star trek. Thanks to AriesHeadFilms. They did a fine job, very creative. Check out their channel.

Yes, I know, this review is ridiculously late.

But … for fans of the first two Golden Sun games on the Game Boy Advance that have been looking forward to this anticipated, yet quietly-released Nintendo DS sequel, this review being late is a good thing.

You see, Golden Sun: Dark Dawn is a huge game. This is not a lazy, quickly put-together sequel to appease fans who have been clamoring for a new game in the series for years. This is a fully realized, super robust RPG that feels about as long as the first two Golden Sun games combined.

So, yeah. This review is late because the game took me a really long time to complete.

But was that long time (40+ hours!) spent playing a worthy follow-up to the cult-tastic previous games in the series? Or did I just waste a lot of great holiday gaming time on something ultimately disappointing?

At the conclusion of the last game in the Golden Sun series, The Lost Age, the heroes of the first two games activated the healing power of the Golden Sun, saving the world of Weyard from decay and certain destruction. (For non-fans of this series that decided to still click on this review you probably have no idea what I am talking about.)

While this would normally be a good thing, releasing the all-powerful, elemental-based force of Alchemy on the land completely changed the world: continents shifted, towns crumbled, and new monsters were born. While the heroes were praised by some for saving the world, others criticized them for releasing a force that may have never been meant to be released.

Golden Sun: Dark Dawn begins thirty years after this magnificent, yet cataclysmic event, as a new set of heroes sets out to investigate some mysterious happenings in the newly formed world.

In a clever twist, you take on the role of main character Matthew, son of the original game’s heroes Isaac and Jenna. In fact, the three characters in your party at the start of the game are all sons or daughters of the heroes from the first two games.

And this is something I have always loved and respected about the Golden Sun series. Instead of each game being a completely new story with completely new characters (like Final Fantasy), each game continues an epic story and involves similar characters and locations that all exist in the same overall world.

While some may think this would be boring — visiting the same places over and over again — I find it all very interesting. Following around a set of characters (and their offspring!) in an ever-changing world is fascinating. It helps the world feel alive, and makes running into old characters from previous games both surprising and exciting.

Upon starting Golden Sun: Dark Dawn, I was instantly a fan of the three main characters Matthew, Karis, and Tyrell, if only because I had got to know their parents so well in the previous two games.

But as I started playing the first two hours of Golden Sun: Dark Dawn, I was worried I wasn’t going to like the game.

And that made me sad.

The first two hours of Golden Sun: Dark Dawn is a lot of dialogue and a lot of battles.

And as much as I love the world of Golden Sun, the battle system is initially a little overwhelming and, frankly, a little boring.

Utilizing a turn-based system activated by (old school alert!) random battles, Golden Sun: Dark Dawn has you selecting from a large menu of options to battle a variety of monsters with various difficulty levels.

As traditional and familiar as this all sounds, the problem lies in the way the battles play out. While players can select from classic Attack, Defend, and Magic (in these games called “Psynergy”) choices, the main focus of the Golden Sun series lies in the Djinn, Pokemon-like creatures that can be called upon to perform special moves in battle.

Collected around the world either in random battles or by finding them in hidden places, the elemental-based Djinn have two functions. Each playable character in the game (of which there are more than you might think!) can carry up to nine Djinn at once, each having its own special skill — one may unleash a basic attack, one may heal the party, while others offer special bonuses that boost your strength or defense.

In battle, each Djinn can be activated from the menu. Once used, the Djinn puts its power into a “summon pool” (as I like to call it). Once this “summon pool” collects a certain amount of a specific elemental-type of Djinn, a massive creature can be summoned. And these creatures are what help you the most in almost every battle (eventually the Attack and Psynergy selections become almost completely underpowered).

And therein lies the problem. With so many options to choose from in battle, things don’t flow as smoothly as they should. Say you want to build up your “summon pool” enough to summon a massive dragon, and this dragon takes four Wind Djinns to call. Depending on what Djinns you collect in the field, all the Wind Djinns you have to use to summon this dragon could be completely useless (i.e. revive a party member … when no one is dead) and therefore basically amount to you wasting four turns in a row just to get those Djinn into your pool.

If all of this sounds confusing and kind of annoying, it is.

And the first two hours of Golden Sun: Dark Dawn doesn’t involve much more than dealing with this strange, not very exciting battle system (in between some pretty long cutscenes).

Because of all this I was a little turned off.

But, luckily, things turned around rather quickly.

Once you get used to the battle system — and start to collect more useful Djinn — the battles become pretty fun, and not nearly as tedious and slow.

And once you really start journeying around the world, you immediately realize that the battles become a secondary part of the game. The real focus of the game is exploring the world and solving some surprisingly clever puzzles.

Unlike most RPGs, Golden Sun: Dark Dawn puts a heavy emphasis on the exploring and puzzle-solving you do outside of battles. Instead of just walking around, occasionally talking to people and buying equipment between battles (don’t worry, you still do that stuff as well), the game tasks you with entering enormous, complicated dungeons filled with puzzles and traps straight out of the Zelda series.

Since all the Golden Sun games are based around elemental Psynergy, each character is equipped with different elemental powers that can be used in or outside of battle. In battle, these powers come across as generic spell attacks, but outside of battle they are so much more.

The “Growth” Earth-based power, for example, can grow vines and open up new paths when walking around the enormous and varied world of Weyard. “Move” can push giant blocks, while “Fireball” forms a massive fireball that can do many different things (from lighting torches to burning away the roots of trees).

Once you start exploring these dungeons, the game goes from a competent, if rather traditional RPG to one of the genre’s most engrossing and clever offerings. And as the lengthy adventure continues, the dungeons, Psynergy powers, and puzzles only get better and better, culminating in one of the best-designed and satisfying final dungeons I have ever played in any role-playing game. Great stuff!

So, I guess the moral of this review is to not judge the game based on the first couple of hours alone. Just keep in mind that it only gets better as the game goes on.

In addition to the remarkable puzzles, the game also looks and sounds fantastic. While a lot of “3D”games on the DS leave little to be desired, Golden Sun: Dark Dawn’s rich color palette and strong texture work make it one of the better-looking games on the Nintendo DS. I thought I would miss the classic 2D look of the original Game Boy Advance games, but after journeying through an increasingly gorgeous Weyard, I quickly forgot about the old games and was happy Camelot went in a new visual direction with Dark Dawn.

It is also worth mentioning that the summons in the game are not only out of control and over-the-top, they are absolutely breathtaking. I may go so far as to say the numerous different summon animations are some of the best (and most elaborate) I have ever seen in any RPG, even rivaling those seen in classics Final Fantasy VII and Final Fantasy VIII.

After some initial hesitations, I grew to love Golden Sun: Dark Dawn. The game is polished, well-designed, and, for fans of the series, surprisingly moving in parts. Camelot has finally seemed to perfect the slightly flawed Golden Sun design with Dark Dawn, easily making it the best of the series.

Golden Sun has a very cult-like following — since this review is so late, I am assuming all the fans of the series have already picked it up.

But for the people who still have not got around to purchasing it, there is no need to hesitate. With the 3DS set to take over the handheld world in a few months, Golden Sun: Dark Dawn may just be the last great RPG for the legendary Nintendo DS.

First of all, I will give Moore credit for making certain ideas mainstream (what other remotely progressive or even politically challenging material are you going to see at a multiplex cinema?), and for his interviews with the working people of the United States and coverage of their struggles, which helped to energize me a bit. On the flipside, it must be stated that his new film “Capitalism: A Love Story” is not a condemnation of capitalism. It is a “middle class” lament. It is an Obama promotional video. It is periodic social-democratic indulgence to release latent tensions that threaten to burst the restraining tethers of bourgeois society.

As usual, I don’t care for Mike’s theatrics. In general, I think that “street theatre” is an impotent mode of political agitation, and his clown tactics rarely yield constructive results. On the other hand, I recognize that he has to maintain an element of mass appeal, so he packages his film as a comedic documentary, as opposed to the conventional stuff on PBS.

The show begins, as do most Moore films, with a montage of old media clips and clips from his own childhood home films, showing a flurry of 50’s American nuclear families enjoying themselves in decadence (i.e. waterskiing) and working in industry, representing American capitalism in it’s consumeristic, not-yet-moribund state during the early Cold War.

So, early in the film it becomes clear that by no means is Moore criticizing capitalism. On the contrary, he exalts it to the high heavens, and waxes nostalgic about it during his youth. He shows this montage of clips representing how good capitalism was at one point, all with only the most minimal references to imperialism. How can anyone do a serious documentary about capitalism by focusing on the one country that is the recipient of all of the finished goods, wealth and flow of capital?

He states, without irony, that the US auto-manufacturing sector rose to prominence because of the destruction of the manufacturing sectors of both Germany and Japan (including horrific crimes against humanity like the attacks on civilian population centers at Dresden, Hiroshima and Nagasaki). What Moore is noticeably quieter about is how these defeated countries were then turned into proxies of the United States and markets for their exported goods. He does point out that the United States rewrote the constitutions of the defeated Axis powers, but paints this as a very positive thing rather than imperialism.

So, it is not capitalism that Moore is criticizing; it is the post-Cold War polarization in wealth. It is the decimation of the “middle class,” and their subsequent loss of socio-economic privileges.

Moore then goes on to feature a lot of stuff about “What does Christianity think of capitalism?” This may ruffle the feathers of the more materialist and anti-theist, but I actually don’t criticize Moore for this approach. The United States is a deeply religious country, so he is finding his way to make some ideas acceptable to the existing level of consciousness of the people (I myself began as a Christian Marxist, despite the obvious contradiction). Scoffing at the religious sentiments of millions of American workers negates them, so Moore instead doesn’t directly tell them “abandon all ye Gods!” when he is (supposedly) targeting capitalism.

The only issue with this is, from a materialist point of view, it becomes pure bourgeois metaphysics. Moore literally asks the Catholic priests and Bishops “is capitalism a sin?” By doing this, he takes the root of the problem with capitalism out of the material world of tangibility, and places it onto the no-no list of divine preferences.

So now, the crimes of capitalism are put into the same basket as worshipping idols and unwed intercourse—there are no tangible negative effects from doing these things, but the faith considers them morally repugnant.

Moore could have settled for a compromise that showed Christian attitudes towards socialism, such as Acts 2:42 to 2:45, which state, “42 And they continued steadfastly in the apostles’ doctrine and fellowship, and in breaking of bread, and in prayers. 43 Everyone was filled with awe, and many wonders and miraculous signs were done by the apostles. 44 And all that believed were together, and had all things in common; 45 And sold their possessions and goods, and parted them to all men, as every man had need.” He could’ve then contrasted these with attitudes towards capitalism: “…I tell you the truth, it is hard for a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven. Again I tell you, it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God.” –Jesus Christ, Matthew 19:23-19:24. But he did not attribute the ills of capitalism to moralism and the displeasure of a deity. This would have been a preferable stance.

Moore, at one point, looks at the rash of home foreclosures in the states and says, “This is capitalism.” Well yeah, but not in its entirety. That is only one of the symptoms, and it becomes meaningless because Moore doesn’t raise issues with the fact that even during the golden prosperity of the Cold War (built on the backs of rampant military expansion) workers were still confined to exploitive relations. So, ultimately, again it is not capitalism that Moore is raising issue with, but rather the disenfranchisement and polarization of the “middle class” in the face of monopoly capital. At no point does Moore draw the conclusion that capitalism is inherently exploitive, despite all of his “capitalism is evil” rhetoric.

At one point in the film, a couple that is being evicted in Peoria releases a pearl of wisdom. The husband says something along the lines of “there needs to be some kind of uprising of the have-nots against the haves.” If only Moore himself had taken this to its logical conclusion. Throughout the film, Mike endorses “socialism,” but of course by “socialism” he means Sweden, not the USSR. He literally drools over the “socialism” of Germany where Unionized workers have a say in choosing their board of directors (and of course, at the end of the day, they don’t own the factory that they are working in), and gives a cheer for the New Deal policies of FDR.

So here, “socialism = New Deal.” “Socialism = capitalism with concessions.” No worker control, no expropriations from the bourgeoisie, no abolition of private property, no abolition of class. Pension, pseudo-nationalized health care, giving the Unions a say in management… this is called “socialism.”

He points out how historically the National Guard under Roosevelt was used to protect striking workers in Michigan. He ignores all of the other times when the National Guard (or other state forces of the US) was used to put down strikes, which has usually included wholesale murder of strikers and union organizers. He unloads all of the crimes of American capitalism onto Ronald Reagan and George Bush Jr., and absolves Jimmy Carter and FDR in the act. Bless their heart, they were just trying to help (at least he does shy away from Clinton nostalgia though).

And then, in the midst of all of the legitimate human misery portrayed in his film by the American people, a messiah emerges. That’s right—his name was Barrack Obama. The movie starts to wind down on a high note. Obama was elected, and this signaled the dawn of a “New America.” How so? Who knows?

Obama has so far continued the wars of aggression in the Middle East, voiced the same unconditional support for Israeli apartheid, clings to the same founding myths of the United States, still maintains the same capitalist system in place (in fact, he kept them on life support with public funds), and America is hardly “post-racial” as exemplified by the case of Professor Gates among others. So the film winds down as an Obama campaign ad. Things were horrible in the United States, but then Obama came, parted the Red Sea, and lead his people out of bondage in Egypt. Roll credits.

While to his credit, Moore features the fantastic action of the Republic Windows workers, who occupied their factory in lieu of unpaid wages, he ends their story on the high note that they got their wages and the struggle ended peacefully. So, here Moore reinforces the moral of his story: if the workers and oppressed people fight tooth and nail, the capitalists will part with some of their ill-gotten gains. Don’t really challenge capitalism, just take your bribe and go home.

He also portrays some worker -owned and operated industries in the US, like the reclaimed industries in Argentina portrayed in Naomi Klein’s documentary The Take, but he portrays this syndicalism as being a new stage of capitalism—collective capitalism as opposed to the top down pyramid model. Now, of course factory syndicalism in the US becomes meaningless because the overwhelming majority of the American economy is still in privately-owned hands with a division between ownership and labor, the United States ruling class still exists and thrives, and political power rests in their hands.

Essentially, all that Mike is advocating is Argentinean-style syndicalism in the workplace, Swedish-style social programs in society, and Jeffersonian democracy for all! Together, these elements do not equal socialism.

The whole thing ends with, of all songs, the Internationale (Billy Bragg lyrics) sung over the credits. I can’t tell if this was admirable or vulgar. Considering the pace and content of the rest of the film, about shrinking “middle class” privilege where “socialism = concessions from the bourgeois state,” this appropriation of the battle hymn of all humanity striving for emancipation seems like so much tasteless and degrading appropriation of socialist iconography as “revolutionary chic.” At least they didn’t defile the GOOD version of the song.

From start to finish, as usual, Moore plays the loyal opposition to the state wrapped in “radical” rhetoric. While this has succeeded in ruffling the feathers of the overt reactionaries like the National Post in my country, which featured a front-page article where they photoshopped Moore’s trademark glasses and ball cap onto Karl Marx, it boils down to same-old-same-old. Any condemnations of the still-ongoing wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Somalia and Haiti are absent from the film. Why condemn them? Just make sure that the American working class gets their cut of the plunder, because that is what “socialism” is, at least according to Moore.

In the end, it becomes just another band-aid on the growing cracks in a dam that is about to burst. Just as the bourgeois economists of the recession declared “We Are All Socialists Now,” and defiled the legacy of working class emancipation by linking it to their own fascistic self-serving bail out, Michael Moore declares that workers’ need to fight for their right to more concessions.

Over all, Mike’s “middle class” woes become tiresome. The working class doesn’t need concessions, nor should they aspire to a relatively less exploited position as the “middle class” beneath bourgeoisie. If anything useful can be taken from this film, it is the knowledge that no problems have been solved in the United States, and the conditions that give rise to revolution have not been alleviated at all. If anything, the situation is more dire.

Nobody rose so high in scientific achievement as Oppenheimer and fell like Icarus. He was the most important person in the development of the atomic bomb. He was falsely accused of spying for the Russians. He was described as an ambitious, insecure genius with naivety, determination as well as being stoical, (Bird& Sherwin, 2009).

He was close to his mother, and he said, ‘she loved me too much’. He was devastated when she died of leukemia. He had a pathologically negative relationship with his father. As a child, he was fascinated with ‘blocks’, and ‘rock specimens’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He was a lonely ‘unhappy’ child who ‘didn’t fit in’ and was often ‘incommunicado emotionally’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He was very eccentric.

He was an extreme intellectual and liked to work on his own on math problems. He was rigid, controlling and very dominating. He knew he was different from others. He was often tactless and unemphatic. Children particularly found it difficult to relate to him. He was an abstract thinker. He wrote about himself in the third person, which is typical of persons with autism. Unlike most people with autism, he had wide interests in poetry, language and literature. He loved walking, which is very common in persons with autism. Later he said, ‘he had very little sensitiveness to human beings, and very little humility before the realities of the world’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). Lilienthal described the ‘contradictions between opposites, a brilliant mind and his awkward personality… he did not know how to deal with people, his children especially’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). His daughter, Toni was a linguist but also shy like Robert. Toni hanged herself in 1977. His son, Peter, kept a low profile after Robert’s death and worked as a ‘contractor and carpenter’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009).

He used ‘florid language’ and often exaggerated. ‘His physics papers were unusually brief to the point of being cursory’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). This is a feature of autism. In lectures, he used to mumble in a soft, almost inaudible voice and would ‘stutter his oddly lilting hum that sounded like ‘nim-nim-nim’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He could terrorize ‘his students with sarcasm and be very cruel in his remarks’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He was charismatic and could mesmerize people with the power of his rhetoric. When Lilienthal, not a scientist, first met him he noted ‘huge’ sounds between sentences or phrases as he paced the room, looking at the floor – a mannerism quite strange’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009).

He suffered many depressive episodes. In a fit of jealousy, he left a poisoned apple on a friend’s desk. Nothing happened to the friend. Nevertheless, he was sent to a psychiatrist and later to a psychoanalyst who diagnosed him with schizophrenia. He never did have schizophrenia. He also felt like ‘bumping’ himself off, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). Once he tried to choke a friend. He was hyperkinetic and his pace was ‘frantic’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He interrupted a lot in groups, that is academic seminars which many people found intolerable.

He said, ‘I need physics more than friends’ and a colleague also said that ‘the longer I was acquainted with him, the less I knew him’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). This is often said about people with autism. A post-graduate student Harold Cherniss stated, ‘he didn’t quite know how to make friends’, (Bird & Sherwin,2009). He was often seen as mysterious, which is not uncommon in persons with high IQ and high functioning autism. In personal relationships, it was up to other people to take the initiative. Oppenheimer said, ‘I’m not an attached kind of person’. When his daughter was born he said, ‘I can’t love her’, and asked a friend if they would adopt her, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). In terms of relationships with women, he began mixing with a woman called Jean Tatlock. This broke up. She later completed suicide. He had a relationship with Kitty Harrison who became his wife. From his point of view, this was a rather masochistic relationship, and she was alcoholic. He had one very dangerous relationship with Haakon Chevalier, who asked him to spy for the Russians. He said this was treason. Nevertheless, when he told his boss about this later, he covered up for a friend and told a lie which got him into major trouble later on. He was a fellow traveler with communists but never joined the party and it was because he became concerned with poverty in America. He himself had never suffered poverty and came from an affluent background. Oppenheimer could be ‘caustic’, and ‘brusque’, and a colleague, Neddermeyer, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009) stated that Oppenheimer could ‘cut you cold and humiliate you right down to the ground’. He antagonized people a great deal and was often ‘impatient and candid to the point of rudeness’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He didn’t realize the full danger of Hoover from the FBI going after him. He was framed in a ‘Kangaroo Court’, who withdrew his security clearance. He could have simply resigned and saved himself all the trouble.

He used to make stereotyped movements with his hands. He walked with ‘a peculiar walk with his feet turned out at a severe angle’ and was ‘clumsy’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He was ‘impractical’ and ‘walked about with scuffled shoes and a funny hat’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009).

He was often tactless, and he was ´incapable of tolerating banalities´, and Professor Percy Bridgeman notes that he was a, ´quick on the trigger intellectual´, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He had a sense of humour, as persons with autism often have, (Lyons & Fitzgerald, 2004). He could also make callous and deeply wounding comments to people. He was a fussy eater. According to his brother, Frank, he divided the world into people who were worth, ´his time, and those who were not´, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He was a linguist. He also had identity diffusion and an immature personality. He often showed effortless superiority. He was novelty-seeking and a sensation-seeker. He was impatient with mathematical calculations. He was always trying to understand himself and his identity diffusion. His students began to copy his ´quirks and eccentricities´, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). The same happened with Ludwig Wittgenstein (Fitzgerald, 2000).

He had an interest in mysticism. At a party a fellow guest, John Washburns said of him, ‘never since the Greek tragedies has there been heard the unrelieved pomposity of Robert Oppenheimer’, (Bird & Sherwin,2009). He was described as, ´argumentative, sharp, pedantic’ and showed ‘political naivete’, (Bird &Sherwin, 2009). He was regarded by colleagues as being, ‘sort of nuts’ and eccentric as well as being an ‘awkward, scientific prodigy’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He had ‘a lack of interest in mundane affairs’, (Bird& Sherwin, 2009). According to John Manly, after Los Alamos he was noted to be more, ´arrogant´, and a ‘smart aleck’, who did not suffer fools gladly’, and still he was ‘very naive’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He loved the adulation after Los Alamos. A colleague, Freeman Dyson noted that, ´restlessness drove him to this supreme achievement, the fulfillment of the mission of Los Alamos without pause for rest or reflection’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). A colleague stated that he had a ´difficult temperament and poor judgement’, (Bird& Sherwin, 2009). He became more megalomaniacal after the war and felt it was his duty to prevent the world from nuclear destruction. President Truman called him after the war, a ´cry-baby scientist´, when he said to Truman wringing his hands, ‘I feel I have blood on my hands’ (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). This was an extraordinarily naive and immature way to talk to the President of the United States. He had an autistic superego, and this was seen, particularly post-Los Alamos. A colleague said, ´he thinks he is God´, and had a ‘priestly style’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). Nevertheless, there was a perverse element to Oppenheimer, and he loved, ‘to have people at the institute, (where he worked), quarrel with each other’, (Bird & Sherwin,2009). He showed pathological control. He often showed ‘fierce arrogance’ and made ‘biting comments’, while he was ’emotionally detached’, and an extraordinarily ‘private person’ who was ‘not given to showing his feelings’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He had identity diffusion which goes with autism and didn’t know quite who he was. According to Isidor Rabi, who knew him well he was often condescending, humiliating and had narcissistic contempt for Lewis Strauss in public, which led to Strauss destroying him. A colleague, Marvin Goldberger, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009), said he was an ‘extraordinarily arrogant, difficult person to be with. He was caustic and patronizing’. In terms of narcissistic personality disorder, (APA, 2013), he did achieve a massive amount, an almost unlimited success at Los Alamos, unlimited power and brilliance and was unique. This was all true, but he also showed pathological narcissism in ordinary interactions outside of Los Alamos. His wife felt that he had ‘no sense of fun and play’ and was ‘maddingly aloof and detached’ and lived life as an introvert, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). Nevertheless, he did mature somewhat in later life, and he knew that ‘some of his most depressing mistakes were due to his vanity’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). He finally had insight, but it was too late. He was narcissistically destroyed by the investigation. During all of his life however, he had been somebody who ‘loved controversy’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). Because of his narcissistic problems, he had a ‘talent for self-dramatization’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009).

He became head of the atomic programme to make the bomb. He did it brilliantly and probably no other man could have done it in the short time available. The reason General Groves chose him was because of his’overwinning ambition’, (Bird & Sherwin, 2009). Only such a man could develop the bomb in the time available. He was wrong to go against the H bomb which Russia later developed as well. This was Edward Teller’s pet project, and it was Teller who finally destroyed Oppenheimer by saying that he would prefer if the nuclear programme was in someone else’s hands, to Oppenheimer. Strauss (Bird & Sherwin, 2009) noted his ‘omniscience’. He had piercing eyes, often seen in persons with autism.

Oppenheimer was probably the most influential scientist of the twentieth century with the development of the atomic bomb. He was naive, had poor social skills, a penetrating gaze, some stereotyped movements and narcissism. All of this fitted with autism.

Pre-Rendered backgrounds have always been one of my favorite graphical styles, largely in part due to how effectively they were utilized on the PS1. In this video I discuss what it is exactly that makes these backgrounds so special, timeless and magical.

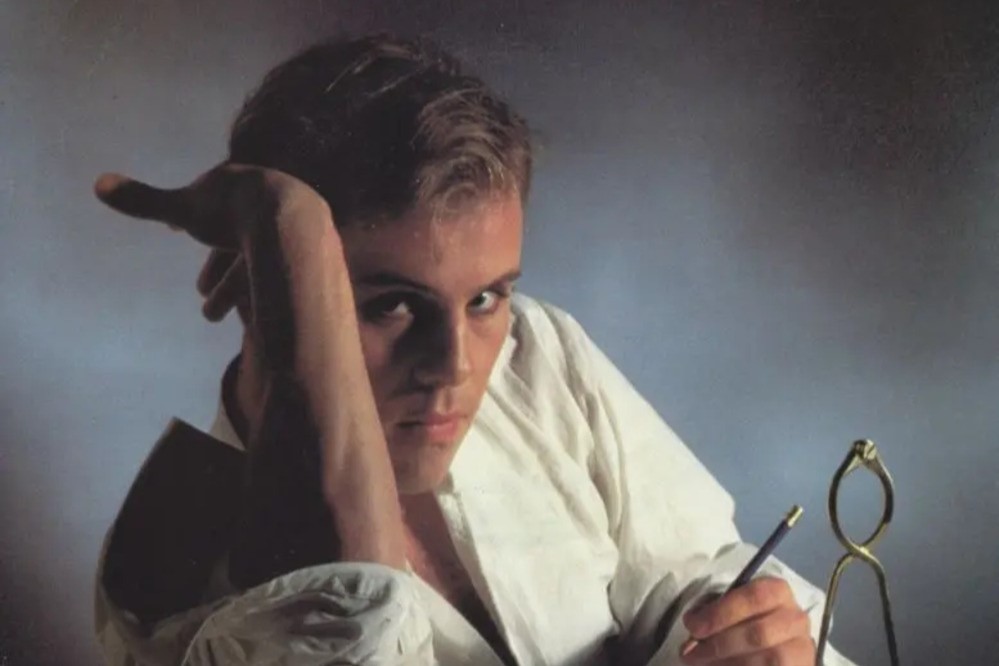

A superb, if not triumphant second album.

The mainstream can be a harrowing experience for artists on the rise. We’ve all seen the decline in quality of numerous acts when crunch time comes. But the scenario seems all too familiar to us now. An artist/group release their debut, which is met with acclaim, the pressure mounts to top the said album, confusion and desperation ensues, and a lackluster product of underwhelming potential is exposed. And this rule just doesn’t apply to debut albums, it’s a virus that can be contracted at any point in a musicians career.

Thomas Dolby, thankfully, is a rare exception to this rule. His previous album, which was also his debut: The Golden Age of Wireless, was a commercial success, pioneering a new genre of popular music called “synth-pop.” New wave had just took off in the charts, and Dolby took the sound a step further, crafting an unlikely hit in the process called “she blinded me with science.” His debut then went on to showcase the power of Dolby’s genius when it came to utilizing synth and electronics unfamiliar to pop music. It was safe to say he was on the rise.

So, Dolby’s follow up album: The Flat Earth, comes as a bit of a shock to critics and fans alike. Out of the 7 tracks present, only 2 (at a push) can be compared to the style of music on his debut. Furthermore, those 2 tracks are the only tracks on this album that are remotely similar.

When written down, this album should be a mess. It shouldn’t work as a whole. Instead of sticking to the trademark synth-pop sound which he helped develop, Dolby instead decides to take colossal new directions, flirting with funk, world, atmospheric ambience, flamenco and epic soundscape. At a glance, it looks like the man has lost all sense of direction, spiralling out of control in a desperate attempt to find a new sound.

Call it a divine blessing, but it works. It works better than it ever should. It seems that Dolby has a rare skill, to take a genre different to what he’s ever done before, spike it with his synth-drug, and make it flow so well on an album that is so sporadically different. The songwriting is top notch, and the session musicians all play a major part in bringing Dolby’s creations to life. Simply put, the man is a quality songwriter. “Dissidence” is an extremely strong opener with a funky flow, displaying some neat pop hooks but with spacious breakdowns. “Screen kiss” then expands on this spaciousness by ridding the drums and relying on a bed of synth and piano to create an atmosphere unlike anything he’s done before. By the time “I scare myself” comes in with its Latino feel, one might wonder if it’s the same album. Dolby somehow, makes this work.

That said, Dolby’s vocals take a different turn also. A much more mature impression and feel is created when compared to his debut. Gone are the random shrieks and Michael Jackson style hiccups found on his debut, and a more precise vocal flow is adopted. The backing singers also do a tremendous job, and take the spotlight very professionally when Dolby eases off.

Overall, it’s great to hear an artist making music for nobody but themselves, which ultimately, music should be about. As far as follow up albums go, this is absolutely solid, perhaps even better than his debut.

Bravo Thomas Dolby. 4.5/5