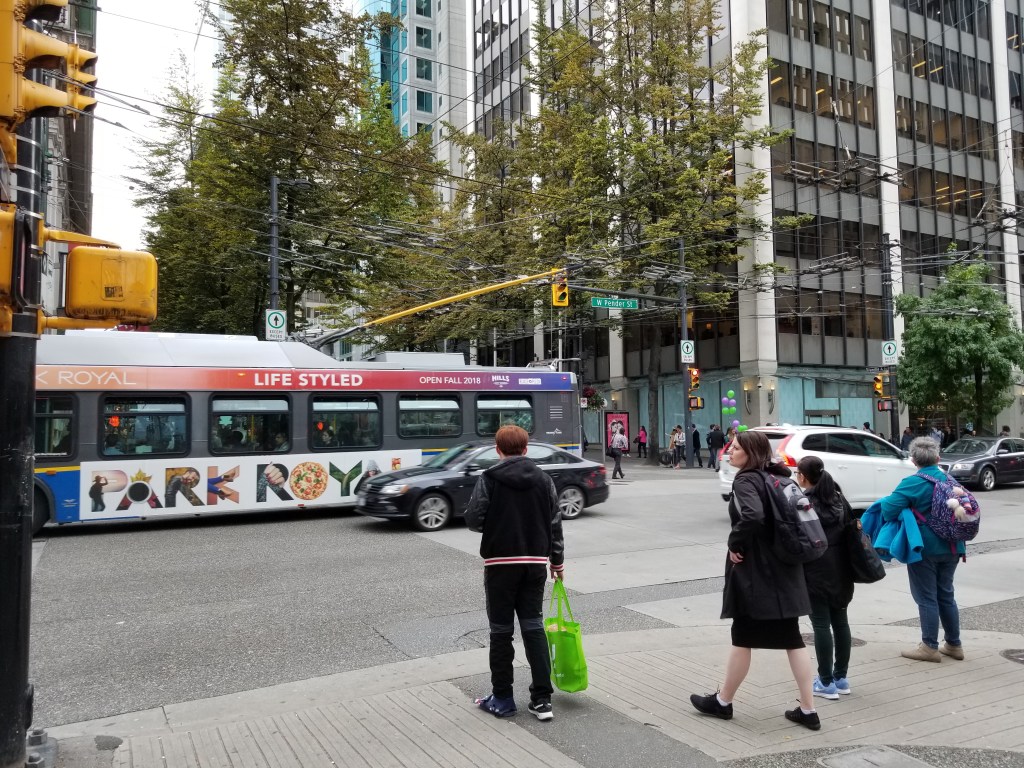

Dunsmuir Street is a major east-west street in downtown Vancouver, British Columbia, running through the heart of the city’s central business district. It stretches from Burrard Street in the west to Cambie Street in the east, where it transitions into Dunsmuir Viaduct, connecting to Prior Street and the Georgia Viaduct. Dunsmuir Street is a key arterial route, parallel to other prominent downtown streets like Georgia Street to the north and Robson Street to the south.

Dunsmuir Street is named after Robert Dunsmuir, a prominent 19th-century Scottish-Canadian coal magnate and politician who played a significant role in British Columbia’s industrial history, particularly through his development of coal mines on Vancouver Island and his involvement in the construction of the Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway.

Dunsmuir Street was established as part of Vancouver’s early grid system in the late 19th century, a period when the city was rapidly growing due to the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) in 1887. The street’s naming reflects the influence of figures like Robert Dunsmuir, whose wealth and political clout shaped much of BC’s early economic landscape.

Over the decades, Dunsmuir Street evolved from a relatively modest thoroughfare into a central artery in Vancouver’s downtown core. By the mid-20th century, it was surrounded by commercial buildings, and by the late 20th century, it became a hub for office towers, cultural institutions, and transit connections, reflecting Vancouver’s growth into a major metropolitan center.

The City of Vancouver has been working on a project to improve Dunsmuir and Melville Streets, focusing on the stretch between Hornby Street and the Coal Harbour Seawall. This initiative, part of the Downtown Bike Network Expansion, aims to make the area safer and more accessible for walking, biking, and rolling (e.g., using wheelchairs or scooters). Public engagement for this project concluded on October 6, 2024, with the city collecting feedback through surveys and in-person events. An engagement summary was expected to be released in late 2024 or early 2025, which should now be available as of May 2025. Construction is slated to begin in 2026, indicating that preparatory work, such as final design approvals, might be underway now. The upgrades will enhance connectivity between key routes, improving access to the Coal Harbour Seawall, a popular recreational area along the waterfront.

Dunsmuir Street is home to several notable buildings, including Bentall Centre (near Burrard Street). It’s a complex of office towers that houses major corporations and is a focal point for business activity. 500 Dunsmuir Street is associated with the Holborn Group of Companies, a real estate firm. The building itself is likely a commercial property, reflecting the street’s role in Vancouver’s business district. Dunsmuir Street is close to cultural landmarks like the Vancouver Art Gallery (on Georgia Street, just north of Dunsmuir) and public spaces like Robson Square, accessible via nearby streets. The Hyatt Regency Hotel is located near Burrard and Dunsmuir, making the area a hub for tourists as well as locals. Retail options, such as those at The Bay store on Granville Street (accessible via Dunsmuir), also contribute to the street’s vibrancy.

Dunsmuir Street is a busy route for vehicular traffic, particularly during rush hours, as it serves as a primary east-west corridor for commuters heading to or from the central business district. The ongoing Dunsmuir/Melville Street upgrades highlight the city’s focus on improving cycling infrastructure. Dunsmuir Street already has a protected bike lane for much of its length, a feature introduced in 2010 as part of Vancouver’s push to become a bike-friendly city. The 2026 upgrades will likely enhance these facilities further. In addition to SkyTrain stations, Dunsmuir Street is served by multiple bus routes, and its proximity to the Granville transit mall (on Granville Street) makes it a key node for public transit users.

The planned upgrades starting in 2026 will likely cause temporary disruptions on Dunsmuir Street, such as lane closures or detours, but the long-term benefits include improved safety and accessibility for all users. Vancouver’s focus on sustainable transit and walkable streets suggests that Dunsmuir Street will continue to evolve into a more eco-friendly corridor, potentially with features like expanded bike lanes, more greenery, and better integration with public transit. As downtown Vancouver grows, Dunsmuir Street may see increased development, such as new high-rises or mixed-use projects, though the city’s emphasis on preserving views and public spaces will likely temper this growth.

Dunsmuir Street’s viaduct section, the Dunsmuir Viaduct, has been a point of contention in Vancouver’s urban planning debates. Some city planners and residents have advocated for its removal (along with the Georgia Viaduct) to reclaim land for parks or housing, a proposal that gained traction in the 2010s and 2020s. As of May 2025, no final decision has been widely publicized, but this could be a future change to watch for.

Dunsmuir Street is a vital part of Vancouver’s downtown core, blending historical significance with modern urban functionality. It’s a hub for business, transit, and cultural activity, and the ongoing upgrades (set to begin in 2026) will enhance its role as a pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly corridor. Its proximity to landmarks like the Bentall Centre, SkyTrain stations, and the Coal Harbour Seawall makes it a central artery in the city’s daily life.

Georgia Street is an east–west street in the cities of Vancouver and Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada. Its section in Downtown Vancouver, designated West Georgia Street, serves as one of the primary streets for the financial and central business districts, and is the major transportation corridor connecting downtown Vancouver with the North Shore (and eventually Whistler) by way of the Lions Gate Bridge. The remainder of the street, known as East Georgia Street between Main Street and Boundary Road and simply Georgia Street within Burnaby, is more residential in character, and is discontinuous at several points.

West of Seymour Street, the thoroughfare is part of Highway 99. The entire section west of Main Street was previously designated part of Highway 1A, and markers for the ‘1A’ designation can still be seen at certain points.

Starting from its western terminus at Chilco Street by the edge of Stanley Park, Georgia Street runs southeast, separating the West End from the Coal Harbour neighbourhood. It then runs through the Financial District; landmarks and major skyscrapers along the way include Living Shangri-La (the city’s tallest building), Trump International Hotel and Tower, Royal Centre, 666 Burrard tower, Hotel Vancouver and upscale shops, the HSBC Canada Building, the Vancouver Art Gallery, Georgia Hotel, Four Seasons Hotel, Pacific Centre, the Granville Entertainment District, Scotia Tower, and the Canada Post headquarters. The eastern portion of West Georgia features the Theatre District (including Queen Elizabeth Theatre and the Centre in Vancouver for the Performing Arts), Library Square (the central branch of the Vancouver Public Library), Rogers Arena, and BC Place. West Georgia’s centre lane between Pender Street and Stanley Park is used as a counterflow lane.

East of Cambie Street, Georgia Street becomes a one-way street for eastbound traffic, and connects to the Georgia Viaduct for eastbound travellers only; westbound traffic is handled by Dunsmuir Street and the Dunsmuir Viaduct, located one block to the north.

East Georgia Street begins at the intersection with Main Street in Vancouver’s Chinatown, then runs eastwards through Strathcona, Grandview–Woodland and Hastings–Sunrise to Boundary Road. East of the municipal boundary, Georgia Street continues eastwards through Burnaby until its terminus at Grove Avenue in the Lochdale neighbourhood. This portion of Georgia Street is interrupted at several locations, such as Templeton Secondary School, Highway 1 and Kensington Park.

Georgia Street was named in 1886 after the Strait of Georgia, and ran between Chilco and Beatty Streets. After the first Georgia Viaduct opened in 1915, the street’s eastern end was connected to Harris Street, and Harris Street was subsequently renamed East Georgia Street.

The second Georgia Viaduct, opened in 1972, connects to Prior Street at its eastern end instead. As a result, East Georgia Street has been disconnected from West Georgia ever since.

On June 15, 2011 Georgia Street became the focal point of the 2011 Vancouver Stanley Cup riot.

The Lost Decade is commonly used to describe a period in Japan beginning in the 1990s, during which economic stagnation became one of the longest-running economic crises in recorded history. Later decades are also included in some definitions, with the period from 1991 through 2011 (or even through 2021) sometimes being referred to as Japan’s Lost Decades.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the Lost Decade

The Lost Decade is a term initially coined to refer to the decade-long economic crisis in Japan during the 1990s. Japan’s economy rose meteorically in the decades following World War II, peaking in the 1980s with the largest per capita gross national product (GNP) in the world. Japan’s export-led growth during this period attracted capital and helped drive a trade surplus with the U.S.

To help offset global trade imbalances, Japan joined other major world economies in the Plaza Agreement in 1985. In accord with this agreement, Japan embarked on a period of loose monetary policy in the late 1980s. This loose monetary policy led to increased speculation and a soaring stock market and real estate valuations.

In the early 1990s, as it became apparent that the bubble was about to burst, the Japanese Financial Ministry raised interest rates, and ultimately the stock market crashed and a debt crisis began, halting economic growth and leading to what is now known as the Lost Decade. During the 1990s, Japan’s gross domestic product (GDP) averaged 1.3%, significantly lower as compared to other G-7 countries. Household savings increased. But that increase did not translate into demand, resulting in deflation for the economy.

The Lost Decades

In the following decade, Japan’s GDP growth averaged only 0.5% per year as sustained slow growth carried over right up until the global financial crisis and Great Recession. As a result, many refer to the period between 1991 and 2010 as the Lost Score, or the Lost 20 Years.

From 2011 to 2019, Japan’s GDP grew an average of just under 1.0% per year, and 2020 marked the onset of a new global recession as governments locked down economic activity in reaction to the Covid-19 pandemic. Together the years from 1990 to the present are sometimes referred to as Japan’s Lost Decades.

The pain is expected to continue for Japan. According to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, recent growth rates imply that Japan’s GDP will double in 80 years when previously it doubled every 14 years.

What Caused The Lost Decade?

While there is some agreement on the events that led up to and precipitated the Lost Decade, the causes for Japan’s sustained economic woes are still being debated. Once the bubble burst and the recession took place, why did persist through successive years and decades? Demographic factors, such as Japan’s aging population, and the geopolitical rise of China and other East Asian competitors may be underlying, non-economic factors. Researchers have produced papers delineating possible reasons why the Japanese economy sank into prolonged stagnation.

Keynesian economists have offered several demand-side explanations. Paul Krugman opined that Japan was caught in a liquidity trap: Consumers were holding onto their savings because they feared that the economy was about to get worse. Other research on the subject analyzed the role played by decreasing household wealth in causing the economic crisis. “Japan’s Lost Decade,” a 2017 book, blames a “vertical investment-saving” curve for Japan’s problems.

Monetarist economists have instead pointed to Japan’s monetary policy before and during the Lost Decade as too restrictive and not accommodative enough to restart growth. Milton Friedman wrote, in reference to Japan, that “the surest road to a healthy economic recovery is to increase the rate of monetary growth to shift from tight money to easier money, to a rate of monetary growth closer to that which prevailed in the golden 1980s but without again overdoing it. That would make much-needed financial and economic reforms far easier to achieve.”

Despite these various attempts, Keynesian and Monetarist views on Japan’s extended economic malaise generally fall short. Japan’s government has engaged in repeated rounds of massive fiscal deficit spending (the Keynesian’s solution to economic depression) and expansionary monetary policy (the Monetarist prescription) without notable success. This suggests that either the Keynesian and Monetarist explanations or solutions (or both) are likely mistaken.

Austrian economists have, on the contrary, argued that a period of extended economic stagnation is not inconsistent with Japan’s economic policies that throughout the period acted to prop up existing firms and financial institutions rather than letting them fail and allowing entrepreneurs to reorganize them into new firms and industries. They point to the repeated economic and financial bailouts as a cause of—rather than a solution to—Japan’s Lost Decades.

What Is Japan’s GDP Growth Rate?

As of the first quarter of 2024, Japan’s annual GDP growth rate stood at a negative 0.2 percent compared to the same period one year prior. This indicates that the country’s GDP contracted slightly rather than growing.

How Big Is Japan’s Economy?

As of 2024, Japan boasts the world fourth-largest economy, behind the United States, China, and Germany.The country’s economy is characterized by a strong manufacturing sector and exports.

What Is Japan’s Lost Generation?

The “Lost Generation” is a concept closely related to Japan’s Lost Decades. The term refers to those Japanese university graduates who entered the economy during the employment freezes characteristic of the Lost Decades. This primarily includes people who graduated in the 1990s and 2000s. As a consequence of these circumstances, members of the Lost Generation may have had to take on low-wage temporary work over stable employment with robust retirement benefits—teeing up a potential pension crisis for the nation.

The Bottom Line

The Lost Decade, also known as the Lost Decades, refers to an extended stretch of economic stagnation in Japan beginning in the early 1990s. This era of poor economic performance has been characterized by low GDP growth, recessions, and deflation. Economists have posited multiple hypotheses to attempt to understand and explain the root causes and potential solutions of Japan’s economic downturn.

James Stavridis, the former NATO supreme allied commander for Europe, said Sunday that Russia has displayed “amazing incompetence” noting the several Russian generals that have died since the beginning of the invasion of Ukraine.

“In modern history, there is no situation comparable in terms of the deaths of generals,” Stavridis said during a radio interview on WABC 770 AM. “Just to make a point of comparison here, the United States in all of our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq…in all of those years and all of those battles, not a single general lost in actual combat.”

The former commander added that “on the Russian side, in a two-month period, we have seen at least a dozen, if not more Russian generals killed. So amazing incompetence.” He also criticized other aspects of the Russian military’s performance, by saying that they have an “inability to conduct logistics” and “bad battle plans.”

He also noted the loss of the Moskva, a Russian warship that the Pentagon said Ukrainians sunk with a missile last month. The loss of the ship was a $750 million hit to the Russian military, according to an analysis by Forbes Ukraine.

“It’s been a bad performance by the Russians thus far,” Stavridis said.

In late April, Newsweek compiled a list of several Russian generals who had been killed during the war. These include Major General Andrey Sukhovetsky, who served as the commanding general of Russia’s 7th Guards Airborne Division and deputy commander of the 41st Combined Arms Army, and was reportedly killed by sniper fire in February. Vladimir Frolov, deputy commander of Russia’s 8th Guards Combined Arms Army, was also reportedly killed last month.

A European diplomat, who spoke with Foreign Policy on the condition of anonymity about the deaths of Russian generals in March, said the failure of communications equipment has made them vulnerable.

“They’re struggling on the front line to get their orders through,” the diplomat said. “They’re having to go to the front line to make things happen, which is putting them at much greater risk than you would normally see.”

In an interview with ABC News last week, former U.S. ambassador to NATO Douglas Lute said he believes Russian forces can’t seize the Ukrainian capital city of Kyiv or replace Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s government.

“Putin is trying to assess what might be possible and looking for opportunities and he’ll grab the first good one available. Right now, there don’t seem to be many good opportunities for Vladimir Putin,” he said.

The Czech president has signed an amendment essentially equating communism with Nazism.