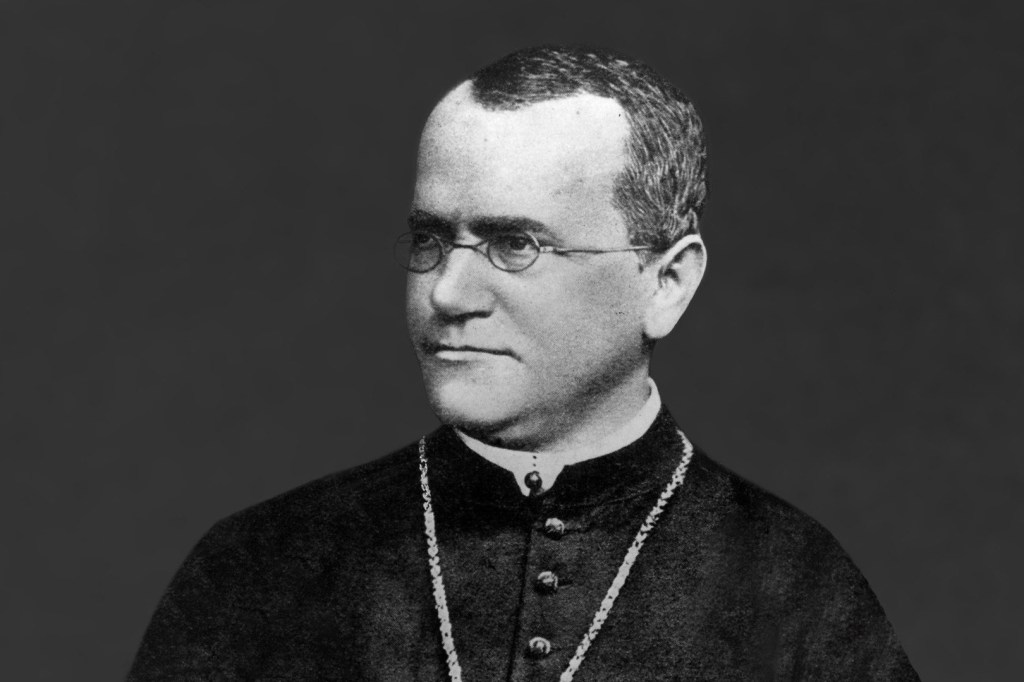

Gregor Mendel (1822-1884)

The Austrian botanist Gregor Johann Mendel was a genius of the plodding, hardworking, single-minded sort – a genius for whom discovery was, as Thomas Edison put it, one percent inspiration and 99 percent perspiration. He was not a playful, intuitive genius like Picasso. (The great painter once said, “I do not seek — I find,” an attitude that describes many of the men and women we now think of as geniuses.)

Mendel “toiled, almost obsessively, at what he did. But still he had that extra 1 percent, that inspiration that helped him see his results from a slightly different angle. It was this flash of insight that allowed Mendel to perform a feat of genius: to propose laws of inheritance that ultimately became the underpinning of the science of genetics” (Henig, 2001, p. 6).

According to Henig (2001) it was Mendel’s non-heroism that allowed him to do the patient, thorough work through which his genius emerged (p. 168). A science was named in his honor: Mendelian genetics. High-functioning autism/Asperger Syndrome would be highly useful in this kind of plodding work, and this chapter presents the evidence that Mendel displayed this condition.

Mendel made the first tentative step towards a concept that would not be fully elucidated for another 50 years: the difference between phenotype (the way something looks) and genotype (the particular combination of genes that explains those looks) (Henig, 2001).

Life History

Mendel was born on July 22, 1822, near Udrau, in Austrian Silesia. His father, a farmer, did some experimental work with grafts to create better fruits. Mendel entered the Augustinian cloister at Briinn, and was ordained a priest. Having studied science at Vienna, he returned to Briinn and later became abbot. He studied plant variation, heredity, and evolution in the monastery’s garden, particularly in pea plants. (It is interesting that many adults with autism work well in gardens; e.g., at Dunfirth in Ireland, people with autism live and work at activities such as organic vegetable growing that are intended to foster their growth and development.)

Mendel died at Briinn in January 1884, from Bright’s disease (inflammation of the kidneys). Later, he was heralded as the father of genetics. During his years of anonymity, the priest was fond of telling his friends, “My time will come.”

Work

According to Henig (2001), Mendel “observed that traits are inherited separately and that characteristics that seem to be lost in one generation may crop up again a generation or two later, never having been lost at all. He gave us a theoretical underpinning for this observation, too: he believed the traits passed from parent to offspring as discrete, individual units in a consistent, predictable, and mathematically precise manner” (p. 7). Sixty years after his death, a friend stated, “Not a soul believed his experiments were anything more than a pastime, and his theories anything more than the maunderings of a harmless putterer” (Henig, 2001, p. 164). During the winter, Mendel spent as much time as he could in the monastery library, doing meticulous work. His relationship to peas was probably similar to that of other persons with autism to numbers.

Social Behavior

Mendel was essentially homebound for his first forty years. In one photograph he is “standing in the precise middle of the group and looking off somewhere past the photographer’s left shoulder” — he stands “erect and alone” (Henig, 2001, p. 121).

Mendel was a very shy person, with major peer and relationship problems. He had a naturally reticent personality: a friendly reserve with an underlying privacy. He was unable to do the most basic work that priests were required to do and was not in good health. He took to bed with a mysterious illness. Abbot Napp, the head of the monastery, stated that he was “seized by an unconquerable timidity when he has to visit a sick-bed or to see anyone ill or in pain. Indeed, this infirmity of his has made him dangerously ill” (Henig, 2001, p. 37).

When trying to do some teaching, he panicked and performed poorly at a teaching assessment that involved both an oral and a written examination. Professor Kanner, who examined his geological essay, described it as arid, obscure, and hazy, his thinking as erroneous, and his writing style as hyperbolic and inappropriate. Clearly Mendel had been an autodidact. Six years later he again tried to pass the certificate examination but panicked again and failed. According to Henig (2001), he was relegated for the rest of his career to the rank of uncertified substitute teacher.

Narrow Interests/Obsessiveness

As a boy Mendel was a disappointment to his father because of his reluctance to get out of bed. Mendel was attracted to book learning and joined the local monks.

Henig (2001) referred to a “one-track, simmering genius that had a chance to explode only years later, when the twin stars of intuition and accident were momentarily aligned in Mendel’s favor, providing him an insight into the mystery of inheritance that few but he were prepared to understand” (p. 22). Henig thought that as a young man Mendel was probably eager, driven, and scientifically voracious. Nevertheless, he had interests other than experimental science: He became the official “weather watcher” for the city of Briinn and recorded meteorological readings every day. The fame that he longed for would come to him in his lifetime primarily as a local meteorologist. He was a skilled chess player (persons with autism are often interested in chess); he kept bees and gathered honey. He regarded his bees as his “dear little animals.”

According to Henig:

Mendel was also forever amusing himself with scientific and mathematical ideas that had nothing to do with plants. On the back of a draft of one of his dozens of church-tax missives, he scribbled lists that showed that, even in the midst of administrative tasks, he set himself new intellectual challenges. One of the most intriguing was a list of common surnames. Using several directories — the Military Year Book of 1877, the register of transporters, the register of bankers, a barristers’ year book — Mendel collected more than seven hundred names, which he arranged in different ways in an apparent attempt to spot some sort of pattern. First he placed them in alphabetical order, then he grouped them according to meaning. (2001, p. 165)

Mendel’s experimentation with peas was tedious work: In the autumn of 1857 alone, he had to shell, count, and sort by shape more than 7,000 peas, and that was just for one experiment, involving crosses between round and angular peas (Henig, 2001, p. 81). By the time he finished his work, seven years after he began, Mendel had conducted seven versions of this experiment, seven different monohybrid crosses, designed to look at plants that varied in only a single trait (shape first, then color, then height). By the time he had completed this succession of crosses, re-crosses, and backcrosses, he must have counted a total of more than 10,000 plants, 40,000 blossoms, and a staggering 300,000 peas. Virtually no one except a person with autism could do this.

Henig (2001) noted that Mendel applied his passion for counting almost indiscriminately to everything in his own little world. He counted not only peas but weather readings, students in his classes, and bottles of wine purchased for the monastery cellar. People with high-functioning autism are fascinated by numbers.

After Mendel became abbot of his monastery, he engaged in an obsessive letter-writing campaign against the new “monastery tax,” which he continued until his death.

Routines/Control

“Monastery life was a balm to Mendel. Its regularity provided ease and comfort to a man who had spent his first twenty-one years in a thicket of uncertainty” (Henig, 2001, p. 25).

The orangery became his favorite place in the monastery. This is reminiscent of Ludwig Wittgenstein writing his philosophy in the warm botanic gardens in Dublin. He furnished the orangery with “a game table for playing chess; an oak writing table; six rush-bottomed nut wood chairs; and a few paintings. In his last years, when as abbot he could use the monastery’s grandest rooms, he still spent his time in the orangery … working through the mathematical, biological, and meteorological problems that vexed and intrigued him all the days of his life” (Henig, 2001, p. 65).

Language/Humor

Mendel, even to the end of his life, had a waggish and somewhat mischievous sense of humor, and “collected good jokes the way Darwin collected barnacles” (Henig, 2001, p. 163). He once upset the local bishop by saying, in what he thought was a whisper, that the bishop possessed “more fat than understanding.” He would “walk slowly among the plants, which he liked to call his ‘children’ to get a reaction from visitors who did not know about his gardening experiments. “Would you like to see my children?’ the priest would ask. Their startled and embarrassed faces were always good for a chuckle” (Henig, 2001, p. 116).

Anxiety/Depression

Mendel became paranoid later in his life, just like Isaac Newton, and was suspicious of everyone, even his fellow monks, whom he thought to be “nothing but enemies, traitors and intriguers” (Henig, 2001, p. 162).

Mode of Thought

Mendel became interested in combination theory, which describes the relationship among the objects in a group arranged in any predetermined way. Henig (2001) saw this belief in combination theory as a mark of Mendel’s genius: “Throughout history, some of the most creative minds have been those capable of maintaining two different mental constructs of the world simultaneously and applying the principles of one model to problems in the domain of the second” (p. 54).

The day he died, the local Natural Science Society heard a eulogy that referred to his “independent and special manner of reasoning” (Henig, 2001, p. 166).

Appearance

Henig (2001) quoted an acquaintance who described Mendel as “a man of medium height, broad-shouldered … with a big head and a high forehead, his blue eyes twinkling in the friendliest fashion through his gold-rimmed glasses. Almost always he was dressed, not in priest robes, but in the plain clothes proper for a member of the Augustinian order acting as schoolmaster — tall hat; frock coat, usually rather too big for him; short trousers tucked into topboots.” His dress “bespoke his decorum and modesty; he was out in the world, but always a cleric” (p. 90). It is interesting that he is supposed to have had a big head: 50% of people with autism have big heads. This may be due to less pruning of cells early in life but may lead to a greater capacity to carry out mathematical calculations. When he walked, according to an acquaintance, he looked straight in front of him.

Conclusion

Mendel showed many of the criteria for Asperger Syndrome, particularly obsessiveness, social impairment, and love of routine. He also had the interest in counting, classifying, and mathematical calculation that is quite typical of the syndrome.

- Michael Fitzgerald, Former Professor of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry

Just finished watching The Flame (1947) and Cloud Waltzing (1987)…

Just finished watching Avatar: The Way Of Water (2022) and Weapons (2025)…

England as the Workshop of the World

I will continue to quote from ‘Paths of Fire: An Anthropologist’s Inquiry into Western Technology’ (1996) by Robert McCormick Adams. The following quote is from the fourth chapter, which is titled England as the Workshop of the World. “The onset of the Industrial Revolution, while an epochal transformation in any longer view, involved no sudden or visible overturning of the established order. Many contributory streams of change had converged and unobtrusively gathered force during the first two-thirds or so of the eighteenth century. Leading elements of technological change presently began to stand out – in engines and applications of rotary power, in the production of iron and steel, and most importantly in new textile machinery. But their sources and significance lay primarily in interactions with a wider matrix of other, earlier or contemporaneous changes. As we have seen, these other changes were largely of a non-technological character. While highly diverse, the most important can be briefly summarized. Among them were the consolidation of large landholdings and the commercialization of agriculture; the widening web of international trade; unprecedented urban growth; rising, increasingly differentiated internal demand and the development of markets to supply it; intensified applications of oversight and discipline in prototypes of a factory system; growing concentration of wealth and the socially sanctioned readiness to invest it in manufacturing; and, not least, the discovery of common interests and meeting grounds by inventors, engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs. Not as anyone’s conscious intention, it was out of such diverse elements – and the even broader and more diffuse shifts in cultural predispositions that underlay many of them – that an era of profound irreversible change was fashioned. This chapter will sketch the main outlines of how it happened and the role that technology occupied along the leading edges of change. But no less important than England’s taking of commanding leadership was how it slipped away in the later nineteenth century. We will discover that this was no internally determinate, quasi-biological cycle of youthful vigor, maturity, and decline. It mostly had to do instead with the diffusion and further development of core features of the Industrial Revolution itself. External competitors could quickly assimilate the English example while escaping some of its natural shortcomings as a pioneer. Uncapitalized, the term industrial revolution denotes a significant rise in manufacturing productivity and an ultimately decisive turn in the direction of industrial growth, anywhere and at any time. So used, it applies to all of the sequential phases of modernization on a technological base that, at a still-accelerating pace, have cumulatively transformed the world since the late eighteenth century. On the other hand, when stated as the Industrial Revolution, it is widely used, and is used here, to refer specifically to the founding epoch of machine-based industrialization in England that began around 1760 and lasted there for something less than a century. There is no dispute that this was a time of sustained, cumulatively substantial change. Within a human lifetime of seventy years or so England moved forward without serious rival into the status of “workshop of the world.” As such, it came not only to dominate world trade but to transport much of that trade in its ships. Industrialization directly and profoundly altered the fabric of life for many, drawing a rural mass not only into urban settings but into factories and other new, urban-centered modes of employment. Population, having risen only slowly until late in the eighteenth century, turned sharply upward by the early nineteenth and rose by 73 percent (from 10.5 to 18.1 million) between 1801 and 1841. Markets proliferated, and popular dependence on them both deepened and widened. Travel beyond one’s local community or district came within an ordinary wage earner’s reach. National income rose precipitately, although the significance of this for any notion of “average” income or well-being is undermined by growing inequities of distribution. Important as these largely material changes were in their own right, we must not overlook their intersections – but also their differences – with others in the realm of ideas. Introduced in the wake of the American and French Revolutions were new aspirations for individual rights, equality before the law, and widened political participation. Echoing great themes of popular unrest that had risen to the surface in the seventeenth century and never been completely submerged, they gave ideological form and content to the protests of working-class movements as they emerged to meet the new challenges of the factory system. Similarly energizing were the great nonconformist religious movements that from the mid-eighteenth century onward began to challenge the established Church of England. And differentially directed against each of these streams was a backlash, chronicled at length by Edward Thompson who saw it as a ‘political counter-revolution,’ that continued for four decades after 1792. The growing commercial role of coal as a vital resource is one of the central economic trends of the seventeenth century. Without assured, relatively cheap access to this new fuel, London, growing by almost 45 percent in the last half of the seventeenth century, almost certainly could not have become the largest city of Europe. During that period, a growing demand for coal for industrial use was simultaneously added to its already well established reliance on coal for domestic consumption. As a result, by 1700 British production had climbed to the level of 2.5-3 million tons annually, estimated to have been “five times as large as the output of the whole of the rest of the world.” Half of the entire tonnage of the British merchant fleet was by then engaged in the coal trade. Huge forces were at work here, even though the linear succession of their effects is far more anonymous and difficult to document in any way than the line of scientific advances that laid some of the groundwork for – but stopped short of – the Newcomen engine. It is certainly in this economic context, I submit, that we must look for the stimulus to the steam engine as an epoch-making invention. With almost equal certainty, we must assume the existence of a wide, diffuse, relatively unknown circle of entrepreneurs, experimenters, skilled mechanics, and would-be inventors. This, and not the more elevated circle of gentlemen in the Royal Society, was Newcomen’s proper setting and source of creative sustenance. “In round numbers,” E. A. Wrigley estimates that London “appears to have grown from about 200,000 in 1600 to perhaps 400,000 in 1650, 575,000 by the end of the century, 675,000 in 1750 and 900,000 in 1800.” Across the span between the mid-seventeenth and mid-eighteenth centuries, in other words, London had risen from housing about 7 percent to an unprecedented 11 percent of England’s total population. Lacking effective provisions for sanitation or for the prevention and treatment of many endemic and epidemic diseases, London of course had a significantly higher mortality rate than the country at large. By all reckonings, Watt’s multiple improvements in the Newcomen engine ultimately came to occupy a place at the very core of the Industrial Revolution. His first (1769) patent added a separate condenser and made related changes greatly to increase its pumping efficiency, immediately making possible the deeper and cheaper mining of coal. Later patents in the early 1780s provided vital adaptations of it for driving machinery of all kinds, stimulating more continuous operations and an expansion of scale in virtually every industry. The city of Manchester, widely regarded as the first citadel of the Industrial Revolution, powered its largest spinning and weaving factories with Boulton & Watt engines. Fundamental as Watt’s contributions proved to be, it is important to recognize that, even with Boulton’s joint efforts, their commercial success was neither immediate nor assured. The economy and reliability of his steam engine as a power source took time to establish, and waterwheels continued for many years to provide a highly competitive alternative. As has often been the case, cumulative smaller improvements in older and competitive technologies substantially delayed the adoption of the new and seemingly superior one. In particular, advances in waterwheel design for which Smeaton had been responsible greatly extended the aggregate reserves of water power available to accommodate new industrial growth. Dominating popular understanding of the Industrial Revolution is an impression of sustained, transformative growth. In the preceding account also, attention has been focused on technological and economic advances. But what has been said may leave the sense of a rising tide that, if at somewhat different rates, surely was managing to raise all boats. Is this impression accurate? The gross disproportion in the levying of the tax burden might suggest otherwise. It had almost doubled by 1815 (to more than 18 percent) as a share of national income, as a result of war expenditures that had spiraled upward from the time of the American Revolution. Excise duties on domestically produced goods and services were principally called upon to sustain the increase. Although they also impacted on the cost of decencies and luxuries for those with discretionary incomes, these duties fell more heavily on price-inelastic necessities for factory workers. By contrast, with relatively minor and temporary exceptions, “There was no effective tax on wealth holders throughout the period.” How disproportionate, in fact, were the respective allocations of the benefits of growth to different groups within British society? What are we to make of the great waves of popular protest, including especially the Luddite movement that aimed at the destruction of textile machinery in the second decade of the nineteenth century, and the working-class movement for parliamentary reform in the late 1830s and 1840s that was known as chartism? Were they only transitory episodes of conspiratorially incited unrest, as was repeatedly proclaimed by the courts and aristocracy in suppressing them with considerable severity? Or were they instead manifestations of deep-seated, broadly felt grievances over declining living standards and a loss of security that was in increasingly sharp contrast with growing national wealth? In impressive detail, Edward P. Thompson’s massive work on The Making of the English Working Class (1963) argues the “pessimistic” case for what he regards as the preponderantly negative impact of the Industrial Revolution on England’s working people. Beyond this, Thompson also records the repressive legal climate with which virtually any form of individual or organized speech or action to obtain redress of political or economic grievances was received. Drawing upon “political and cultural, as much as economic, history” across the half-century or so after 1790, he argues that this forged a working class able self-consciously to identify and struggle for its own strategies and interests. That outgrowth of resistance and self-discovery was, for him, “the outstanding fact of the period.” But Thompson’s emphasis on the centrality of class formation is sharply disputed by some other authorities and is, in any case, not one on which it can be said that any consensus has emerged. More immediately relevant to our concerns is a further judgment reached by Thompson. The working class did not come into existence, he insists, as a spontaneously generated response to an external force – the factory system, or the technological advances of which factories were an outcome. That would imply that the class itself was composed of “some nondescript undifferentiated raw material of humanity,” lacking common, historically derived aspirations and identifying symbols of its own solidarity. “The working class made itself as much as it was made.” It is strongly implied in most contemporary accounts that there was widespread aversion to factory employment. Those whose skills made them members of the “aristocracy of labor” no doubt constituted an at least partial exception. For the mass of less skilled and unskilled workers, however, factory jobs may have been seen as the only alternative following loss of rural livelihoods as a result of enclosures and the consolidation of smaller workshops. No doubt people often entered the mills in the (usually illusionary) conviction that such work was only a temporary expedient and hence could be briefly tolerated. Symptomatic of this is a textile factory owner’s complaint in the 1830s about the “restless and migratory spirit” of his mill workers. Long, closely supervised shifts were, after all, a starkly unpleasant departure from periodically demanding but on the whole far more intermittent agricultural labor schedules. Moreover, the factories themselves often bore a disturbing resemblance to parish workhouses for pauper women and children – from which, in fact, not a little of the early factory labor force had been involuntarily recruited. The pauper apprenticeship system, barbarous as it was in terms of “children working long hours for abysmal wages,” was in any case short-lived. The need for it was greatest prior to the general shift of spinning factories to the more advanced Crompton’s mules driven by steam power. For as long as the availability of waterpower was a requirement, the necessary location of some mills in remote settings had isolated them from the rapidly growing potential work force that was congregating in the new industrial cities. Some, but not all, of the deterioration that had occurred in the material conditions of life can reasonably be laid at the door of the conscious discretion of industrial owners and managers. That applies, for example, to the sometimes almost unbelievably harsh conditions of exploitation of child labor that Thompson cites, and perhaps to some deliberate manipulation of skilled and unskilled, male and female groups of factory operatives in order to depress wages by maintaining an unemployed but dependent reserve. We must not forget that the science of public health was in its infancy. The effects of urban congestion on endemic and epidemic diseases were only beginning to be understood. No body of experience made it possible to gauge the combined effect of malnutrition, pollution, and extended hours of daily employment on expectant mothers and especially on the health and growth of children. It has remained for late twentieth-century analysts to discern such indirect consequences as declining human stature, and persistent high rates of infant mortality, rising illiteracy, precisely in the latter part of the Industrial Revolution when the incomes of male factory operatives are supposed to have risen. The general impression thus is left that there was little or no improvement in living standards before mid-century, “despite the optimists’ evidence of rising real wages.” To whatever degree a product of innocent or willful ignorance, the cumulative effect was that “wherever comparison can be made… staggering differences in life expectancy appear, amounting in the worst decades to an average of twenty years of life expectancy lost by the average male urban wage-earner; and whatever horrors the English statistics showed, the Scottish were invariably even worse.””

Rita Repulsa was once imprisoned in a space dumpster by a sage named Zordon

Contrary to what some internet dwellers want, I will not be talking about a couple of irrelevant old sellouts called Mike and Jay at this time. Do some people really think that I spend my time on thinking about those guys or on watching their dumb videos? I mean, just about everyone on YouTube looks at my channel and at my blog, and I don’t have the time to watch the huge amount of dumb and offensive content that YouTube now offers. On the other hand, if someone were to ask me about Rich Evans, I’d have a different answer. Rich, who’s really the god Bragi in disguise, may spend his time living at a Milwaukee retirement home nowadays, but there is a good reason for this. In order to avoid the terrible battles against Thanos that his brothers Thor and Loki were involved in, Bragi disguised himself as an unassuming, average-looking American citizen and began living on Midgard, after leaving Asgard before it was destroyed in Ragnarok. Since Bragi is renowned for his wisdom, he knew that the other aesir and the Avengers would eventually triumph and defeat Thanos. Bragi didn’t even lift a finger when Thanos was named Sexiest Man Alive by People magazine. But Bragi is no slouch because he still took time to battle against the latest machinations of his long-time nemesis and former sweetheart, the evil space witch Rita Repulsa, in California. As universe-shaking as those events were, I will not be writing about them because they are so well known. I mean, just about everyone on the planet has seen the documentary films Avengers: Infinity War and Avengers: Endgame. Instead, I will be quoting from ‘Paths of Fire: An Anthropologist’s Inquiry into Western Technology’ (1996) by Robert McCormick Adams. I acquired this book at a used books store a few years ago, and, although I’ve read most of it already, I’m not done reading it yet. Still, I have come across plenty of information that I’ve highlighted. I don’t like the book a lot because the author’s writing style isn’t appealing to me, but the book still contains plenty of information that I found to be interesting. The following is a quote from the second chapter. “The next great pulsation even more clearly attests to the context-dependent path of technological change and its many lines of intersection with wider cultural milieus. On present evidence the beginnings of civilization occurred first in Mesopotamia during the middle or latter part of the fourth millennium B.C. That seminal period was very quickly followed by similar developments along the Nile, and not long afterward in the Indus valley. There soon appeared – always with variations around a common core of greater hierarchy and complexity – similar patterns in China and the New World. One may reasonably postulate a greater degree of interconnectedness among these nuclear areas than with the beginnings of agriculture, but once again diffusion does not appear to have been a decisive factor. Particularly the original, Mesopotamian, manifestation has been not unreasonably characterized as an urban revolution, and likened to the Industrial Revolution. Like the latter, the former epoch was comparatively brief, spanning at most a few centuries and possibly much less. Alongside major, concurrent innovations in public institutions were others in the realm of technology. What we know of them is obviously still limited to relatively imperishable categories of material. However, it is noteworthy that they have in common qualities of technical precocity and high artistic creativity. Stone cylinder seals, for example, appearing first at this time, then remained a hallmark of Mesopotamian culture for millennia. This almost iconic class of artifacts was endowed, almost from its first appearance, with a “creative power… such that we meet among its astonishingly varied products anticipations of every school of glyptic art which subsequently flourished in Mesopotamia.” Their distinctive designs, when rolled across lumps of clay, could seal containers or even storerooms against illicit entry, and identify the civic or religious authority responsible for them. Thus they were an integral part of the technology of administration. Fashioned (and initially also partly decorated) with the bow-drill, they were also exemplars of the new technology of the wheel that is first manifested at roughly the same time in wheeled vehicles and wheel-made pottery. Similarly, an examination of jewelry and other metal objects from the so-called Royal Tombs of Ur, a few centuries later, has revealed “knowledge of virtually every type of metallurgical phenomenon except the hardening of steel that was exploited by technologists up to the end of the 19th century A.D. There were comparably far-reaching developments, reflecting most of the technical and stylistic patterns that prevailed for centuries or even millennia afterward, in monumental architecture, the mass production of ceramics, woven woolen textiles, and in all likelihood woodworking. Concurrent and more seminal still was the Mesopotamian invention of writing. While clearly an administrative advance of unmatched power and versatility, there may be some hesitancy in describing it also as a technological achievement. There is nothing to suggest, for example, that early writing was directly instrumental in the refinement or dissemination of other craft techniques, or that any specialists other than scribes and some priests and administrators were themselves literate. Smelted iron had long been known and used in very small quantities, so that the shift away from bronze cannot be attributed to the mere discovery of a new material with valuable inherent properties. At levels of metallurgical skill that had been attained at the beginnings of what is characterized as the Iron Age, iron’s relative hardness was not yet a reliably attainable characteristic. As it became so, new or improved tools – picks, shovels, axes, shears, scythes, chisels, saws, dies, lathes, and levers – cumulatively transformed craft capabilities in fields like transportation and building. But these developments follow, and hence cannot account for, the onset of the Iron Age. Progressive deforestation of much of the ancient Near East, as a consequence of pastoral overgrazing and wood-cutting for copper ore reduction as well as cooking, may have been a more significant factor. Contemporary iron ore reduction processes are not well understood, but were probably several times as fuel-efficient as that of copper. Also helping to explain the shift may have been the wider dispersal of iron ore deposits. The widespread substitution of iron for copper thus may have been economically driven. But it should be kept in mind that the production processes involved were of a pyrotechnological character. This may help to explain why much concurrent experimentation and innovation in other crafts, leading to improvements in glazes, glasses, and frits, and possibly also in metallic plating, had a pyrotechnological basis. The next succeeding punctuation of the technological lull occurred later in the first millennium B.C. Two contributory streams can be distinguished, although by Hellenistic times they had largely coalesced. Originating in the Near East were coinage and alphabetization, both stimulants to administrative advances and the long-distance movement of ideas in conjunction with commerce. As such, they constituted a kind of information infrastructure for the diffusion and utilization of proto-scientific as well as technological understanding. A second contributory stream was centered in the Aegean. Although the Greek world is much more widely heralded as the birthplace of a formal discipline of natural philosophy, it can be credited with some technological contributions as well. If we take into account not merely the number of innovations but the extent to which they found practical application, however, the overall record has to be characterized as a conspicuously limited one: “The Greeks and Romans built a high civilization, full of power and intellect and beauty, but they transmitted to their successors few new inventions. The gear and the screw, the rotary and the water-mill, the direct screw-press, glass-blowing and concrete, hollow bronze-casting, the dioptra for surveying, the torsion catapult, the water-clock and water-organ, automata (mechanical toys) driven by water and wind and steam – this short list is fairly exhaustive, and it adds up to not very much for a great civilization over fifteen hundred years.” Only one of these devices deserves special mention for its economic significance: water wheels for the milling of grain. These too are generally believed to have been very limited in number until a much later time. In all of classical antiquity, there are fewer than a dozen known literary references to any use of water power at all. The dismissal by most classical scholars of the importance of water wheels for grain-milling, relying on the literary evidence, is a conclusion on which Orjan Wikander and others have recently mounted a frontal attack. Criticizing the lack of effort “to establish the fundamental premise of the discussion: the actual technological standard of Roman society,” he holds that the orthodox impression of the extreme rarity of the water mill “has only been produced by the systematic disregard of the evidence for its existence in Antiquity.” Archaeologically attested examples of their use, he is able to show, slowly grew in number over time. The paucity of literary references to water-driven mills, in comparison with medieval ones, can be plausibly questioned on a variety of grounds. But even for the late classical period, the most that Wikander has been able to document for the third, fourth, and fifth centuries A.D. are from eight to eleven occurrences per century across the entire span of the empire. While further findings may well deepen the impact of this criticism, it has not yet displaced the prevailing tendency to identify the Roman agricultural regime with technological stagnation. The existing textual sources that are most informative take the form of compendia of ingenious devices. Evident in the works of authors like Vitruvius (died 25 B.C.) and Hero of Alexandria (who flourished during the late first century A.D.) are great versatility, critical acuity, and engineering competence, but they provide few clues to the context or frequency of use – or even the practicality – of what they describe. Hero of Alexandria’s descriptions of pneumatic and steam-operated toys, for example, are given without reference to the wider potential utilities of the principles involved in their operations. Also of little or no concern to them was the issue of priority of discovery, so that the degree to which technical discoveries or innovations fell into clusters, in space as well as in time, is almost impossible to ascertain. Greek and Hellenistic natural philosophy, for all of the seminal importance with which it is often invested as the source of a unilinear tradition leading to modern science, is of only marginal relevance to the history of technology. This is in no sense to deny its conceptual advances on its Babylonian and Egyptian antecedents. Essentially new was the comprehensive effort to categorize material phenomena and to give rational, lawful explanations for them. “The capricious world of divine intervention was being pushed aside, making room for order and regularity… A distinction between the natural and the supernatural was emerging, and there was wide agreement that causes (if they are to be dealt with philosophically) are to be sought only in the nature of things. But as Finley affirms with a commonplace, “the ancient world was characterized by a clear, almost total, divorce between science and practice. The aim of ancient science, it has been said, was to know, not to do; to understand nature, not to tame her.” As a prototypical applied mathematician, Archimedes of Syracuse (circa 287-212 B.C.) may stand as an exception. Brilliant mechanical innovations like the Archimedean screw for raising water are traditionally associated with his name. But it is suggestive of the isolation in which this was conceived that the principle of the screw apparently found no other applications for more than two centuries – until Hero of Alexandria’s description of the double-screw press and the female screw-cutting machine. A noteworthy feature of Archimedes’s reputed contributions is that so many of them were sophisticated ballistic devices that seem to have been developed only under the extraordinary stimulus of a Roman siege of his native city. Euclid’s (circa 300 B.C.) geometry, in the same vein, ultimately laid the foundations for cadastral surveys. However, he himself eschewed all practical applications. And when Galen (A.D. 129-210) in medicine and physiology and Ptolemy (circa A.D. 150) in cartography are rightly regarded as immensely influential, this largely reflects how they came to be viewed during the Renaissance rather than by their contemporaries.” I will also quote from Robert Stawell Ball’s ‘The Story of the Heavens’ (1886), which is another book that I bought quite a long time ago but still haven’t finished reading yet. “In our exploration of the beautiful series of bodies which form the solar system, we have proceeded step by step outwards from the sun. In the pursuit of this method we have now come to the splendid planet Jupiter, which wends its majestic way in a path immediately outside those orbits of the minor planets which we have just been considering. Great, indeed, is the contrast between these tiny globes and the stupendous globe of Jupiter. Had we adopted a somewhat different method of treatment – had we, for instance, discussed the various bodies of our planetary system in the order of their magnitude – then the minor planets would have been the last to be considered, while the leader of the host would be Jupiter. To this position Jupiter is entitled without an approach to rivalry. The next greatest on the list, the beautiful and interesting Saturn, comes a long distance behind. Another great descent in the scale of magnitude has to be made before we reach Uranus and Neptune, while still another step downwards must be made before we reach that lesser group of planets which includes our earth. So conspicuously does Jupiter tower over the rest, that even if Saturn were to be augmented by all the other globes of our system rolled into one, the united mass would still not equal the great globe of Jupiter. The satellites of Jupiter, the minor planets, and the comets, all tell the weight of the giant orb; and, as they all concur in the result (at least within extremely narrow limits), we cannot hesitate to conclude that the mass of the greatest planet of our system has been determined with accuracy. The results of these measures must now be stated. They show, of course, that Jupiter is vastly inferior to the sun – that, in fact, it would take about 1,047 Jupiters, all rolled into one, to form a globe equal in weight to the sun. They also show us that it would take 316 globes as heavy as our earth to counterbalance the weight of Jupiter. No doubt this proves Jupiter to be a body of magnificent proportions; but the remarkable circumstance is not that Jupiter should be 316 times as heavy as the earth, but that he is not a great deal more.”

Now listening to Article 99 by Danny Elfman and Toni Braxton by Toni Braxton…

On Cambie Street in Vancouver. Summer of 2018.

Cambie Street is a street in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. It is named for Henry John Cambie, chief surveyor of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s western division (as is Cambie Road, a major thoroughfare in nearby Richmond).

There are two distinct sections of the street. North of False Creek, the street runs on a northeast-southwest alignment (following the rotated street grid within Downtown Vancouver). As such, the street direction is approximately 45 degrees to that of the Cambie Bridge, and there is no seamless connection between the two. Instead, Nelson Street carries southbound traffic onto the bridge, and Smithe Street carries northbound traffic away from the bridge. The downtown section of Cambie Street runs from Water Street in Gastown in the north to Pacific Boulevard in Yaletown in the south and is a two-way street for its length.

South of False Creek, the street is a major six-lane arterial road, and runs as a two-way north-south thoroughfare according to the street grid for the rest of Vancouver. This section of the street was originally named Bridge Street, and was first connected to Cambie Street after the first Cambie Bridge opened in 1891; it was renamed Cambie Street after the second Cambie Bridge opened in 1912.

Between King Edward Avenue West and Southwest Marine Drive, the street has a 10 metre wide boulevard with grass and many well established trees on it; the boulevard was designated as a heritage landscape by the city of Vancouver in 1993.

When proposals to build SkyTrain’s Canada Line (formerly known as the Richmond-Airport-Vancouver or RAV Line) along Cambie Street first emerged, they were heavily protested by residents and business owners who wanted to keep the street as a heritage boulevard. They argued in favour of using the existing Arbutus Street rail corridor instead.

Once the decision was made to use the Cambie alignment for the Canada Line anyway, residents along the corridor successfully persuaded authorities to put the rail line in a tunnel instead of running it as a surface route, and to dig the tunnel using a tunnel boring machine. However, due to cost concerns and time constraints, the winning bidder decided to use a cut-and-cover method to build the tunnel – which required disruption to traffic and business along the corridor during the construction. As such, even though it cost less and was much faster than using a tunnel boring machine, the plan drew heavy criticism from area residents and businesses.

During 2006 to 2009, portions of the street south of False Creek were closed to traffic to allow for construction of the line. The cut-and-cover tunnel runs underneath the east side of the street for most of its route. South of West 63rd Avenue, the line emerges from the tunnel and runs on an elevated structure across the Fraser River.

Gregor Robertson, who later became the mayor of Vancouver, was a strong supporter of Cambie Street merchants and spoke regularly about hardships from the Canada Line construction. He called the handling of the rail line construction an “injustice.”

On March 23, 2009, Robertson testified in a lawsuit brought by Cambie Street merchant Susan Heyes, owner of Hazel & Co., in the B.C. Supreme Court regarding damage to her business from the construction, a lawsuit for which she was awarded $600,000 by the B.C. Supreme Court due in part to the fact that there was insufficient action to mitigate the effects of Canada Line construction on Cambie Street merchants. The award for damages was later reversed at the British Columbia Court of Appeal, which determined that while the project had resulted in a legal nuisance to the claimant, the government had acted within its authority and was therefore not liable for damages. Leave for further appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada was subsequently denied. On the Canada Line’s opening day of August 17, 2009, Robertson said Greater Vancouver needed more rapid transit but the Canada Line was a “great start” and that he was a “Johnny-come-lately” to the project.

Now reading The Military Establishment by Adam Yarmolinsky…

Final Fantasy Retrospective – Part IV

Final Fantasy VI for the Super Nintendo.