Enjoying these old commercials and content? The best way to support the channel is to go to my eBay store, Obsolete Treasures, which features lots of vintage items. You’ll find all sorts of cool things there, including trucker hats/baseball caps, old electronics/stereos/computers/video games, unique jackets, ephemera, and other weird/interesting items from the past (and some newer items that might even be useful). In addition to the sale price, I will receive a commission if you purchase from my store using this link: https://ebay.us/kMTuOX

Author: ulaghchi

Understanding AuDHD: When Autism And ADHD Overlap

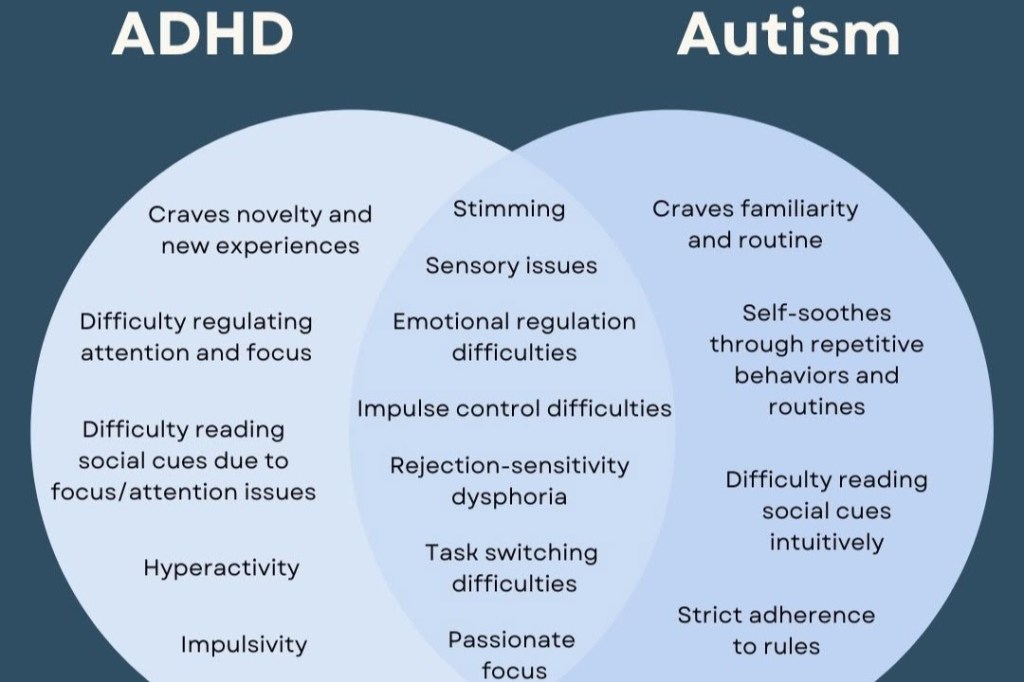

Autism and ADHD have long been seen as two distinct forms of neurodivergence. But what if they overlap? The term AuDHD has emerged to name this experience, offering validation and bringing clarity to patterns of thought and behaviour that might once have felt confusing or contradictory.

At Leone Centre, we often meet people who have spent much of their lives trying to “make sense” of themselves. They may have been told they are too much, not enough, too sensitive, too intense or too distracted.

Yet what if those very traits are not deficits, but expressions of a different kind of perception, one that deserves listening, not managing?

What happens if we look past those labels? What if, instead of fitting ourselves into categories, we approach these experiences with compassion and curiosity? Often, what emerges is a richer story: the layered, nuanced reality of minds that hold both ADHD and autism, and the humanity that lives beyond any one diagnosis.

AuDHD is not an official term. It’s a word that has emerged from lived experience, from people searching for a language that feels closer to the truth of who they are. It points to the meeting place of autism and ADHD, describing two ways of being once thought to be distinctly separate.

Until 2013, it was not possible to be diagnosed with both ADHD and autism. Systems demanded a choice and one explanation over another. Imagine what that meant for the many who lived with both? Their stories trimmed to fit whichever description seemed most pressing at the time.

Clinically, autism and ADHD are diagnosed separately using DSM-5-TR or ICD-11 criteria, and co-diagnosis is now permitted.

Today, AuDHD offers a bridge that emerges from lived experience, not from textbooks, but from people searching for words that feel closer to the truth. It acknowledges that some people don’t fit neatly into one box or another, that their reality is woven from both to varying degrees. With growing awareness, space is opening for a more balanced approach to research and support that hadn’t been pursued before.

Understanding this overlap is not about collecting labels, but about giving a voice to the challenges and triumphs of a different way of perceiving the world. What possibilities open up when we stop reducing people to categories and begin to notice the richness of their lived experience?

With the ambiguity surrounding AuDHD, many may lean towards doubting their experience as an isolated one. But the statistics tell a different story.

You may be surprised to find that:

- Recent research shows that around four in ten autistic individuals also meet criteria for ADHD, while between one and three in ten people with ADHD show significant autistic traits, depending on age and method of assessment.

- A large 2024 school-population study found a 1% co-diagnosis rate, highlighting that overlap is not rare but often under-identified in community samples.

- Prevalence also varies across development: symptoms may appear more differentiated in early childhood and blend in adulthood, which can delay recognition.

Awareness shifts the story. Instead of self-doubt, it can bring a sense of recognition: you are not alone, and you are not an outlier. It also reminds us that no two experiences are identical.

One of the reasons many neurodivergent individuals might question whether they have both autistic and ADHD traits is how we associate attention with either.

In ADHD, the “AD” stands for “attentional deficit”. This can often lead to the assumption that having ADHD translates as an inability to pay attention. In reality, many ADHDers don’t lack attention but experience it differently. They often show interest-driven attention, experiencing periods of hyperfocus, intense and sustained concentration on highly stimulating or rewarding tasks. For many with ADHD, attention is more like sunlight through leaves: scattered and shifting, being pulled in multiple directions. And yet, when something truly resonates or captures interest, they can drop into hyperfocus so completely that time itself seems to bend. Hyperfocus is not unique to ADHD, but it tends to occur more frequently and more disruptively within ADHD populations.

For autistic individuals, focus can be so complete that shifting away feels like loss. Autism is often linked with sustained, deeply focused attention. This can sometimes be so immersive that external circumstances fade into the background. Shifting attention can be difficult, especially when tied to a special interest or when sudden changes in the environment require adaptation.

On the surface, these two portraits may appear distinct. If we look closely, we see the echo: both autistic and ADHD individuals can experience hyper-attention. This crossover can feel confusing, or it can feel like recognition. It tells us something important: the capacity to focus does not cancel out ADHD, just as struggles with focus do not cancel out autism.

AuDHD is not about confinement in a label, but about validation that the overlap itself is real, and that the lives shaped within it are no less whole or worthy of understanding.

When autism and ADHD meet, the result isn’t double the difficulty; it’s a unique choreography of strengths and struggles.

- Executive Functioning: The mind might feel full of ideas but short on sequence. Yet once engaged, focus becomes creative flow.

- Sensory Experience: The world might feel too loud, too bright, or endlessly fascinating and alive with texture and detail. A 2025 meta-analysis confirmed that sensory processing differences are significant in both ADHD and autism and the pattern varies across age and sensory modality.

- Social Connection: There’s often a longing to connect and a simultaneous exhaustion from trying to do it “right.” Underneath it all lies honesty, depth, and an exquisite ability to sense nuance.

- Emotion: Feelings can be tidal, intense, shifting, alive. But this sensitivity also brings empathy, passion, and insight.

No two AuDHD experiences are the same. Each is a distinct rhythm — a personal constellation of perception and energy.

For many people with AuDHD, recognition comes late, if at all. Some are seen as fitting only one category, while others are misunderstood entirely or dismissed as ‘too anxious’ or ‘too sensitive’’ When their experiences don’t seem to align neatly with either autism or ADHD, they may turn the doubt inward: Maybe I’m just not trying hard enough. Maybe I should know how to function by now.

The cost is often invisible. A quiet erosion of self-trust, with real consequences. It may prevent someone from seeking support altogether, leaving them to carry the belief that they either don’t need help, or worse, don’t deserve it. And when support is offered but focused only on ADHD or only on autism, it may not fit. Sometimes, it even amplifies existing struggles, leaving people feeling more unseen.

The impact of this lack of recognition can include:

- Years of self-doubt: questioning one’s own experiences and validity.

- Difficulty accessing appropriate support: resources that don’t fully address the overlap between ADHD and autism.

- A deep sense of isolation: feeling like no one else lives with this combination of challenges and strengths.

- The impact of masking: Camouflaging or masking is widely reported among autistic and AuDHD individuals. On average, it appears more frequently in women and late-diagnosed adults; it is associated with later recognition and emotional exhaustion.

Language matters because it shapes how we see ourselves. Language like AuDHD doesn’t fix everything but can open doors: it allows people to name their experience, reclaim their story and seek the kind of support that honours the whole of who they are.

At Leone Centre our focus is not on fixing, but on understanding. Neurodivergence is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be honoured. For those with AuDHD, therapy can be a space to move beyond labels and into a deeper exploration of what it means to live fully and authentically.

Neurodivergent-affirmative therapy shifts the emphasis from clinical assessment to human connection and practical support. It recognises the complexity of living with both autism and ADHD, and creates space for the ways they converge in everyday life. A psychotherapist’s role is to accompany rather than correct, to listen with curiosity, and to adapt their approach to the unique needs of each individual.

In therapy, this translates to:

- Affirmation, not correction: validating the lived experiences of AuDHD individuals rather than pathologising them.

- Strength-based focus: exploring creativity, resilience, and unique problem-solving.

- Practical strategies: supporting executive functioning, sensory regulation, and emotional wellbeing.

- Relational repair: helping clients navigate friendships, partnerships and family dynamics with more understanding.

- Identity exploration: creating space to integrate autism and ADHD into a coherent sense of self.

Therapy, in this sense, becomes a collaboration: a place where challenges are acknowledged, strengths are celebrated, and a fuller story of self begins to unfold.

When one or both partners have AuDHD, differences in communication, sensory needs, or emotional rhythms can create misunderstandings. Couples therapy provides space to reconnect and better understand each other.

Focus areas include:

- Bridging communication styles

- Navigating sensory and emotional needs

- Rebuilding understanding with empathy

- Honouring neurodiverse perspectives

Whether both partners are AuDHD or one is neurotypical, therapy can help to build balance, compassion, and deeper connection.

Moving from tolerance to celebration begins with how we show up in everyday life. For individuals with AuDHD, the difference is felt in whether they feel managed or truly met, explained away or genuinely understood.

Within supportive spaces, this becomes an invitation to approach one another with compassion and curiosity. In practice, that can look like:

Supporting loved ones in seeking support: Encouraging and walking alongside friends or family members as they access neurodivergent-affirmative support.

Understanding social energy: Masking (the effort to present in ways that feel socially acceptable) requires significant mental energy and can be deeply draining. When that “social battery” runs out, what may appear as withdrawal is often simply the natural recovery needed after prolonged adapting.

Being a safe space: Social energy can be demanding to manage, and for AuDHD individuals it matters deeply to have people who feel like “safe spaces.” These are friends or family who offer unconditional acceptance, where there is no pressure to mask. In these spaces, energy can be conserved, authenticity can breathe, and connection feels restorative rather than draining.

Acknowledging sensory differences: Overstimulation from light, sound, or touch can be overwhelming for autistic individuals, while for those with ADHD the same stimuli may compete for attention. ADHD can also bring sensory-seeking tendencies such as craving movement, novelty, or stimulation rather than avoiding it. For AuDHD individuals, these patterns often overlap, blending sensitivity with seeking. When peers respond with understanding and compassion, it reduces feelings of alienation and makes space for recognising when a change of environment or support might be appreciated.

Letting go of assumptions: Not everyone’s experience will mirror a stereotype. AuDHD opens a window into the many possible ways ADHD and autism can coexist.

Honouring uniqueness: Accepting that the neurodivergent experience is not less valid than the neurotypical one, just different.

When we dismantle “shoulds” and assumptions, AuDHD becomes less about categories and more about embracing the richness of diverse perspectives and experiences.

Living with AuDHD can feel like navigating a world that speaks a different language. But therapy can become a place where your language is honoured and you don’t have to translate or tone yourself down.

When we recognise both autism and ADHD together through neurodivergent affirming support, we move away from the narrative of being “too much” or “not enough.” Instead, we find belonging.

AuDHD sits right in a paradox: a reminder that our minds don’t have to fit neatly into diagnostic shapes to be real, valid, or worthy of care.

Here at Leone Centre, we have many experienced therapists who can offer you that support whether in person in London or online.

Napoleon Near Borodino by Vasily Vereshchagin, 1893.

What is AuDHD? Understanding Autism & ADHD Together

Have you ever asked yourself, “Is it ADHD or autism?” Maybe you see traits of both and feel like no single diagnosis fully explains your experience. You’re not alone.

Autism and ADHD often occur together, a combination known as AuDHD. While research has long recognised the overlap between these two conditions, the concept of AuDHD is still relatively new in clinical settings. It’s also not yet widely understood or formally recognised in diagnostic manuals.

This lack of recognition can make it harder for people with AuDHD to find answers or receive a diagnosis that captures their experience. Many are left navigating years of confusion, misdiagnosis, and feeling misunderstood.

In this post, we’ll explore what AuDHD means, the key symptoms to look out for, and why getting the right diagnosis can make a big difference. By understanding the connection between autism and ADHD, you can begin to navigate life with more confidence, self-awareness, and compassion.

AuDHD is a term used when someone is diagnosed with both Autism Spectrum Condition (ASC) and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). These are both neurodevelopmental conditions. This means autism and ADHD affect how the brain develops and works, especially in areas like communication, attention, and behaviour.

Research suggests a significant overlap: studies estimate that 30% to 80% of autistic children may also meet the criteria for ADHD, and that around 20% to 50% of children with ADHD meet the criteria for autism.

While each condition has its own set of traits, they can overlap in ways that make diagnosis tricky. Understanding how they interact is essential for getting the right support, whether for yourself, a loved one, or someone in your care.

Although autism and ADHD are separate conditions, research shows they share some common ground. Both are linked to differences in brain development and neurotransmitter function, like dopamine. Particularly in brain regions involved in planning, organisation, emotional regulation, and sensory processing.

People with both autism and ADHD might:

- Struggle with impulsivity and emotional outbursts

- Find it hard to filter sensory input like noise or bright lights

- Have trouble with indirect or abstract communication

- Have interest-based attention, meaning they can focus deeply on topics of interest, but struggle with tasks that feel unstimulating

Still, it’s important to note key differences. Autism typically affects how a person communicates and experiences the world. ADHD mainly impacts attention, restlessness, and impulse control.

No, ADHD is not a form of autism, but they do share similarities. They are recognised as distinct conditions with their own diagnostic criteria and neurological profiles.

For example, common symptoms of autism may include:

- Difficulty understanding non-verbal communication (like body language or tone of voice)

- Preference for routine, structure, or predictability (dislike of sudden change)

- Intense interest in specific topics or activities

- Sensory sensitivities ( to lights, sounds, or textures)

- Tendency to take language literally (can have trouble with indirect language, sarcasm or jokes)

- Feelings of overwhelm or shutdown in unfamiliar or high-stimulus environments

In contrast, core ADHD symptoms include:

- Difficulty sustaining focus, especially on tasks they don’t find interesting

- A strong capacity for hyperfocus on topics they find stimulating or meaningful (something that’s often misunderstood)

- Impulsive decision-making or speech (interrupting others or acting without thinking)

- Restlessness or a constant sense of internal activity

- Struggles with planning, organisation, or completing tasks

- Mood swings or difficulty regulating emotions

ADHD often shows up differently in women and girls, which can lead to underdiagnosis or misdiagnosis. While boys may be disruptive or hyperactive, girls often internalise their struggles.

Common signs in women include:

- Anxiety or emotional overwhelm

- Perfectionism and fear of failure

- Overthinking or rumination

- Masking or overcompensating in social situations

This hidden presentation means many women don’t receive a diagnosis until adulthood. (You can read more about ADHD in women in our dedicated blog post.)

In kids, symptoms are usually more visible compared with adults. For example:

- ADHD might show up as excessive talking or constant movement.

- Autism may present as difficulty making friends or needing strict routines.

In adults, the signs are often more subtle. Hyperactivity may look like constant mental restlessness. Adults with autism might appear “socially competent” but only because they’ve learned to mask their traits. This often comes at a cost to their mental health.

When someone has autism and ADHD, these traits can interact in complicated ways. People with both autism and ADHD can experience a wide range of challenges that go beyond either condition alone. For example, someone might hyperfocus on a special interest (autistic trait) but still struggle to complete tasks due to distractibility (ADHD trait).

Here are some common AuDHD experiences:

- Sensory overload + impulsivity: Reacting quickly or strongly to overwhelming sensations

- Hyperfocus vs. distraction: Getting stuck on one task, then struggling to switch to another

- Social challenges: Misreading cues while also interrupting or oversharing

- Emotional volatility: Feeling emotions deeply and struggling to regulate them

- Daily life difficulties: Trouble with planning, prioritising, or remembering tasks

- Heightened sensory responses: Feeling easily overwhelmed by everyday sensory input, such as clothing textures, background noise, or lighting

- Emotional sensitivity and reactivity: Experiencing strong emotions that can feel difficult to regulate, often leading to emotional highs and lows

- Mental fatigue and burnout: Becoming exhausted from masking traits, managing competing demands, or navigating environments not suited to neurodivergent needs.

Women with AuDHD often don’t match the typical (often male-based) diagnostic criteria. Instead of being outwardly hyperactive, they may:

- Appear highly anxious or perfectionistic

- Mask their difficulties in social settings

- Experience chronic exhaustion or burnout

- Struggle silently with routines, organisation, or sensory issues

Because their struggles are less visible, women are often overlooked or misdiagnosed. Sometimes with anxiety, depression, or personality disorders instead of the underlying neurodevelopmental conditions.

Recent research has drawn attention to this gender gap in diagnosis. For decades, neurodivergent women and girls have been left behind. Facing long waits, limited support, and a lack of recognition. As more women begin to identify with both ADHD and autism, it’s clear that we need more inclusive assessments and better understanding of how these conditions show up across genders.

Although autism and ADHD can look similar, their core differences matter:

- Autism is mainly about how someone communicates and experiences the world.

- ADHD is about how someone regulates attention and impulses.

The overlap between traits can be confusing. For example, difficulty focusing could be due to ADHD, or it could stem from autistic sensory overload. That’s why professional assessments are key to understanding the full picture.

If you’re unsure where to start, our psychiatrists can offer an initial consultation to decide whether to begin with an ADHD or autism assessment. Contact us to find out more.

AuDHD is not formally recognised as a condition in clinical guidelines like the DSM-5 or ICD-11. However, research and recognition of AuDHD is growing. More clinicians are starting to recognise that people diagnosed with both ADHD and autism require unique care. Clinicians may use a combination of evidence-based approaches to assess for autism and ADHD separately while considering how traits interact, such as:

- Clinical interviews

- Standardised questionnaires

- Behavioural observations

- Input from family or school records

- Medical and developmental history

Because symptoms of autism and ADHD can mimic or mask each other, it’s important to work with a clinician who understands both. They’ll look at how traits interact, not just how symptoms show up in isolation. For example, impulsive behaviour could be driven by ADHD, or it might be a sensory-seeking trait linked to autism.

If you suspect you have ADHD with autism, seeking a specialist familiar with both conditions is essential. You can explore more about ADHD assessments and the evaluation process here.

You can also begin with our free ADHD screening test for adults.

Assessment for autism and ADHD (AuDHD) often includes a clinical interview accompanied by questionnaires and information from people who know you well.

The assessment process may involve screening questionnaires such as the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) and ADHD rating scales. Additionally, professionals may conduct direct behavioural observations and cognitive testing to assess attention regulation, impulsivity, and social interaction challenges. These tests help determine if an individual fits the profile of AuDHD and rule out other possible explanations for their symptoms.

If you’re considering an assessment, our team can support you through the process. Speak with our friendly medical secretaries today, and they can help match you with a clinician who specialises in both ADHD and autism.

Life with AuDHD can feel like a rollercoaster. Sometimes you might feel hyperfocused and energised, other times you can feel completely overwhelmed or shut down.

But understanding your brain can change everything. Studies show that people with autism are much more likely to also have ADHD, and vice versa people with ADHD are more likely to have autism. Yet many still go undiagnosed for years.

Knowing you have AuDHD helps you get the right support and make choices that actually work for you, instead of constantly trying to fit into a neurotypical mold.

People with ADHD and autism often face a unique set of hurdles in everyday life. Common challenges can include:

- Being easily overwhelmed by everyday tasks and challenges

- Struggling to keep up with routines or schedules

- Burnout from masking or “performing” socially

- Avoidant coping mechanisms like fantasy or escapism

Despite the daily struggles, AuDHD individuals also bring exceptional strengths to the table. Their unique perspective often leads to creative problem-solving and out-of-the-box thinking. Having a deep focus and passion for specific interests often allows them to become experts in their field. Emotional sensitivity (often seen as a challenge) can also lead to a powerful form of empathy.

Understanding the difference between autism and ADHD can clarify how these strengths emerge differently. Recognising your unique abilities is as vital as acknowledging your struggles.

AuDHD burnout can be intense, prolonged, and deeply misunderstood. AuDHD burnout is beyond just feeling tired. It’s a deep physical and emotional crash caused by chronic stress and sensory/emotional overload. This kind of burnout arises from the effort of masking symptoms, managing autism and ADHD symptoms, and navigating a world not built for neurodivergent minds. Signs of burnout can include:

- Fatigue

- Loss of motivation

- Increased anxiety or depression

- Emotional numbness or detachment

Recovery means more than just taking a break. It means making sustainable changes, like reducing demands, setting boundaries, and building a life that works with your brain, not against it.

Managing AuDHD starts with self-awareness. Once you understand how your traits show up, you can build systems that work for you.

Here are a few strategies that can help:

- Mindfulness and grounding: Helps with emotional regulation and sensory overload

- Physical activity: Eases hyperactivity and improves focus, particularly yoga, walking, or strength training

- Sensory tools: Noise-cancelling headphones, weighted blankets, or fidget tools

- Visual supports: Calendars, reminders, and visual schedules for planning

- Tailored routines: Create structures that support your energy and focus levels, including rest!

Most importantly, give yourself permission to do things differently. You’re not broken! Your brain just works differently.

There’s no “one-size-fits-all” approach, but many people with AuDHD benefit from:

- Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) tailored to neurodivergent needs

- Coaching or mentoring for executive functioning

- Medication for ADHD, if appropriate (though responses vary if you’re also autistic)

- Occupational therapy to help with sensory and practical challenges

At the London Psychiatry Clinic, we offer assessments and support tailored to people navigating both autism and ADHD. You can book an ADHD assessment or take a free adult ADHD test to get started.

Living with AuDHD can be complicated, but it doesn’t have to be confusing. With the right understanding, support, and tools, you can manage your challenges and celebrate your strengths.

- AuDHD refers to the co-occurrence of autism and ADHD in one person.

- These conditions can overlap and interact in unique ways.

- Recognising both challenges and strengths is essential to building meaningful support.

- If you think you might have AuDHD, start with a free ADHD test or speak with our friendly team to find out about getting an assessment.

Traditional ASMR Full Body Medical Exam (Scalp Exam, Stethoscope, Eye Tracking) 🩺 ASMR Roleplay

The Blue Yeti is back, and ready for a traditional ASMR exam (with the added bonus of having a 2nd camera on my laptop typing). We’ll start at the scalp (with some fuzzy windscreen sounds) and work down to the lower extremities. Skin inspection, sticky stethoscope, lots of eye testing, whole bunch of palpation; we’ve got a whole lot going on.

Typing Your Information: 00:00 – 02:14

Taking a Peek at Your Scalp: 02:14 – 04:54

Inspecting Skin with Magnifying Glass: 04:54 – 06:56

Facial Palpation Exam: 06:56 – 08:34

Sinus Check with Face Tapping: 08:34 – 09:35

Lymph Node Check: 09:35 – 11:36

Carotid & Temporal Artery Auscultation: 11:36 – 13:19

Inspecting Your Eyes: 13:19 – 14:59

Pupillary Response & Eye Tracking: 14:59 – 20:08

Typing Notes: 20:08 – 21:54

Nose/Mouth/Throat Exam: 21:54 – 25:24

Ear Exam: 25:24 – 28:48

Listening to Heart & Lungs: 28:48 – 32:43

Abdominal Auscultation: 32:43 – 34:09

Chest & Abdomen Palpation: 34:09 – 37:37

Reflexes & Extremities: 37:37 – 44:35

Typing & Dictating Notes: 44:35 – 46:00

Wrapping up the Exam: 46:00 – 46:18

Outro with Fuzzy Windscreen Stroking: 46:18 – 47:24

Triggers include: typing, soft speaking, whispering, scalp exam, fuzzy windscreen sounds, magnifying glass, skin inspection, face touching, palpation, sticky finger sounds, crinkly cling wrap sounds, narrating actions, dictating notes, guided deep breathing, sticky stethoscope, eye exam, light triggers, eye tracking, accommodation reflex test, ear exam, and reflex testing.

Hope y’all enjoy, have a whale of a day! 🙂

xx Calliope

Now listening to Three O’Clock High by Tangerine Dream and Slide It In by Whitesnake…

On Pacific Street in Downtown Vancouver. Summer of 2017.

Pacific Street is a vibrant east-west thoroughfare in the heart of downtown Vancouver, British Columbia, running parallel to the waterfront and serving as a key connector between the West End, Yaletown, and False Creek. It’s part of the city’s iconic seawall network, blending residential luxury, commercial energy, and recreational access. It’s a sought-after address for high-end condos and urban living, with a walk score often exceeding 90 due to its proximity to beaches, transit, and amenities.

Pacific Street stretches approximately 2 km through downtown, from the edge of Stanley Park in the west (near English Bay) eastward to Main Street, skirting the southern boundary of the West End and transitioning into Yaletown. It runs parallel to Beach Avenue and Davie Street, offering easy access to the Vancouver Seawall—a 28 km pedestrian and cycling path. It borders the upscale West End (residential and beachfront) to the north and the bustling downtown core/Yaletown to the south. Key intersections include Pacific & Hornby (luxury towers) and Pacific & Burrard (near Sunset Beach). Served by multiple transit options, including the SkyTrain’s Canada Line (Vancouver City Centre station nearby) and bus routes along Davie and Beach. It’s a short walk to the Vancouver Convention Centre and ferry terminals.

Named in the late 19th century during Vancouver’s early urban planning, Pacific Street emerged as a residential and commercial corridor amid the city’s post-1886 Great Fire rebuild. In the 1960s–1970s, it became part of broader downtown revitalization efforts, influenced by the development of Pacific Centre mall (opened 1974), which reshaped nearby Granville and Georgia Streets but indirectly boosted Pacific’s accessibility. Just north at Granville & Georgia, Pacific Centre Mall, a 578,000 sq ft shopping hub (built 1971–1973), was Vancouver’s largest indoor mall upon opening. It displaced heritage buildings but integrated with SkyTrain via skybridges to Hudson’s Bay and Vancouver Centre Mall. Today, it’s anchored by Holt Renfrew and features over 100 stores (e.g., Apple, Sephora, Tiffany & Co.), drawing 22 million visitors annually. A 2020s redevelopment added a glass-domed Apple Store at Howe & Georgia. Pacific Central Station (1150 Station St, near Main & Terminal Ave) is a short walk east. This 1919 Beaux-Arts railway terminus (built for $1 million) features granite, brick, and andesite facades with Doric columns and ornate interiors (skylights, mouldings). Originally for Canadian Northern Pacific Railway, it’s now VIA Rail/Amtrak’s western hub, with bus services added in 1993. It holds historical ties to Black Strathcona porters. The street reflects Vancouver’s shift from industrial port to modern condo haven, with 1970s towers giving way to 2020s luxury builds emphasizing seawall views.

The 501 (501 Pacific St) is a 33-story tower with 295 units, completed recently. It steps from False Creek and Sunset Beach. Amenities include gyms and rooftop decks; recent sales show competitive pricing (e.g., units sold $30K–$75K under asking in 2025). The Pacific by Grosvenor (889 Pacific St) is a 39-story, 221-unit development (2021), featuring Italian Snaidero cabinetry, Dornbracht fixtures, and deep balconies mimicking cloud textures. Units range from 1–4 bedrooms; a recent penthouse sold $75K under asking in October 2025. The Californian (1080 Pacific St) is a 7-story, 84-unit concrete building (1982) with rooftop decks, saunas, hot tubs, and recent upgrades (new plumbing, elevators). Walk score: 92; near Sunset Beach. 1215 Pacific St is a 5-story, 50-unit mid-rise (1977) with underground parking and storage, in the West End near Bute St. Lined with cafes, boutiques, and seawall access points, Pacific Street is a hub for cycling/jogging, with proximity to English Bay, Stanley Park, and Granville Island via bridges. The area supports an active lifestyle, with gyms, spas, and markets within blocks. Upscale yet accessible—think sunset strolls, yacht views, and quick hops to downtown shops. Real estate is hot, with 2025 sales reflecting Vancouver’s densification trend.

High walkability (92+ score); bike lanes and seawall paths abound. Parking is limited—use underground spots in condos or nearby lots. Buses run frequently; SeaBus is a 10-minute walk. Pacific Street embodies Vancouver’s “live-work-play” ethos, evolving from 1970s mall-driven commerce to 2020s luxury residential.

AuDHD Burnout — Freelife Behavioral Health

Living with both autism and ADHD means running two operating systems at once—always switching windows, always patching bugs. It’s exciting, creative, and exhausting. Sooner or later, many of us hit a wall known as AuDHD burnout. Understanding what it is—and how it differs from other kinds of exhaustion—can be the first step toward healing.

What Does AuDHD Burnout Feel Like?

Picture a laptop with too many tabs open. The fan whirs, the screen lags, and then everything freezes. AuDHD burnout feels similar:

- Brain fog so thick you forget what you’re saying mid-sentence.

- Sensory spikes—lights sting, sounds jab, fabrics itch.

- Executive paralysis—dishes pile up, emails go unanswered, even fun hobbies feel heavy.

- Mood swings—irritation, shame, or flat-line numbness.

Because AuDHD blends two neurotypes, the crash can be dramatic. Your ADHD side still craves novelty, while your autistic side begs for quiet. Caught between “do everything” and “do nothing,” it makes sense that you may short-circuit.

What Does Autistic Burnout Feel Like?

Autistic burnout shares some traits with AuDHD burnout, but there are differences:

- Withdrawal—social, emotional, sometimes physical.

- Loss of skills—speech slows, coordination slips, routines collapse.

- Extreme fatigue—sleep can’t fix it, coffee can’t mask it.

Where autistic burnout often follows long stretches of masking or sensory overload, AuDHD burnout layers on ADHD’s executive struggles and impulsive guilt spirals. You’re not just tired—you’re torn.

How Does AuDHD Differ from ADHD?

ADHD alone is mostly about attention regulation, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Autism centers on sensory processing, social communication, and need for predictability. With AuDHD you get both sets of wiring:

- Your mind races (ADHD) yet loves deep focus on niche interests (autism).

- You chase stimulation (ADHD) yet overload quickly (autism).

- You miss details (ADHD) yet notice tiny pattern shifts (autism).

Because these traits clash, everyday life demands extra energy. That constant self-management is why AuDHD burnout can appear sooner and last longer than typical ADHD exhaustion.

What is the Burnout cycle of Autism?

Researchers describe a loop: Accumulation → Breakdown → Recovery → Adaptation.

- Accumulation – weeks or months of masking, sensory stress, and social effort build up.

- Breakdown – energy tank hits empty; shutdowns or meltdowns occur.

- Recovery – reduced demands, quiet environments, special interests, and rest.

- Adaptation – new boundaries, tools, and support are added.

With AuDHD burnout, this cycle speeds up. ADHD impulsivity pushes you to keep saying “yes” even when your autistic battery is blinking red. The breakdown can arrive with little warning, and recovery may require stricter boundaries around tasks, noise, and social commitments.

Why Queerness Matters

Queer people with AuDHD juggle yet another layer: navigating identity in spaces that may not understand them. Living in multiple margins means more masking, more micro-aggressions, more vigilance. Pride festivals can be affirming but also loud, crowded, and schedule-breaking—perfect storm conditions for AuDHD burnout.

Community helps, but only if it’s accessible. Quiet queer meetups, sensory-friendly dance nights, and online support groups can give relief without overload. Therapy that respects neurodivergence and queerness can turn survival into sustainable self-care.

Five Ways to Break the Burnout Loop

- Audit sensory input: Carry earplugs, adjust lighting, choose soft fabrics. Small tweaks can prevent big crashes.

- Use interest-based breaks: Hyperfocus isn’t the enemy—use it. Ten minutes watching a favorite analysis video or arranging a playlist can reset your brain.

- Block off recovery time: Treat rest as a standing appointment, not a reward. Color-code downtime in your calendar the way you would a meeting.

- Externalize tasks: Sticky notes, phone alarms, or body-double work sessions keep ADHD drift in check so it doesn’t pile stress on your autistic need for order.

- Seek affirming therapy: A clinician who gets AuDHD, queer identity, and racial or cultural context can help you design realistic routines instead of prescribing generic “self-discipline.”

I Don’t Like These Remasters

Now reading Monuments Of Civilization: Rome by Filippo Coarelli…