

Merging studio practice, research and critical theory in an interdisciplinary and collaborative environment, ECU encourages experimentation at the intersections of art, design, media and technology. According to the QS World University Rankings, ECU has ranked as the top university in Canada for art and design since 2019, and is currently ranked 24th in the world.

The university is a co-educational institution that operates four academic faculties: the Faculty of Culture + Community, the Ian Gillespie Faculty of Design + Dynamic Media, the Audain Faculty of Art, and the Jake Kerr Faculty of Graduate Studies. ECU also offers non-degree education via its Continuing Studies programs, Certificate programs and Teen Programs.

ECU is also home to the Libby Leshgold Gallery — a public art gallery dedicated to the presentation of contemporary art by practitioners ranging from emerging and marginalized artists to internationally celebrated makers. The Libby Leshgold Gallery serves a broad and varied community that includes the students, faculty and staff of the university, the arts community, the public of Greater Vancouver and visitors from around the world.

The institution is named for Canadian artist and writer Emily Carr, who was known for her Modernist and Post-Impressionist artworks.

Emily Carr is one of the oldest post-secondary institutions in British Columbia and the only one dedicated to professional education in the arts, media, and design.

Formally established as the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts in 1925, the school was renamed the Vancouver School of Art in 1933.

In 1978, ECU was designated a provincial institute and renamed the Emily Carr College of Art and Design in before moving to Granville Island in 1980. In 1995, it opened a second building on its Granville Island campus, at which time it was renamed the Emily Carr Institute of Art + Design. Around the same year, ECU was granted authority to offer its own undergraduate degrees (BFA and BDes) and honorary degrees (honorary Doctor of Letters (D.Litt.), Doctor of Laws (D.Laws), and Doctor of Technology (D.Technology).

The first graduate program was added in 2003 (MFA) and would later expand to include the Master of Applied Arts (MAA) in 2006, the Master of Digital Media (MDM) in 2007, and the Master of Design in 2013 (MDes). The MDM program was launched through the Centre for Digital Media, a campus consortium of four post-secondary institutions in British Columbia.

In 2017, ECU moved from its longtime home on Granville Island to a permanent, purpose-built campus on Great Northern Way. The new campus sits on a former industrial site within the False Creek Flats neighbourhood in East Vancouver. Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design’s arms, supporters, flag, and badge were registered with the Canadian Heraldic Authority on April 20, 2007. On April 28, 2008, the Provincial Government announced that it would amend the University Act at the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia and recognize Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design as a full university, which would be named Emily Carr University of Art + Design. The university began its operation under its current name on September 1, 2008.

The university’s campus is located within a four-storey 26,600 square metres (286,320 sq ft) building in the False Creek Flats neighbourhood of Vancouver. Designed by Diamond Schmitt Architects and completed by EllisDon in 2017, the building houses student commons spaces, galleries, exhibition spaces, studios and three lecture theatres. The exterior facade of the building has white metal panels and glass reminiscent of a blank canvas, as well as back-painted glass spandrel panels to evoke a sequence of colours and transitions. The building’s colour palette was selected by faculty members in honour of Canadian painter Emily Carr. In addition, several Indigenous design elements were incorporated into the design of the building.

The building forms a part of the larger Great Northern Way Campus, a 7.5 hectares (18.5 acres) multi-use property that is shared with four other post-secondary institutions through the Great Northern Way Trust. Emily Carr University, along with the British Columbia Institute of Technology, Simon Fraser University, and the University of British Columbia, are all equal shareholders in the trust. The Great Northern Way Campus also houses facilities used by the other three post-secondary institutions.