When Resident Evil 4 came out on Nintendo Gamecube in 2005, it was one of those watershed moments in video games. There had been third-person shooters before it and even the franchise experimented with it in 2003’s Resident Evil: Dead Aim, but nothing was ever as perfectly balanced as Resident Evil 4. After it came out, there was a tremendous paradigm shift in how third-person action games were designed.

There were a lot of elements at play that led to Resident Evil 4. Some parts of it were a result of the long development cycle that lead to the project getting restarted a few times. Early builds got scrapped and even led to Devil May Cry’s birth. Compounded on the remake of the first Resident Evil failing to turn a profit, the boys at Capcom decided to mix things up in a big way to save the series.

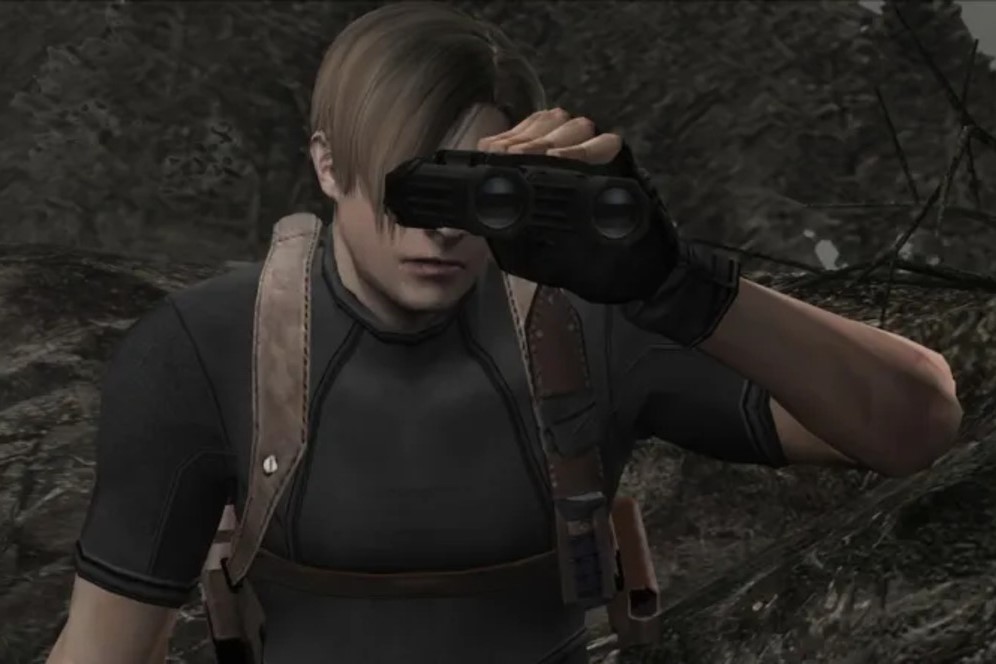

Resident Evil 4 is where the franchise abandons its “resilike“, cinematic camera perspective. The unique off-centered, over-the-shoulder POV would become the definitive camera system for almost every action game. After all these years and after getting its remake, how does the original game hold up? Which version should people play? Find out in this Resident Evil 4 (2005) review!

Resident Evil 4‘s story begins with Leon recounting the events from Resident Evil 2 and 3, which lead to the Umbrella Corporation going out of business. Shortly after, Leon becomes a secret agent and is sent on a rescue mission to save the U.S. President’s daughter from a Spanish cult.

When Leon arrives at the creepy village, it does not take long before things get out of hand and he finds himself wrapped up in something much bigger than a search and rescue mission. As it turns out, the Los Iluminados cult has been infected with a deadly virus that leads to nightmarish body-horror transformations. Not just the locals, but also some of the wildlife too and even the nearby aristocracy.

What makes Resident Evil 4‘s story so enjoyable is its perfect blend of humor, absurd action, and genuine horror. It flawlessly balances all of the elements to make a ride full of memorable moments, characters you care about, and even sequences that will make your blood run cold. It doesn’t take itself too seriously and is devoid of pretension.

The witty banter with Ashley is amusing due to Leon’s suave yet sarcastic tone. Leon and Salazar cracking jokes at each other and talking about movie scripts are hilarious. The Verdugo and Regenerators remain some of the most effectively scary and butt-clenching moments ever and it is thanks to genius creature design and execution.

There is a misconception about Resident Evil 4 being an action game. The reality is that it is still not too much of a departure from its roots than most gamers would think. Outside of the camera perspective change from the voyeuristic and picturesque fixed camera angles to the over-the-shoulder POV, Leon still controls with a tank-like configuration like all prior Resident Evil games.

There is no moving and shooting. There is no way to strafe and the camera controls only swivel 45 degrees left or right and can’t face behind Leon’s back. Aside from shooting or whipping out the knife, most actions are contextual with big arcadey button prompts on screen- something that would go on to be excessively copied by imitators.

The mechanics are the same as they were grounded in adventure game fundamentals. What changed is enemy behavior became much more complex, Leon (or Ada) has been given many contextual actions, and that gunplay full 360-degree aiming instead of three cardinal directions.

No matter which version of Resident Evil 4 you play, Leon must stop to aim and fire. This approach to combat has made the game a very distinct and tactical flavor. Every step becomes weighty with commitment and when you find yourself surrounded by raving creeping villagers with chainsaws, sickles, and pitchforks, choosing when to shoot becomes a risk because it leaves Leon vulnerable.

Aiming and shooting also feel weighty since it feels less like moving around a cursor on the screen and more like moving Leon’s arms and torso. Most guns have a laser and targeting enemy hit-boxes is very tight for a very accurate feel.

Resident Evil 4: Wii Edition allows players to aim and shoot at will with the IR-pointer. This circumvents a lot of Resident Evil 4‘s distinct feel when shooting, but it is hard to deny the sheer satisfaction of firing a single shot into the sky to perfectly hit a flying crow at 30 feet. The trade-off for the incredible accuracy is Wii Edition increased enemies in certain encounters, to balance the difficulty.

Shooting certain points of foes, like their knees or head, will put them in a state where Leon is given a contextual action promptly if he is close enough. This usually means a devastating melee attack that comes with plenty of I-frames. These attacks are extremely crucial in the harder modes for saving ammo and staying alive since exploiting these moments is seemingly the only way to survive.

Throughout its entire adventure, the way the mechanics are used never gets boring. Very late into the game, new enemy types are introduced, and Leon will be able to use a thermal vision scope to target invisible weak points. Other times, Resident Evil 4 seems like it relishes its video gamey-ness by throwing in the minecart sequence from Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom or a cheeky platform puzzle with a giant robot statue.

The first time you play Resident Evil 4, it will seem like the most hardcore game you ever experienced. It is full of details and consequences for actions that most games never consider. There are gimmicks used once and then never again- making the game always feel fresh and interesting at all times. It is no wonder why Resident Evil 4 has managed to be so replayable decades later.

Fun diversions like treasure hunting make you realize and appreciate the density of the level design. Details like the roaming chickens in the Pueblo that lay eggs (which are delicious), fire some rounds at the merchant’s gun range, or the fact that Leon can go spearfishing in the nearby lake add a lot of value to the experience. I didn’t even know that I could go fishing until my third or fourth playthrough, back in the mid-2000s.

Resident Evil 4 still feels like a modern game and a lot of that has to do with its forward-thinking game design. It did not pioneer quick-time-events, but when this game used them so effectively, you began to see many other action games similarly implement them. The only issue with the QTEs is that in the hardest mode, they can be brutal to complete. Wii Edition is especially hard because some waggle gestures don’t always register.

Resident Evil 4 is a linear game, but it does have some moments where the environment can open up in a big way. Salazar’s creepy castle is massive and most of it can be freely explored when it is opened up. You’ll want to because there are some areas where you can return to get some previously unobtainable supplies or weapons.

The level design is truly something to behold. The way areas connect and how some of the larger areas can be like mini-sandboxes or arenas makes Resident Evil 4‘s setting feel incredibly cohesive. Eagle-eyed gamers might even catch later locations in the distance, waiting to be explored.

The music also manages to be very memorable, despite being mostly ambient music with no melody. The save room and typewriter themes are especially beloved pieces that are soothing, yet ominous.

Before Resident Evil 4, the games in the franchise were known for being on the short side. Most of the time, players could beat these games in about six to seven hours on their first run. With replays, gamers could master the environment and item location; getting a run down to about two-three hours. Resident Evil 4 was the longest entry until Resident Evil 6; taking about twenty hours to beat.

Resident Evil 4 is a game that came out in 2005 on the Nintendo Gamecube, so it looks like a game from that era, on limited hardware. Despite that, Resident Evil 4‘s art direction is superb and manages to still look great despite its age. At worst, there are some obvious examples of repeating textures or mirrored textures, or flat trees.

Some textures and modeling are going to stand out as crude by today’s standards, but for the most part, everything reads as it is meant to. Details on characters’ faces and expressions hold up very well and everyone has a palpable weight to their animations.

The monsters are the real star of any Resident Evil game and this is no exception. Resident Evil 4 has a lot of imaginative and nightmarish, abominable creature designs. Impressively, there is some restraint with how some of the monsters are used and some end up only being used only a few times. In one instance, there is a powerful enemy that is only used in the unlockable side game, The Mercenaries, complete with a unique level too.

There are always going to be some smartasses that claim that “Resident Evil 4 is a good game, but a bad Resident Evil game”. The further along the franchise goes, the less sense this premise makes. Being inconsistent is the one thing that gamers can reliably expect from Resident Evil. This has become a large part of its charm because the franchise is always changing and reinventing itself.

One thing is for sure; Resident Evil 4 has no shortage of movie references, and this is the one aspect of the franchise that has managed to stay. Movie fans will have a lot of fun picking out the homages and you don’t even have to be a horror fan to notice some.

There are a ton of ways to play Resident Evil 4. It has been ported to most platforms and each one has something to offer. The Japanese versions offer an easy mode that radically changes enemy placement and cuts out some sequences. The PlayStation 4 and Xbox One versions have crispy image quality and 60 frames per second. If you have the money; Oculus Quest has the VR experience, but that comes with some censorship.

The preferred way to enjoy Resident Evil 4 is the Wii Edition for its novel control scheme. It is easily obtainable, and cheap and the hardware to run it is still accessible. Just be careful when playing in the hardest mode; you might give yourself whiplash.