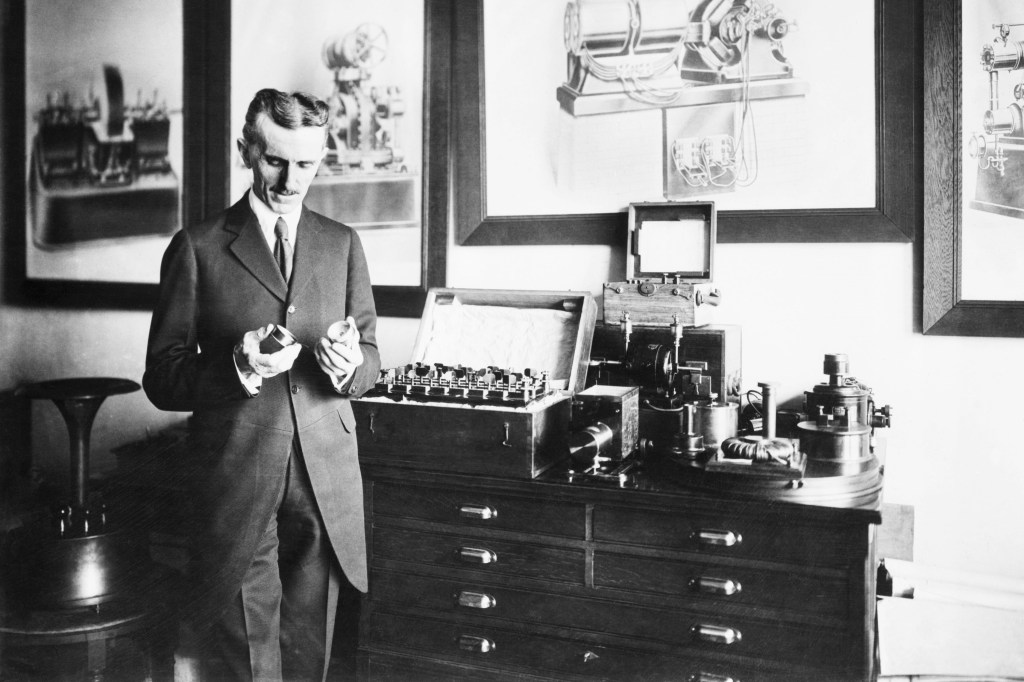

The physicist, electrical engineer, and inventor Nikola Tesla was born into a Serb family in Smiljan, Croatia, at midnight on July 9, 1856. The family moved to Gospi when he was 6 years old, and he went to school there and in Karlstadt (Karlovac). He then spent a year hiking in the mountains before attending the Austrian Polytechnic School in Graz. Financial difficulty forced him out during his second year, whereupon he went to Prague, where he seems to have taught himself in university libraries.

In 1881, Tesla got a job in the Central Telegraph Office in Budapest. While there he suffered a nervous breakdown and also conceived his revolutionary idea for an alternating-current motor. In 1882, he moved to Paris to work for Thomas Edison’s Continental Edison Company, and in 1884, he immigrated to the United States, again to work for Edison.

Later he worked independently as an inventor, originating many important electromagnetic devices, including a transformer known as the Tesla coil. The standard international unit of magnetic flux density is called the tesla, in his honor. He became a U.S. citizen in 1891.

Nikola Tesla died in New York on January 7, 1943, at the age of 86. Eight months after his death, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that he, and not the Italian physicist Guglielmo Marconi, was the inventor of the radio. His ashes were taken to Belgrade in 1957.

‘Tesla’s biographer, Margaret Cheney (1981), described him as a modern Prometheus, and many have noted his gigantic impact on science, and thereby on human life in general. For example, the engineer B. A. Behrend stated, “Were we to seize and eliminate from our industrial world the results of Mr. Tesla’s work, the wheels of industry would cease to turn, our electric cars and trains would stop, our towns would be dark, our mills would be dead and idle” (Cheney, 1981, p. 217). 1.C.M. Brentano noted in Tesla’s work “the importance of the achievements in themselves, as judged by their practical bearing; the logical clearness and purity of thought, with which the arguments are pursued and new results obtained; the vision and the inspiration, I should almost say the courage, of seeing remote things far ahead and so opening up new avenues to mankind” (Cheney, 1981, p. xvi).

While “people were to call him a wizard, a visionary, a prophet, a prodigal genius, and the greatest scientist of all time,” some also defamed him as “a faker and a charlatan” and “an intellectual boa constrictor” (Cheney, 1981, p. 81). Some fellow scientists resented what they saw as his bragging to the press over his inventions. As Cheney (1981) pointed out, Tesla, “spending more time in his ivory tower than on ground floors, was to be smiled on fitfully by fame and in the long run ignored by fortune” (p. 183).

Family and Childhood

Tesla’s parents were Milutin Tesla, a clergyman and spare-time poet, and Duka Mandic. He claimed that he inherited his photographic memory and his inventive genius from his mother, who could recite verbatim whole volumes of native and classic European poetry.

Tesla began, when only a few years of age, to make original inventions: “When he was five, he built a small waterwheel quite unlike those he had seen in the countryside. It was smooth, without paddles, and yet it spun evenly in the current. Years later he was to recall this feat when designing his unique bladeless turbine” (Cheney, 1981, p. 7). He attempted as a child to fly with the aid of an umbrella, jumping off the roof of a barn and knocking himself unconscious.

Tesla had an experience in his village much like one that Ludwig Wittgenstein had at a later date in the mountains. The village had purchased a fire engine, and an attempt was made to pump water, but no water came. He “flung himself into the river and found, as he had suspected, that the hose had collapsed. He corrected the problem.” Later he would recall, “Archimedes running naked through the streets of Syracuse did not make a greater impression than myself I was carried on the shoulders and was the hero of the day” (Cheney, 1981, p. 7).

Social Behavior

Cheney (1981) notes that Tesla was “a loner by preference when the time for lone operators was swiftly passing” (p. 77), and as “a perennial bachelor, working apart, not entering into corporate associations, and not mixing with friends — his personal life was obscure to outsiders. Such reclusiveness [marked] the career of one of the world’s leading figures in science and engineering” (p. xiii).

Although he was handsome and had a magnetic personality, Tesla was “quiet, almost shy” (Cheney, 1981, p. 79). Occultists and “odd men and women’ were attracted to him, believing him to be “a man of prophecy and great psychic power who ‘fell to Earth’ to uplift ordinary mortals through the development of automation” (Cheney, 1981, p. 82). As he seemed indifferent to women in a sexual sense, there were whispers of homosexuality, but there was no evidence, and he appears to have been celibate. For a period in New York, he lived almost a hermit’s existence. His friend Kenneth Swezey wrote, “Tesla’s only marriage has been to his work and to the world, as was Newton’s and Michelangelo’s … to a peculiar universality of thought. He believes, as Sir Francis Bacon did, that the most enduring works of achievement have come from childless men’ (Swezey, 1927, p. 60).

In New York he was friendly with a couple named Robert and Katherine Johnston, who cultivated an elegant social circle, and often visited them. Katherine’s letters to him suggest that she may have been in love with him. However, when Tesla “got around to responding,” in typical Asperger fashion, his tone was inappropriately chiding: He “only succeeded in being cruel, going on about how he had found her sister, whom he had recently met, much more pretty and charming than she” (Cheney, 1981, p. 109). This is much like Ludwig Wittgenstein’s reply to a woman who similarly had helped him (Fitzgerald, 2005).

Cheney (1981) described Tesla as a mutant or polymath: He was “part of no group or institution, he had no colleagues with whom to discuss work in progress, no formal, accessible repository for his research notes and papers. He worked not just in private but … in secret.” She pointed out that “the example set by Tesla has always been particularly inspiring to the lone runner” (p. 268).

The police regarded Tesla as a mad inventor. He showed sporadic anti-Semitism.

Narrow Interests/Obsessiveness

In his youth, Tesla’s favorite pastime was reading: He would read until dawn. He said that in his teenage years, his “compulsion to finish everything, once started, almost killed him when he began reading the works of Voltaire. To his dismay he learned that there were close to one hundred volumes in small print … But there could be no peace for Tesla till he had read them all” (Cheney, 1981, p. 18).

Regarding his method of invention, Tesla wrote, “I do not rush into actual work. When I get an idea I start at once building it up in my imagination. I change the construction, make improvements and operate the device in my mind. It is absolutely immaterial to me whether I run my turbine in my thought or test it in my shop. I even note if it is out of balance” (emphasis in original; 1919, p. 12).

Cheney (1981) noted that Tesla reported another curious phenomenon that is familiar to many creative people — that there always came a moment when he was not concentrating but when he knew he had the answer, even though it had not yet materialized. “And the wonderful thing is,” he said, “that if 1 do feel this way, then I know I have really solved the problem and shall get what I am after” (emphasis in original; p. 14).

At the Polytechnic School in Graz, Tesla brashly suggested to his physics professor that a particular direct-current apparatus would be improved by switching to alternating current. The professor responded that this was an impossible idea, but instinct told Tesla that the answer already lay somewhere in his mind. He knew he would be unable to rest until he had found the solution. (In fact, he wrote in his usual flamboyant way that it was a sacred vow, a question of life and death. He knew that he would perish if he failed (Cheney, 1981). Years later, as he was walking in a city park with a friend, the solution came like a flash of lightning. He had hit upon a new scientific principle of stunning simplicity and utility: the principle of the rotating magnetic field produced by two or more alternating currents out of step with each other (Cheney, 1981).

Tesla himself acknowledged, “I do not think there is any thrill that can go through the human heart like that felt by the inventor as he sees some creation of the brain unfolding to success … Such emotions make a man forget food, sleep, friends, love, everything” (Cheney, 1981, p. 107). In relation to marriage, he stated, “an inventor has so intense a nature with so much in it of wild, passionate quality, that in giving himself to a woman he might love, he would give everything, and so take everything from his chosen field. I do not think you can name many great inventions that have been made by married men” (Cheney, 1981, p. 107).

Like Edison, Tesla could work without sleep for two to three days. In the later part of his life, he took a great interest in pigeons. Indeed, an entire chapter of Cheney’s biography is entitled “Pigeons.” He regarded them as his sincere friends. According to Cheney (1981), “No one knew when the inventor began gathering up the sick and wounded pigeons and carrying them back to his hotel,” where he took care of them (p. 187).

Tesla told a strange story to John J. O’Neill (his first biographer) and another writer, as recounted by Cheney (1981). He said that he had fed thousands of pigeons over a period of years but that there was a special white pigeon — the joy of his life — that he loved as a man loves a woman, and that loved him and lent purpose to his life. When she was ill, he stayed beside her for days and nursed her back to health. Tesla said that finally, when the pigeon was dying, she came to see him and a blinding light came from her eyes. When she died, something went out of his life, and he knew that he would not complete his work.

Tesla wrote poetry but never published it, considering it too personal. He could recite poetry in English, French, German, and Italian.

Cheney (1981) noted that Tesla “threw out all accessories, including gloves, after a very few wearings. Jewelry he never wore and felt strongly about as a result of his phobias” (p. 79). He was afraid of germs and fastidious in the extreme.

Routines/Control

In his 30s, when he dined at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, Tesla followed a remarkable routine as illustrated in the following: “Eighteen clean linen napkins were stacked as usual at his place. Nikola Tesla could no more have said why he favored numbers divisible by three than why he had a morbid fear of germs or, for that matter, why he was beset by any of the multitude of other strange obsessions that plagued his life. Abstractedly he began to polish the already sparkling silver and crystal, taking up and discarding one square of linen after another until a small starched mountain had risen on the serving table. Then, as each dish arrived, he compulsively

calculated its cubic contents before lifting a bite to his lips. Otherwise there could be no joy in eating” (Cheney, 1981, p. 1).

Tesla feared being controlled by others but could be very controlling; for example, of his secretaries. Cheney (1981) noted that he subjected himself at a very early age to iron discipline in order to excel. He wrote that up to the age of 8, his character was weak and vacillating, but a book by a Hungarian novelist somehow awakened his dormant powers of will, and he began to practice self-control.

As a young man, he started to gamble on cards and games of billiards.

However, he was able to conquer this passion. Later in life he smoked heavily and drank coffee to excess but once again used his willpower to stop completely. It would be unusual for someone to do this as successfully as he did.

Language/Humor

Tesla spoke in a shrill, high-pitched, almost falsetto voice. Franklin Chester stated, “When he talks you listen. You do not know what he is saying, but it enthralls you … He speaks the perfect English of a highly educated foreigner, without accent and with precision … He speaks eight languages equally well” (Cheney, 1981, p. 78). He does not appear to have had a developed sense of humor.

Lack of Empathy

The young Tesla developed two concepts that would later be important to him: that human beings could be adequately understood as “meat machines,” and that machines could, for all practical purposes, be made human. Cheney notes, “The first idea may have done nothing to improve his sociability, but the second was to lead him deep into the strange world of what he called ‘teleautomatics’ or robotry” (p. 15). Thirty years later, he marveled at the unfathomable mystery of the mind.

Tesla displayed occasional streaks of cruelty: People with Asperger Syndrome often have aggression in them. In an interview that he gave to Collier’s magazine in 1926, Tesla described a future ideal society modeled on that of the beehive, with desexualized armies of workers whose sole aim and happiness in life would be hard work (Cheney, 1981).

Tesla was interested in eugenics. George Viereck (a German immigrant and friend of Tesla, who was later imprisoned for disseminating pro-Nazi propaganda) reported Tesla as saying that in a harsher time, survival of the fittest had weeded out less desirable strains, and proposing sterilization of the “unfit” in order to preserve civilization and the race. (Cheney, 1981, observed that one cannot say to what extent these sentiments originated with Tesla as opposed to Viereck.)

Naivety/Childishness

Tesla sometimes showed what might be interpreted as typical Asperger naivety in his business dealings. Soon after he started to work for Edison, he proposed a plan to make Edison’s dynamos work more efficiently — a major job. Edison responded, “There’s fifty thousand dollars in it for you — if you can do it.” Tesla’s salary was $18 per week at the time. Tesla worked flat out for months and succeeded in making the promised improvements, but when he asked for the fifty thousand dollars, Edison told him, “you don’t understand our American sense of humor.” When Tesla threatened to resign, Edison offered him a $10 per week raise (Cheney, 1981, p. 33).

When George Westinghouse said that his company could not continue to exist if it paid Tesla his full royalties, Tesla trusted him and tore up his contract. Thus, according to Cheney (1981), Tesla “not only relinquished his claim to millions of dollars in already earned royalties but to all that would have accrued in the future. In the industrial milieu of that or any other time it was an act of unprecedented generosity if not foolhardiness” (p. 49). He should have been a fabulously rich man based on his inventions, but in later life he had financial difficulties that even hindered his research.

In 1916, Tesla was summoned to Court to pay $935 to the city of New York in personal taxes. Cheney (1981) noted that the misfortune seemed unjustly cruel, coming at a time when Edison, Marconi, Westinghouse, General Electric, and thousands of lesser firms were thriving on the profits from Tesla’s patents. Tesla was penniless and swamped by debts and was even in danger of imprisonment.

The novelist Julian Hawthorne (only son of Nathaniel Hawthorne) described Tesla as having “the simplicity and integrity of a child” (Cheney, 1981, p. 78).

Nonverbal Communication

During his blockbuster lectures in the United States and Europe in 1891 and 1892, Tesla was “a weird, stork-like figure on the lecture platform” (Cheney, 1981, p. 51), yet he was handsome, and had a tremendously powerful personality. His hands were large and his thumbs abnormally long. “He was too tall and slender to pose as the physical Adonis, but his other qualifications more than compensated.” His eyes were “like balls of fire” (Cheney, 1981, p. 79).

Motor Skills

Tesla does not appear to have been clumsy or awkward, given his dexterity as an engineer and his almost professionally skillful billiard playing.

Comorbidity

Tesla appears to have manifested signs of mental and physical comorbidity in many phases of his life. For example, he experienced a “strange partial amnesia” at the start of the 1890s, and “was shocked to discover that he could visualize no scenes from his past except those of earliest infancy” (Cheney, 1981, p. 62).

In about 1881, he had a nervous breakdown during which he could hear the ticking of a watch from three rooms away. “A fly lighting on a table in his room caused a dull thud in his ear. A carriage passing a few miles away seemed to shake his whole body. A train whistle twenty miles distant made the chair on which he sat vibrate so strongly that the pain became unbearable. The ground under his feet was constantly trembling” (Cheney, 1981, p. 21). During this period his pulse fluctuated wildly, and his flesh twitched and trembled continuously. Yet his health returned, and soon after he solved the problem of the alternating-current motor that had been plaguing him for years.

As a child, Tesla contracted malaria and cholera; in his 60s, he was troubled by strange illnesses from time to time.

Conclusion

Like Charles Darwin, Stonewall Jackson, and John Broadus Watson, Nikola Tesla appears to have met the criteria for a diagnosis of Asperger’s disorder, which is defined more widely than Asperger Syndrome. Neither abnormalities of speech and language nor motor clumsiness are necessary for Asperger’s disorder under the American Psychiatric Association (1994) classification.

- Michael Fitzgerald, Former Professor of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry