Georgia Street is an east–west street in the cities of Vancouver and Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. Its section in Downtown Vancouver, designated West Georgia Street, serves as one of the primary streets for the financial and central business districts, and is the major transportation corridor connecting downtown Vancouver with the North Shore (and eventually Whistler) by way of the Lions Gate Bridge. The remainder of the street, known as East Georgia Street between Main Street and Boundary Road and simply Georgia Street within Burnaby, is more residential in character, and is discontinuous at several points.

West of Seymour Street, the thoroughfare is part of Highway 99. The entire section west of Main Street was previously designated part of Highway 1A, and markers for the ‘1A’ designation can still be seen at certain points.

Starting from its western terminus at Chilco Street by the edge of Stanley Park, Georgia Street runs southeast, separating the West End from the Coal Harbour neighbourhood. It then runs through the Financial District; landmarks and major skyscrapers along the way include Living Shangri-La (the city’s tallest building), Trump International Hotel and Tower, Royal Centre, 666 Burrard tower, Hotel Vancouver and upscale shops, the HSBC Canada Building, the Vancouver Art Gallery, Georgia Hotel, Four Seasons Hotel, Pacific Centre, the Granville Entertainment District, Scotia Tower, and the Canada Post headquarters. The eastern portion of West Georgia features the Theatre District (including Queen Elizabeth Theatre and the Centre in Vancouver for the Performing Arts), Library Square (the central branch of the Vancouver Public Library), Rogers Arena, and BC Place. West Georgia’s centre lane between Pender Street and Stanley Park is used as a counterflow lane.

East of Cambie Street, Georgia Street becomes a one-way street for eastbound traffic, and connects to the Georgia Viaduct for eastbound travellers only; westbound traffic is handled by Dunsmuir Street and the Dunsmuir Viaduct, located one block to the north.

East Georgia Street begins at the intersection with Main Street in Vancouver’s Chinatown, then runs eastwards through Strathcona, Grandview–Woodland and Hastings–Sunrise to Boundary Road. East of the municipal boundary, Georgia Street continues eastwards through Burnaby until its terminus at Grove Avenue in the Lochdale neighbourhood. This portion of Georgia Street is interrupted at several locations, such as Templeton Secondary School, Highway 1 and Kensington Park.

Georgia Street was named in 1886 after the Strait of Georgia, and ran between Chilco and Beatty Streets. After the first Georgia Viaduct opened in 1915, the street’s eastern end was connected to Harris Street, and Harris Street was subsequently renamed East Georgia Street.

The second Georgia Viaduct, opened in 1972, connects to Prior Street at its eastern end instead. As a result, East Georgia Street has been disconnected from West Georgia ever since.

On June 15, 2011 Georgia Street became the focal point of the 2011 Vancouver Stanley Cup riot.

The Lost Decade is commonly used to describe a period in Japan beginning in the 1990s, during which economic stagnation became one of the longest-running economic crises in recorded history. Later decades are also included in some definitions, with the period from 1991 through 2011 (or even through 2021) sometimes being referred to as Japan’s Lost Decades.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the Lost Decade

The Lost Decade is a term initially coined to refer to the decade-long economic crisis in Japan during the 1990s. Japan’s economy rose meteorically in the decades following World War II, peaking in the 1980s with the largest per capita gross national product (GNP) in the world. Japan’s export-led growth during this period attracted capital and helped drive a trade surplus with the U.S.

To help offset global trade imbalances, Japan joined other major world economies in the Plaza Agreement in 1985. In accord with this agreement, Japan embarked on a period of loose monetary policy in the late 1980s. This loose monetary policy led to increased speculation and a soaring stock market and real estate valuations.

In the early 1990s, as it became apparent that the bubble was about to burst, the Japanese Financial Ministry raised interest rates, and ultimately the stock market crashed and a debt crisis began, halting economic growth and leading to what is now known as the Lost Decade. During the 1990s, Japan’s gross domestic product (GDP) averaged 1.3%, significantly lower as compared to other G-7 countries. Household savings increased. But that increase did not translate into demand, resulting in deflation for the economy.

The Lost Decades

In the following decade, Japan’s GDP growth averaged only 0.5% per year as sustained slow growth carried over right up until the global financial crisis and Great Recession. As a result, many refer to the period between 1991 and 2010 as the Lost Score, or the Lost 20 Years.

From 2011 to 2019, Japan’s GDP grew an average of just under 1.0% per year, and 2020 marked the onset of a new global recession as governments locked down economic activity in reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic. Together the years from 1990 to the present are sometimes referred to as Japan’s Lost Decades.

The pain is expected to continue for Japan. According to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, recent growth rates imply that Japan’s GDP will double in 80 years when previously it doubled every 14 years.

What Caused The Lost Decade?

While there is some agreement on the events that led up to and precipitated the Lost Decade, the causes for Japan’s sustained economic woes are still being debated. Once the bubble burst and the recession took place, why did persist through successive years and decades? Demographic factors, such as Japan’s aging population, and the geopolitical rise of China and other East Asian competitors may be underlying, non-economic factors. Researchers have produced papers delineating possible reasons why the Japanese economy sank into prolonged stagnation.

Keynesian economists have offered several demand-side explanations. Paul Krugman opined that Japan was caught in a liquidity trap: Consumers were holding onto their savings because they feared that the economy was about to get worse. Other research on the subject analyzed the role played by decreasing household wealth in causing the economic crisis. “Japan’s Lost Decade,” a 2017 book, blames a “vertical investment-saving” curve for Japan’s problems.

Monetarist economists have instead pointed to Japan’s monetary policy before and during the Lost Decade as too restrictive and not accommodative enough to restart growth. Milton Friedman wrote, in reference to Japan, that “the surest road to a healthy economic recovery is to increase the rate of monetary growth to shift from tight money to easier money, to a rate of monetary growth closer to that which prevailed in the golden 1980s but without again overdoing it. That would make much-needed financial and economic reforms far easier to achieve.”

Despite these various attempts, Keynesian and Monetarist views on Japan’s extended economic malaise generally fall short. Japan’s government has engaged in repeated rounds of massive fiscal deficit spending (the Keynesian’s solution to economic depression) and expansionary monetary policy (the Monetarist prescription) without notable success. This suggests that either the Keynesian and Monetarist explanations or solutions (or both) are likely mistaken.

Austrian economists have, on the contrary, argued that a period of extended economic stagnation is not inconsistent with Japan’s economic policies that throughout the period acted to prop up existing firms and financial institutions rather than letting them fail and allowing entrepreneurs to reorganize them into new firms and industries. They point to the repeated economic and financial bailouts as a cause of—rather than a solution to—Japan’s Lost Decades.

What Is Japan’s GDP Growth Rate?

As of the first quarter of 2024, Japan’s annual GDP growth rate stood at a negative 0.2 percent compared to the same period one year prior. This indicates that the country’s GDP contracted slightly rather than growing.

How Big Is Japan’s Economy?

As of 2024, Japan boasts the world fourth-largest economy, behind the United States, China, and Germany.The country’s economy is characterized by a strong manufacturing sector and exports.

What Is Japan’s Lost Generation?

The “Lost Generation” is a concept closely related to Japan’s Lost Decades. The term refers to those Japanese university graduates who entered the economy during the employment freezes characteristic of the Lost Decades. This primarily includes people who graduated in the 1990s and 2000s. As a consequence of these circumstances, members of the Lost Generation may have had to take on low-wage temporary work over stable employment with robust retirement benefits—teeing up a potential pension crisis for the nation.

The Bottom Line

The Lost Decade, also known as the Lost Decades, refers to an extended stretch of economic stagnation in Japan beginning in the early 1990s. This era of poor economic performance has been characterized by low GDP growth, recessions, and deflation. Economists have posited multiple hypotheses to attempt to understand and explain the root causes and potential solutions of Japan’s economic downturn.

James Stavridis, the former NATO supreme allied commander for Europe, said Sunday that Russia has displayed “amazing incompetence” noting the several Russian generals that have died since the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine.

“In modern history, there is no situation comparable in terms of the deaths of generals,” Stavridis said during a radio interview on WABC 770 AM. “Just to make a point of comparison here, the United States in all of our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq…in all of those years and all of those battles, not a single general lost in actual combat.”

The former commander added that “on the Russian side, in a two-month period, we have seen at least a dozen, if not more Russian generals killed. So amazing incompetence.” He also criticized other aspects of the Russian military’s performance, by saying that they have an “inability to conduct logistics” and “bad battle plans.”

He also noted the loss of the Moskva, a Russian warship that the Pentagon said Ukrainians sunk with a missile last month. The loss of the ship was a $750 million hit to the Russian military, according to an analysis by Forbes Ukraine.

“It’s been a bad performance by the Russians thus far,” Stavridis said.

In late April, Newsweek compiled a list of several Russian generals who had been killed during the war. These include Major General Andrey Sukhovetsky, who served as the commanding general of Russia’s 7th Guards Airborne Division and deputy commander of the 41st Combined Arms Army, and was reportedly killed by sniper fire in February. Vladimir Frolov, deputy commander of Russia’s 8th Guards Combined Arms Army, was also reportedly killed last month.

A European diplomat, who spoke with Foreign Policy on the condition of anonymity about the deaths of Russian generals in March, said the failure of communications equipment has made them vulnerable.

“They’re struggling on the front line to get their orders through,” the diplomat said. “They’re having to go to the front line to make things happen, which is putting them at much greater risk than you would normally see.”

In an interview with ABC News last week, former U.S. ambassador to NATO Douglas Lute said he believes Russian forces can’t seize the Ukrainian capital city of Kyiv or replace Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s government.

“Putin is trying to assess what might be possible and looking for opportunities and he’ll grab the first good one available. Right now, there don’t seem to be many good opportunities for Vladimir Putin,” he said.

The Czech president has signed an amendment essentially equating communism with Nazism.

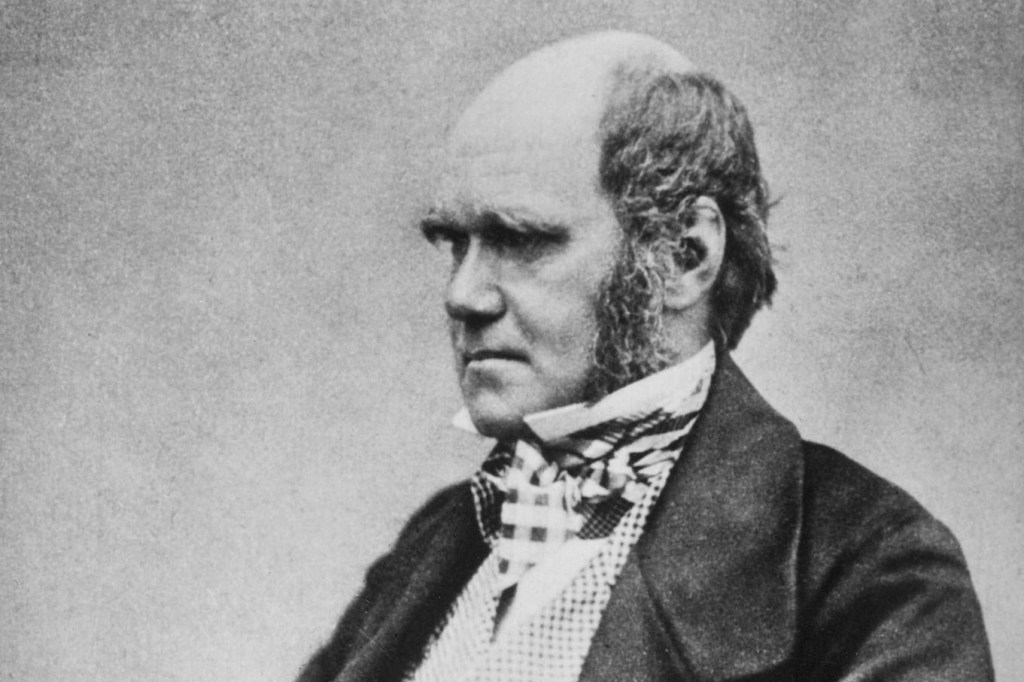

Charles Robert Darwin was born in Shrewsbury on February 12, 1809, the fifth chilod of a wealthy family. He studied at Edinburgh and Cambridge, and in 1831, was recommended as an unpaid naturalist on the HMS Beagle, which was about to embark on a surveying expedition to South America. His studies on this voyage formed the basis for much of his later work on evolution and natural selection.

Darwin married his cousin Emma Wedgwood in 1839. They had 10 children, 3 of whom died in infancy. He lived in Kent, studying flora and fauna, and in 1859 published his magnum opus, The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. He continued his studies despite ill health, and published many other works. He died on April 19, 1882, and was buried in Westminster Abbey.

This chapter explores the question: Did Darwin meet the criteria for Asperger Syndrome (Gillberg, 1991) or schizoid personality, or, indeed, was he simply a loner? (Wolff, 1995).

Family and Childhood

Darwin’s paternal grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, was a well-known intellectual who was “as gifted in the field of literature as he was in science … the archetypal gentleman polymath of his era.” Darwin’s maternal grandfather was the pottery magnate Josiah Wedgwood; both grandfathers were members of the Lunar Society, “a collection of wealthy men interested in machines and mechanical devices who met monthly at the time of the full moon’ (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 4).

Charles’ father, Robert, was born in 1766. A “larger-than-life character,” he had a large medical practice in Shrewsbury, and was “in turns kindly and severe” (White & Gribbin, 1995, pp. 5, 6). He married Susannah Wedgwood in 1796.

As a young boy Charles became a “great hoarder, collecting anything that captured his interest, from shells to rocks, insects to birds’ eggs” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 6) and liked to go on long solitary walks (on one of which he was so deep in thought that he fell into a ditch) (Desmond & Moore, 1992).

His early childhood was a lonely time. On one occasion he beat a puppy because of the “sense of power it gave him” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 7). The death of his mother in 1817, when he was 8 years old, disturbed him greatly. His father became depressed and decreed that Susannah’s death not be mentioned, so Charles had no opportunity to express his emotions on the matter.

One of Darwin’s daughters, Elizabeth, may have shown signs of Asperger Syndrome. According to White and Gribbin (1995), “She never married and was content to live at home and to do odd jobs around the house and garden. A quiet and retiring child, she grew into a taciturn and reserved adult” (p. 237).

Social Behavior

As a child, Charles played solitary games in the vast family home. He was always something of a loner, and was noted to have an isolated, introspective nature. Young Charles detested the regimented learning of school; he would dash off afterwards and spend the evening at home, in his own room, although this was not allowed and he would have to run the mile back to school before locking-up time. His classmates regarded him as “old before his time and a very serious fellow” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 9).

Around his 30th birthday he considered marriage. “In his usual analytical fashion he drew up a list of pros and cons to assess the situation.” He was concerned that “marriage would stifle him, prevent him from travelling if he decided he wanted to, that it would hinder his work by occupying too much of his time and that children might disturb his peace. It was an entirely selfish list of good and bad points, with scant concern for love or emotion; a purely scientific, pre-experimental treatment” (White & Gribbin, 1995, pp. 112-113). Despite his shyness and gentlemanly demeanor, he began to form a relationship with his cousin Emma Wedgwood, whom he had known since childhood.

Darwin was a great thinker, but had very little self-confidence. He was “a very humble man, totally dedicated to his studies, a scientist who worked meticulously and in solitude” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 2).

Narrow Interests/Obsessiveness

Throughout his life, Darwin was prone to obsession with particular living creatures. These included, at various times, orchids, beetles, barnacles, and earthworms. Science fascinated him from the age of 10. On holiday in 1819, he “spent most of each morning wandering off on his own to watch birds or to hunt for insects. Hours later he would return with specimens and spend the rest of the afternoon and early evening bent over his finds, devising methods of cataloguing them and trying to ascertain the species to which the various creatures belonged” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 10). He also spent hours poring over books about natural history in his father’s library. After he and his brother Erasmus set up a science laboratory at their home, Charles was given the nickname “Gas” at school. He spent most of his allowance on buying the latest gadgetry and chemicals for his hobby, and continued with his experiments alone after Erasmus left for Cambridge. The brothers kept up a correspondence that was “full of chemical chat … leaving little room for comment on family matters” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 11).

In his teenage years, Charles “displayed an insatiable desire to kill birds of any variety … It was a peculiar obsession,” according to White and Gribbin (1995, p. 12). He also liked to slaughter small animals, even though he was squeamish as a medical student and hated dissection. His father commented that he “cared for nothing but shooting, dogs, and rat-catching” and that he would “be a disgrace to himself and all his family” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 13). At Edinburgh University, he spent an inordinate amount of time reading the latest scientific, medical, and political literature. He frequently went off into the country from Edinburgh to collect specimens, neglecting his medical studies to follow his obsession. When he found a genuine interest, he would pursue it with an unmatched intensity.

At Edinburgh, Darwin began his life-long fascination with geology; while studying at Cambridge, he developed a “new obsessive fascination with entomology, and in particular, beetles” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 21). He then became very interested in botany. On the Beagle expedition, he studied the wildlife of the Brazilian jungle and was particularly fascinated with the beetles and other insects living on the jungle floor. He began collecting fossil remains, made “detailed observations of flora and fauna and when he was not collecting wildlife, he doggedly hammered away at rock faces” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 62). The voyage lasted more than four years.

In 1846, Darwin started to study the barnacle, “a task which occupied almost all of his time for the next eight years” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 144). Although his health was bad, he had deliberately chosen to cut himself off from the world to concentrate on this arduous, tedious work, which involved using a microscope for hours at a time — each of his “beloved barnacles” was the size of a pinhead. He published four volumes on them, two describing living species and two describing fossil species. In the 1870s, he turned his attention to earthworms and the way they affect the environment, keeping thousands of them in jars in his study and greenhouse, and conducting experiment after experiment on them. He published a book and 15 scientific papers on earthworms.

In his autobiography, Darwin stated, “I think that I am superior to the common run of men in noticing things which easily escape attention, and in observing them carefully”; he also stated, “My habits are methodical” and referred to his “unbounded patience in long reflecting over any subject — industry in observing and collecting facts” (White & Gribbin, 1995, pp. 300-301).

Routines/Control

Darwin led his life in a highly organized fashion, rarely altering his routine. As the children began to leave home and Charles and Emma grew older, the pattern of their lives became even more mechanical and regulated.

During middle and old age, Darwin walked the same path almost every day on a strip of land near his house, surrounded by a gravel path. When he first formed the habit, he used to count the number of times he completed the circuit, kicking a flint onto the path at the end of each lap. It was on these walks that Darwin did most of his thinking: “Counting the laps and kicking the markers was all part of the mantra guiding the pattern of his thoughts” (White & Gribbin, 1995, pp. 259-260). Every night after dinner, Darwin played two games of backgammon with Emma. They kept a running score: At one point he was able to report that he had won 2,795 games while she had won only 2,490.

Darwin’s extremely thorough and methodical cataloguing of his specimens might suggest an urge to establish control over the chaotic diversity of nature.

Language/Humor

There is no evidence that Darwin had problems in these areas. His writings are of a very high standard.

Lack of Empathy

Darwin’s clinical views on the meaning of human existence and the primacy of “truth,” as he saw it, made it difficult for him to be flexible or to compromise, even where the feelings of others were concerned. For example, he took a casual attitude to his own wedding. He appears to have regarded the ceremony as rather silly, showing little regard for the feelings of Emma or the two families. There was no proper reception; instead, he “whisked Emma off to the railway station with almost indecent haste and in so doing antagonized a number of relatives” (White & Gribbin, 1995, pp. 115-116).

Darwin “always had the habit of reducing everything to its fundamentals, of parrying all arguments with cold scientific logic” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 114). This made it difficult for Emma to explain her views on religion to him: She had to resort to writing him letters, in which she could pour her heart out and describe her feelings without clashing over meaning. In 1873, his method of writing to Huxley over some money that Huxley needed was more than a little clumsy, in Emma’s opinion — further evidence of a lack of empathy.

Naivety/Childishness

Darwin was extremely slow to publish his theory of evolution and was unnecessarily cautious. While he delayed, the Welsh naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace came up with a similar theory. Darwin had been warned repeatedly that this could happen if he did not publish but apparently failed to perceive the danger.

Motor Skills

There is no evidence that Darwin had any difficulty in this area.

General Health

Darwin suffered from depression, especially after the death of his daughter Annie in 1851; he wrote to his colleague Joseph Hooker in 1875 expressing a “semi-serious desire to commit suicide” (White & Gribbin, 1995, p. 270). He was plagued by a succession of illnesses throughout the second half of his life: It was suggested that he suffered from multiple allergies and was hypersensitive to heat.

Conclusion

As far as Gillberg’s (1996) criteria for Asperger Syndrome are concerned, Darwin does not meet the speech and language or the motor clumsiness criteria. However, according to Gillberg, motor clumsinessmay may be less a feature of high-IQ persons with Asperger Syndrome.

Neither abnormalities of speech and language nor motor clumsiness are necessary for a diagnosis of Asperger disorder under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) classification; therefore, Darwin meets the criteria for Asperger disorder, which is broader in its definition than Gillberg’s criteria.

Did Darwin have schizoid personality disorder? Though he had a detachment from social relationships, it was not pervasive, and he was a family man. Certainly, he chose solitary activities and took pleasure in these activities. He was not indifferent to criticism and did not show emotional coldness. Therefore, he did not meet the criteria for schizoid personality disorder, as defined by DSM-IV.

Did he meet the criteria for “loner” (schizoid personality) as defined by Wolff (1995, 1998)? He did demonstrate the following relevant features: social isolation and idiosyncratic behavior, high IQ, empathy problems, increased sensitivity, and single-minded pursuit of special interest. Ssucharewa (1926) noted that such persons tend to come from gifted families; Darwin’s family was certainly gifted.

Regarding schizoid personality in childhood, Wolff (1998) noted that such children’s special patterns were often sophisticated, quite unlike the simple, repetitive, stereotyped behaviors and utterances of autistic children. This applies to Darwin. Indeed, when Wolff followed up her loners, she found that two exceptionally gifted children — a musician and an astrophysicist — were able to transform their special interests into useful contributions to society, like Charles Darwin.

Family history studies are necessary to elucidate the link between Asperger disorder and schizoid personality. It is possible that great creative achievement, such as that of Darwin, is a much more difficult task without a capacity for solitariness and extraordinary focus on a specialized topic.

This trend of publishers “remaking” their legacy IPs of the past is not going to stop or even slow down. It’ll probably accelerate until they are literally out of source material. And the reason why is that we, as gamers, are in depression both creatively and economically. We have long past the point of running out of new ideas. We are now actively avoiding new and original design concepts because the risk involved is simply too high. Even if a developer, like Konami, wanted to make original Silent Hill games, they no longer have the staff nor the ability to justify any untested ideas to their shareholders. Capcom are the same way, just in a less desperate situation overall. This is a reality that everyone involved in gaming seems to recognize deep down, whether consciously or unconsciously.

So the new meta has become to take established games of the past and to leverage their reputation to market a new fleet of safe, accessible, commercially viable “remakes.” Capcom have been extremely successful in doing this with Resident Evil, so it makes complete sense that Konami would follow the formula for their own Silent Hill series.

What seems to be lost in the conversation around these remakes, or maybe purposely ignored, is the artistic legacy of the original games is not being respected and is often actively belittled in the marketing of the new game. Gaming has never been too bothered about artistic integrity, but when it comes to critical analysis of games like Silent Hill 2 Remake, I think there needs to be a more holistic discussion of the debt these remakes owe their source material it terms of their overall design, rather than just treating the original game like a costume that the latest Last-Of-Us-Like can slip on and then pass itself off as somehow representative of the original game.

Ironically, the only backlash Remakes ever seem to face is when they change the story and aesthetic elements of the original game, rather than the core gameplay systems and level design. In fact, the more the new remake eliminates the unique aspects of the original (like fixed camera angles and tighter pacing, in OG Hill 2’s case) the better. And if the new elements of the remake are under-developed or fairly basic, like this remake’s are, then that’s fine too because it’s all a net improvement anyway, right?

The challenge I’ve come up against, that I think a lot of other reviewers more critical of these remakes face, is that just talking about the topic generally is cute and everything, but what really matters is taking these concepts and actually applying them in real game reviews. Some sort of method of analysis needs to be developed, which I demonstrate the best I can in this review, because otherwise every other gaming outlet (most of them literally owned by IGN now) will just treat the remake as a product and declare it a masterpiece for following the remake formula so well.

The most coherent standard I can think of when it comes to my Remake reviews is to hold them up to what they should faithfully represent and build upon from the original game (including its unique mechanics) and also how well the “modernized” elements of the game hold up on their own terms, without the excuse of “being faithful” to the original game. None of this is faithful, let’s be honest. So if it’s not faithful, at least make it good.