https://moviemusicuk.us/2017/11/30/the-last-emperor-ryuichi-sakamoto-david-byrne-and-cong-su/

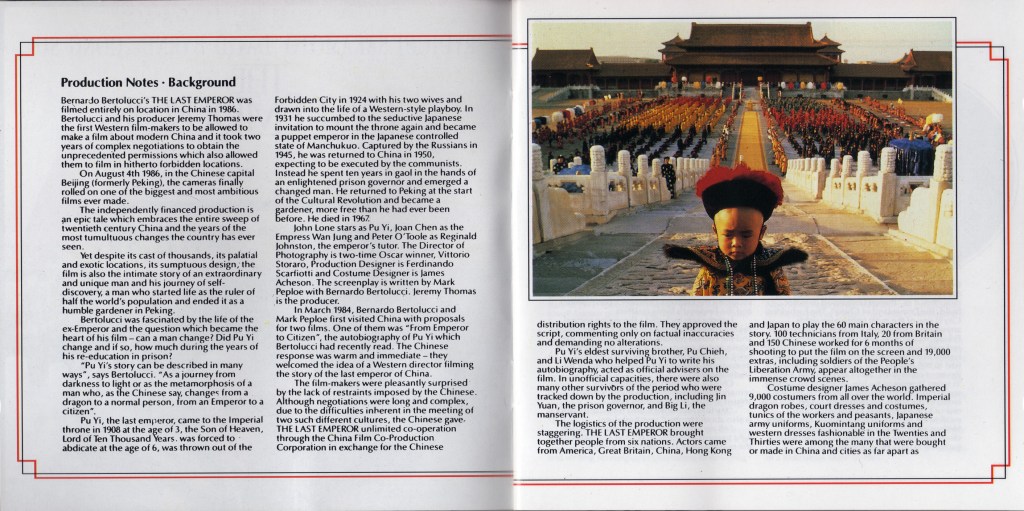

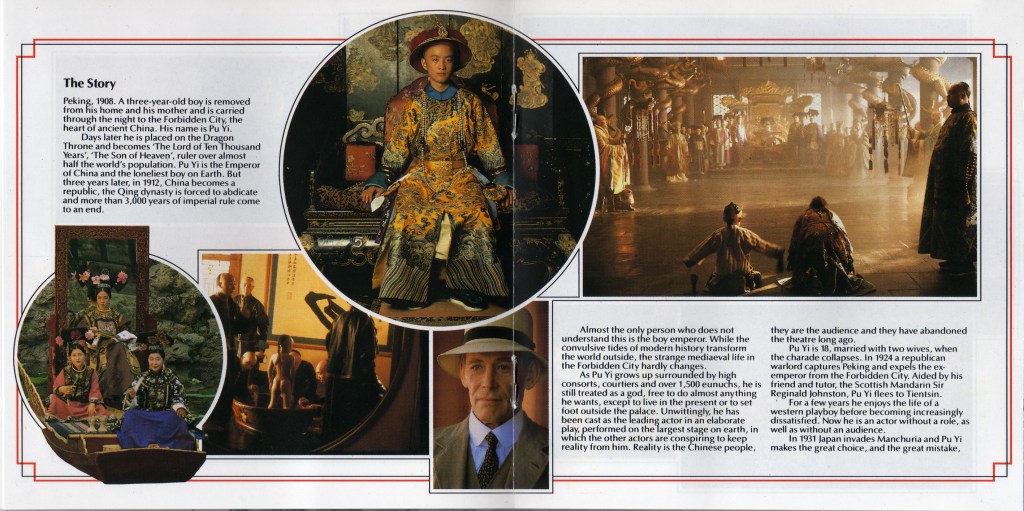

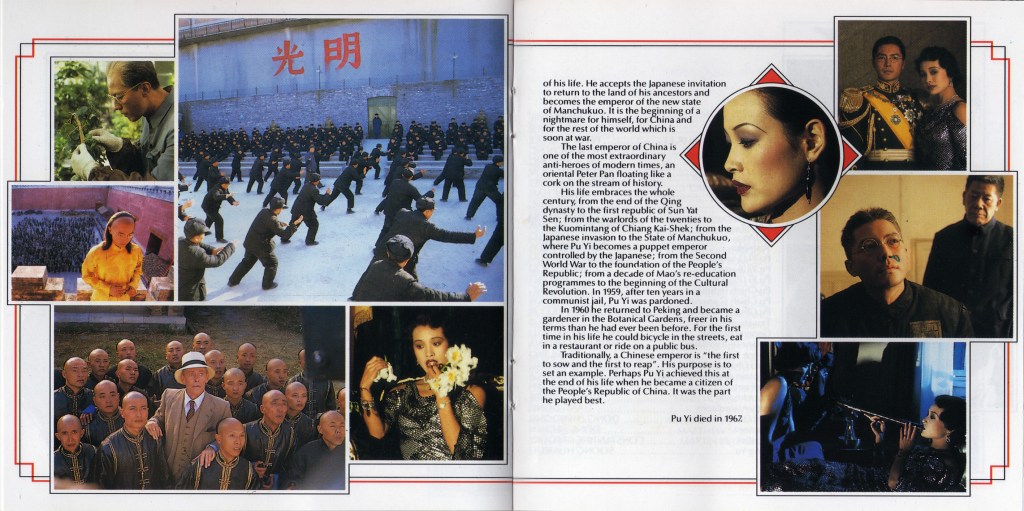

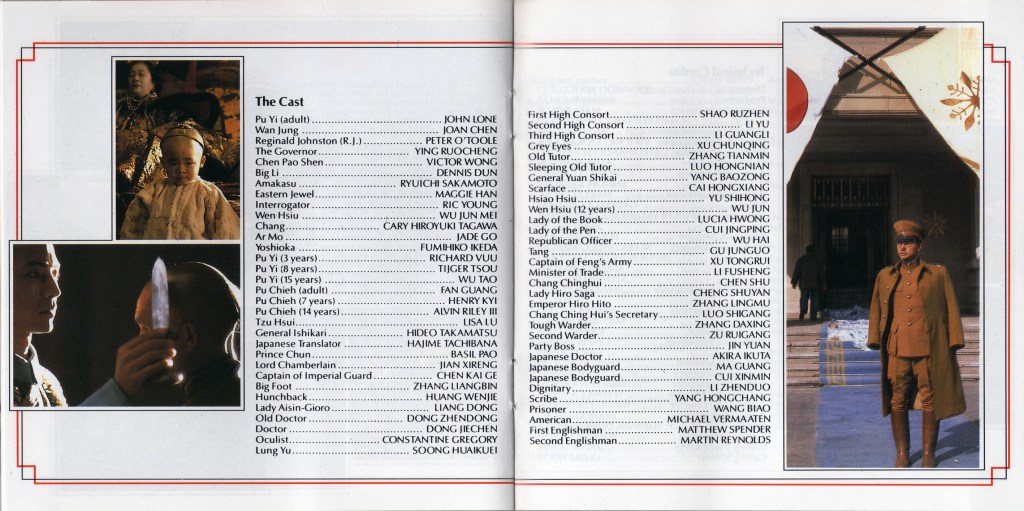

They don’t make movies like The Last Emperor anymore. A lavish historical epic directed by the great Italian filmmaker Bernardo Bertolucci and starring John Lone, Joan Chen, and Peter O’Toole, the film tells the life story of Pu Yi, the last monarch of the Chinese Qing dynasty prior to the republican revolution in 1911. It is set within a framing story wherein the adult Pu Yi – a political prisoner of communist leader Mao Zedong – looks back on his life, beginning with his ascent to the throne aged just three in 1908, and continuing through his early life growing up in the Forbidden City in Beijing, and the subsequent political upheaval that led to his overthrow, exile, and eventual imprisonment. It’s an enormous, visually spectacular masterpiece that balances great pageantry and opulence with the very personal story of a man trying to navigate his life as a figurehead and monarch, and how he balances that with his private life and his political and social importance. It was the overwhelming critical success of 1987, and went on to win nine Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay, as well as a slew of technical awards for Art Direction, Cinematography, Editing, Costume Design, and Score.

The score for The Last Emperor was by as unlikely a trio of composers as you could possibly imagine: Ryuichi Sakamoto, David Byrne, and Cong Su. Sakamoto was an acclaimed pop musician in his native Japan, and had scored his first films three or four years previously, but was most known internationally as a result of his 1983 score for the film Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence, in which he also appeared in the main supporting role opposite David Bowie. Byrne was the unconventional and eccentric front man of the post-punk rock band Talking Heads, who had enjoyed a fair amount of chart success with songs such as “Once in a Lifetime” in 1981, “Burning Down the House” in 1983, and “Road to Nowhere” in 1985, but had shown no indication that he was capable of writing a serious orchestral score for a prestigious drama film. Cong Su, meanwhile, was a complete unknown, an expert on Chinese classical music who split his time as a composer and musicology teacher between Beijing and Germany, but had never written for film prior to this. Quite how Bertolucci brought these three diverse individuals together to work on The Last Emperor is a mystery, but through some strange alchemy it all works; the soundtrack is a theme-filled exploration of the sounds and musical traditions of Imperial China, filtered through some very contemporary sensibilities.

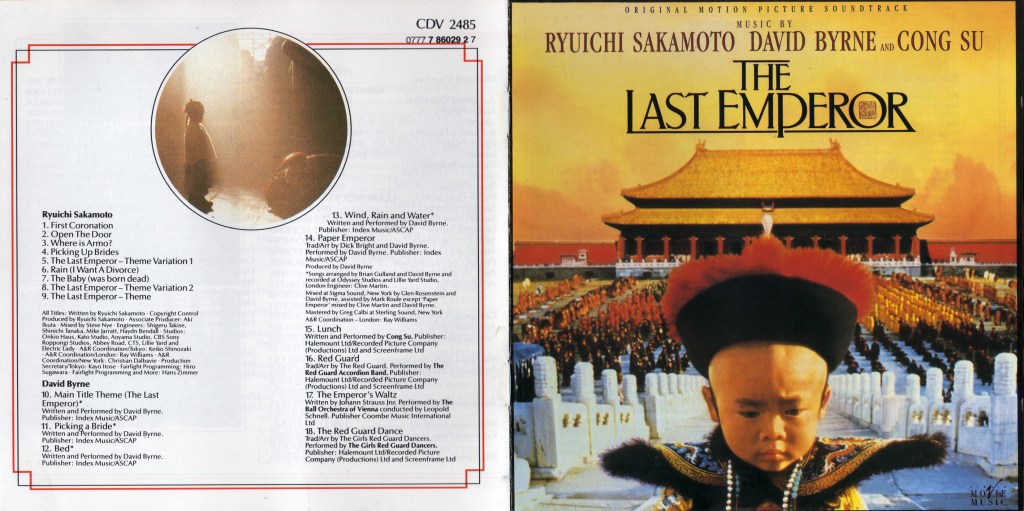

Sakamoto’s contribution to the score comprises nine cues and is focused around his main theme, a beautiful, lyrical melody for the full orchestra, with the main recurring idea often conveyed by an erhu or a guzhengzither. It’s a soft theme, slightly wistful, slightly introspective, but which often rises to swelling brass crescendos during its more dramatic second half. The two specific variations of the theme offer slightly different takes on the melody; “Variation 1” has an ecclesiastical tone, featuring a duet for guzheng and choir, while “Variation 2” is more abstract, with a much more prominent Fairlight synthesized element which stands out like a sore thumb, but is nevertheless typical of Sakamoto’s experimental nature. It’s interesting to note that one of the credited synth arrangers and producers on Sakamoto’s part of the score was none other than Hans Zimmer, the then-29-year-old assistant to composer Stanley Myers, who was still a year away from writing Rain Man. I wonder how much he contributed to this cue’s sound specifically?

The other cues in Sakamoto’s segment tend to offer little vignettes of Pu Yi’s life as a toddler in the Imperial Palace, and help to convey the romance and majesty of his environment, as well as the inquisitiveness the little boy shows at his wondrous surroundings. “First Coronation” is a thrilling fully-orchestral enhancement of the main theme with a great deal of scope and melodrama, and an especially notable performance for a konghou harp. “Open the Door” is more stark and tragic sounding, with a bank of searing strings allowing little Pu Yu’s shock and horror at the death of his father to hit home, while the more strident and rhythmic second half is the closest the score comes to having an action cue. “Where is Armo?” is warmer, with rich classical strings and a welcoming sound, but which still works in some playful traditional Chinese instrumental ideas that continue on into the evocative and ancient-sounding “Picking Up Brides.” “Rain (I Want a Divorce)” continues the synths that Variation 2 added into the mix, before presenting a lush and fulsome scherzo for the string section that has a lyrical sense of joie de vivre. “The Baby (Was Born Dead)” is more downbeat, with harp and solo piano dominating and creating a somber mood.

Byrne’s contribution to the score comprises five cues, but the first one – “Main Title Theme (The Last Emperor)” – is actually the score’s most recognizable element, as it plays over the film’s stylish opening credits sequence, and accompanied the three composers as they made their way to the stage to accept their Oscars from Patrick Swayze and Jennifer Grey at the 1987 Academy Awards. The main theme emerges from a set of evocative Chinese percussion items, with the melody being carried by a gorgeous, lilting erhu. It’s traditional and wholly steeped in Chinese classical music, but it has a real emotional weight that will connect with westerners; it’s repetitive and almost hypnotic in nature, picking up layers of instruments as it develops, and is quite magnificent.

Byrne’s other cues are, inevitably, less powerful than his main theme, but are no less effective. It’s interesting to note just how much Byrne relied on classic Chinese music in his cues – much more so than Sakamoto did – which is unexpected considering that Sakamoto comes from a complementary musical culture, whereas Byrne was born in Scotland and grew up in Maryland. “Picking a Bride” is a playful, rhythmic piece for a variety of traditional instruments, most notably a small section of ethnic woodwinds, and what sounds like a Chinese version of an accordion. “Bed” is more abstract, featuring a number of scratched and scraped metallic percussion ideas over a bed of tremolo strings and, latterly, elegant flutes, amid the vaguest hints of his main theme. “Wind, Rain, and Water” revisits the accordion sound, and is quite jaunty with a sort of sea shanty-esque vibe, while “Paper Emperor” uses the much more western combination of brass and slightly jazzy oboes to convey a sense of bitterness and despondency.

Cong Su’s contribution to the soundtrack album comprises just one cue – “Lunch” – but there is much more of his music in the film; Su was basically responsible for writing all the period-specific Chinese source music one hears in and around the imperial palace during Pu Yi’s childhood. Most of it sounds much like “Lunch,” which is a soft, quiet, intimate piece for a number of Chinese folk instruments, including a dizi flute, a pipa lute, a guzheng, various metallic percussion items, and the ubiquitous erhu. It’s very authentic sounding, and has a calming, peaceful tone. The other cues are two traditional pieces, “Red Guard” and “The Red Guard Dance,” both of which are performed diegetically on-screen by The Red Guard Accordion Band and The Girls Red Guard Dancers respectively, and a lovely orchestral rendition of Strauss’s popular “Emperor Waltz.”

It’s interesting how the careers of these three composers have diverged since The Last Emperor. Sakamoto, of course, has gone on to enjoy an outstanding career as one of Japan’s pre-eminent film composers, with titles such as High Heels, Little Buddha, Snake Eyes, Femme Fatale, Appleseed, and The Revenant among his more popular works. Byrne diversified greatly, releasing more albums with Talking Heads, several others as a solo artist, and contributing to art projects including ballets, operas, theatre works, and a handful of other films including 1988’s Married to the Mob and 2003’s Young Adam. Meanwhile, Cong Su only scored two more films, both of them in China, before settling down to a quiet life in musical academia in Italy.

Think about all the great scores released in the past twenty years or so which have blended western orchestras with Chinese solo instrumental textures: Rachel Portman’s The Joy Luck Club, Conrad Pope’s Pavilion of Women, Klaus Badelt’s The Promise; scores by Tan Dun and Shigeru Umebayashi and Zhao Jiping; heck, even the Kung Fu Panda movies. Now try to think of one from a film that was released prior to 1987 – there aren’t many, right? In many ways, The Last Emperor was the pioneer which paved the way for many of these great scores, which makes it all the more curious why people so rarely talk about The Last Emperor today, thirty years after it’s release. Many scores from 1987 are beloved – The Untouchables, The Witches of Eastwick, Predator, Robocop, Masters of the Universe, Hellraiser, and Empire of the Sun among them – and The Last Emperor absolutely deserves to be on that list. It would not have been my choice to win the Oscar, but it remains a genuinely excellent score, full of richness, melody, emotion, and which allowed the traditional music of Imperial China to enter the film music mainstream.