Looking at why Bloober Team doesn’t understand the original Silent Hill 2’s aesthetic, cinematic atmosphere or gameplay.

Either because of sheer incompetence or through trying to undermine the artistic merit of the original, SH2R feels like a streamer miniseries. Thanks for watching.

Timestamps:

0:00 Introduction

01:04 OG Silent Hill 2 and Remakes Overall Feel

04:34 Silent Hill 2 Remake Full Analysis and Comparisons

10:04 Closing Thoughts

Viticulture was introduced to this fertile region of Aquitaine by the Romans, and intensified in the Middle Ages. The Saint-Emilion area benefited from its location on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela and many churches, monasteries and hospices were built there from the 11th century onwards. It was granted the special status of a ‘jurisdiction’ during the period of English rule in the 12th century. It is an exceptional landscape devoted entirely to wine-growing, with many fine historic monuments in its towns and villages.

Brief synthesis

The territory of the Jurisdiction of Saint Emilion is located in the Nouvelle Aquitaine region, in the department of the Gironde. It covers 7,847 hectares. Delimited to the south by the Dordogne and to the north by the Barbanne stream, it is composed of a plateau (partly wooded), hillsides, concave valleys and a plain. Eight communes comprise the Jurisdiction, which was established in the 12th century by the King of England, John Lackland, Duke of Aquitane.

The landscape of the Jurisdiction of Saint Emilion is a monoculture, comprised exclusively of vines that were introduced intact and have remained active until today. Viticulture was introduced into this fertile region of Aquitaine by the Romans and intensified in the Middle Ages. The Saint Emilion territory benefited from its location of the Pilgrimage Route to Santiago de Compostela, and several churches, monasteries and hospices were built as of the 11th century.

This long wine growing history marked in a characteristic manner the monuments, architecture and landscape of the Jurisdiction. This alliance of the built and the natural, of stone, vine, wood and water, has created an eminent cultural landscape.

Before viticulture secured its place in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, castles were built on dominant sites to serve seigniorial residencies. However, the “chateaux” of the vineyards were located in the centre of their domains. They date from the mid-18th century to the early 19th century.

The villages are characterized by modest stone houses dating from the early 19th century. Intended for the vineyard workers, they were never more than two storeys high and were grouped in small hamlets. The chais (wine storehouses) are large rectangular functional structures built in stone or a mixture of brick and stone, with tiled double-pitched roofs.

At Saint Emilion the most important religious monuments are the Hermitage or Grotto of Saint Emilion, the Monolithic Church with its bell tower, the medieval monastic catacombs and the Collegiate Church with its cloister. This ensemble, mostly Romanesque in origin, clusters around the pilgrimage centre of the hermit saint. There is also a group of secular monuments, including the massive keep of the Château du Roi and the ruins of the Palais Cardinal. Romanesque churches are present in each of the other seven villages. The enormous Pierrefitte menhir is in the commune of Saint-Sulpice-de-Faleyrens.

Criterion (iii):The Jurisdiction of Saint Emilion is an outstanding example of an historic vineyard landscape that has survived intact and in activity to the present day.

Criterion (iv): The historic Jurisdiction of Saint Emilion illustrates in an exceptional way the intensive cultivation of grapes for wine production in a precisely defined area.

Integrity

The integrity of the landscape and the harmony offered by the ensemble of the site are due to the permanence of the vine culture, and the productive organization of the territory. The constructions or village ensembles do not correspond to a single architectural design, but are, as testifies the historic heart of Saint Emilion, the result of a long evolution over several centuries, from the 7th century and throughout the 19th and 21st centuries.

The communities have enjoyed the best part of the characteristics of the territory and develop their activities and life style, without destroying it. The culture of the land, the exploitation of the quarries, the urban establishments and development, and the construction of religious edifices and houses have all created a landscape in perfect harmony with the topography and resources of the place.

Authenticity

Although the Jurisdiction is today confronted with a decreasing population and the weakening of sub-soil due to the quarries, it remains a dynamic living territory, integrally conserving its wine growing tradition, looking to the future.

Protection and management requirements

In 1986, a safeguarded sector was created under the “Malraux” Law of 1962.

Apart from individual protection measures for buildings in application of the Heritage Code, (Historic Monuments), protection measures and town planning and enhancement documents ensuring the development of the territory have been established to preserve the site and to manage it in the continuity with its inscription on the World Heritage List: a voluntary heritage charter in 2001, a territorial project in 2004, a local urbanism plan for each of the eight communes in 2007, six of which are within the boundaries of the property and two in the buffer zone, as well as a protection zone for intercommunal architectural, urban and landscape heritage in 2007.

The Safeguarding and Enhancement Plan (PSMV) of the remarkable heritage site of the town of Saint Emilion was approved in 2010. A flood risk mitigation plan (PPRI) and a Plan for the Risk of Land Movement (PPRMT) for the concerned communities has also been prepared. A Management Plan for the property was also prepared in 2013. In particular, it deals with diminishing populations due to housing problems and the lack of available land resources and specifies development conditions for the property to render it compatible with the preservation of its Outstanding Universal Value. In cooperation with the services of the State, solutions are advocated to enable a better landscape integration of the recently constructed chais.

Seven Natural Zones of Ecological, Floral and Faunal Interest (ZNIEFF) concern the territory. These are sectors particularly characterised by their biological interest. The ZNIEFF of the communes of Saint Christophe des Bardes and Saint-Laurent des Combes protect the faunal and floral interest of the wooded “Mediterranean Belt” of the Jurisdiction. The Dordogne is concerned both by a ZNIEFF and by a Natura 2000 zone.

In this post, I will continue to quote from ‘Paths of Fire: An Anthropologist’s Inquiry into Western Technology’ (1996) by Robert McCormick Adams. But, before I do that, I will mention some supplements that I discovered and tested recently. I already made a post in which I specified that omega-3 supplements are helpful for people that have ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). The benefits of consuming omega-3 fatty acids for people with ADHD have been known for decades. Therefore, this information isn’t really new or rare. I also made a post in which I mentioned that ashwagandha (withania somnifera) supplements can be beneficial for some people. Of course, I did this quite a long time ago. Since then, I’ve discovered supplements that are just as good or even better for me because I’ve been putting my unique AI (autistic intelligence) to work on the problem of improving my diet so that I can feel better, and feeling better is very important for me because everyday life is very difficult and problematic for people like me (people that have AuDHD) in this neurotypical society that we live in. I won’t get into all of the information that I’ve acquired so far because this would take up an entire post. But I will mention the most important supplements that I have. I still consider omega-3 supplements to be some of the best supplements in existence, but there is a more effective dopamine amplifier for people with ADHD out there. It’s called L-Tyrosine. There are dozens of dopamine amplifiers that one can purchase, but the amino acid L-Tyrosine is the most effective one that I’ve discovered so far. When it comes to something that can diminish the problems of autism during the day, my best discovery so far is the flavonoid Luteolin. Like many other supplements, Luteolin has more than one benefit. It may help manage chronic inflammation-related conditions such as pain, allergies, respiratory issues, and neuroinflammation. It scavanges free radicals and reactive oxygen species, protecting cells from oxidative stress. This contributes to potential benefits in cardiovascular health, liver protection, and aging-related damage. Luteolin crosses the blood-brain barrier, reducing brain inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative damage. It may protect against ischemia/reperfusion injury, atherosclerosis, and heart failure by improving contractility, reducing fibrosis, and blocking oxidative stress. It has anti-cancer potential because it inhibits tumor proliferation, induces apoptosis, and modulates pathways like PI3K/Akt and STAT3 in various cancers. It has anti-allergic effects (e.g., reducing histamine-related inflammation), wound healing effects, and antimicrobial/antiviral activity. Overall, Luteolin is the best supplement that I currently have. It helps me to feel calm, energetic, less depressed, and more willing to talk to neurotypicals and to deal with their shenanigans. Before I began consuming Luteolin a little while ago, I felt absolutely awful every day. Feeling awful every day is typical for people like me. But now I actually kind of look forward to the next day instead of dreading it. Another supplement that is essential for me when it comes to feeling better during the day is Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA). PEA helps with chronic and neuropathic pain relief, neuroprotection and brain health, and anti-inflammatory and immune modulation. It also contributes to improvements in irritable bowel syndrome, endometriosis-related pelvic pain, migraines, sleep disturbances linked to pain/stress, and even autism spectrum disorder symptoms. The last essential supplement for me is called Glycine. This amino acid is helpful when it comes to improved sleep quality. People with ADHD have a number of problems when it comes to sleeping normally (neurotypically). Glycine, when consumed before bed, reduces time to fall asleep, enhances deep sleep, and decreases daytime fatigue and sleepiness. It also provides anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, metabolic health support, mental health and neurological benefits, cardiovascular protection, and collagen and skin/joint health. Moreover, there’s some evidence that it reduces nighttime urinary frequency, that it protects the liver, and that it has longevity benefits. The other supplements that I’ve tried are mainly antioxidants such as Quercetin and Sulforaphane. I won’t get into the many benefits of consuming antioxidants in this post because they’re not as essential for my everyday well-being as the supplements that I’ve mentioned. Therefore, I will leave the information about antioxidants and the details of my everyday consumption routine for a future post. I spent several hundred dollars in the last few months on buying supplements that I didn’t know about before and testing them. This activity, in which I have been engaging on and off for more than a year, turned out to be well worth it. Since there’s no help or medicine for people with autism, as there are for people with other health conditions, supplements at least make life less unbearable. Anyway, the following are quotes from the sixth chapter, titled ‘The United States Succeeds to Industrial Leadership’. “Hog production is perhaps the most notable example, with the number of hogs slaughtered in Chicago alone increasing from 270,000 per year at the beginning of the war to a level of 900,000 at the end. Federal civil spending in the decade after the war (now including veterans benefits and interests payments on the debt) was approximately twice as high in real terms as it had been in the 1851-1860 decade. Increase of this magnitude carry a significance of their own. We should not lose sight of the transformative effects of the sheer scale of the Union war effort. During the period of the war itself, federal expenditures rose ten to fifteenfold in real terms. The army’s Quartermaster Department, growing from a skeleton force at the outset and independent of expenditures by other departments on ordnance and troop relations, was by the end of the war “consuming at least one-half the output of all northern industry” and spending at an annual level of nearly a half-billion dollars. While the initial weakening in the ranks of states’ rights advocates must be associated with the secession and the congressional acts and constitutional amendments that followed, the irreversibility of the trend away from those views must also owe something to increasing familiarity with, and consequently acceptance of, this previously undreamt-of scale of federal expenditures. Achieving such increases was more than a matter of simply ratcheting up the scale of existing practices. Intimately associated with them were technological advances associated with railroads and the telegraph, for example. These were absolutely indispensable in facilitating military planning, maintaining command-and-control, and executing logistical movements, throughout an enormous theater of war that was being conducted at new levels of complexity. The experience thus gained would be readily translatable into the increasingly national scale of corporate activities at war’s end. The supplying of army ordnance was technologically conservative but in other respects well managed. Difficulties with fusing impeded what might otherwise have been significant changes in the design and effectiveness of artillery, and repeating rifles, already known earlier and also of great potential importance, were introduced into service only belatedly and on a very limited scale. Relatively new technologies – steam power, screw propellors, armor plating and iron ships – impacted much more heavily on naval warfare. In Dupree’s judgment, the Navy’s record in supporting these new technologies with research and qualified management was an excellent one: “in no important way did they further the naval revolution, but to keep pace with it was a major accomplishment.” Again, it may well be that the power of a successful example of quick and resourceful innovation at a hitherto unanticipated scale was the key lesson that was later passed on to peacetime industrial enterprises. Across a wide range of industries, developments comparable to those in steel and fossil fuels were occurring in approximately the same period of time. Growing, mass markets, partly as a result of steeply reduced transportation costs, were for the first time making substantial economies of scale an attainable goal. They required in particular, however, massive investments and readiness to accept long time horizons. In addition, they called for entrepreneurial vision to be extended in a number of new directions: toward backward and forward integration, as we have noted; toward improved selection and training of managerial personnel; toward stability of full-production levels as a key cost-saving measure; toward greater and more continuous emphasis on product improvement; toward improved labor relations; and, not least, toward unprecedented attention to marketing considerations. Price reduction, on the other hand, for the most part was not a dominant goal. Instead, the industrial giants “competed for market share and profits through functional and strategic effectiveness. They did so functionally by improving their product, their processes of production, their marketing, their purchasing, and their labor relations, and strategically by moving into growing markets and out of declining ones more quickly and effectively, than did their competitors. The enormous size of the internal American market clearly presented special challenges and opportunities. This is nowhere more evident than in the chemical industry. Still of very minor proportions at the end of the Civil War, it was largely limited to explosives and fertilizer manufacture. Growing rapidly to meet the demand, it was comparable in size to German industry, the dominant force in international trade, already by the time of World War I. In recognition of the size and rapid growth of the U.S. market, especially in petroleum products, U.S. companies naturally focused on the special problems of introducing large-volume, continuous production and finding ways to take advantage of the potential economies of scale they offered. As L. H. Baekeland, the discoverer of bakelite, said of the transition he had to make from laboratory flasks to industrial-scale production of this synthetic resin not long after the turn of the century, “an entirely new industry had to be created for this purpose – the industry of chemical machinery and chemical equipment.” With heavy capital investment for new plant in prospect, fairly elementary laboratory problems of mixing, heating, and contaminant control became much more difficult to handle with precision and assurance of quality. This largely explains the distinctive existence in the United States of chemical engineering as a university-based discipline. Still, it needs to be recognized that profitability, not absolute market dominance, remained the major consideration. Chandler quotes a revealing letter advocating the policies that the E. I. du Pont de Nemours Powder Company would presently follow. It urged that the company not buy out all competition but only 60 percent or so, since by making unit costs for 60 percent cheaper they would be assured of stable sales in times of economic downturn at the expense of others: “In other words, you could count upon always running full if you make cheaply and control only 60%, whereas, if you own it all, when slack times came you could only run a curtailed product.” Thus “in the United States the structure of the new industries had become, with rare exceptions, oligopolistic, not monopolistic. This was partly because of the size of the marketplace and partly because of the antitrust legislation that reflected the commitment of Americans to competition as well as their suspicion of concentrated power. American railroads deserve to be considered as a final, and in many ways most significant, example of industrial and corporate growth. Alfred Chandler had demonstrated that “the great railway systems were by the 1890s the largest business enterprises not only in the United States but also in the world.” Thus they were unique in the size of their capital requirements, and hence in the role that financiers played in their management. Ultimately even more important, because they were widely emulated, were organizational advances in which the railroads “were the first because they had to be,” developing “a large internal organizational structure with carefully defined lines of responsibility, authority, and communication between the central office, departmental headquarters, and field units.” Railroad managers became the first such grouping to define themselves, and to be generally recognized, as career members of a new profession. Railroads had quickly become the central, all-weather component of a national transportation and communication infrastructure. Around them, depending on their right-of-way and facilities, grew up further, closely allied elements of that infrastructure: telegraph and telephone lines and the corporate giants controlling them; a national postal system; and, with frequently monumental urban railroad stations as key transfer points, the new and rapidly growing urban traction systems. Added to this mix by the end of the century was railroad ownership of the major domestic steamship lines. The total length of the networks of track that were placed in railroad service over successive periods of time can serve as a convenient index of aggregate railroad growth. Extensions of track naturally accompanied growth in areas calling for railroad services as incoming population claimed new lands for settlement. But no less importantly, the increasing density of the networks reflected the essential role that railroads had begun to fill in the movement and marketing of growing agricultural surpluses, internationally as well as in the cities of the eastern seaboard. The major epoch of railroad expansion came to an end at about the time of World War I. Albert Fishlow has shown that productivity improved on American railroads at a faster rate during the latter half of the nineteenth century than in any other industrial sector. He adduces many factors that were involved: economies of scale and specialization as trackage lengthened and firs consolidated; industrywide standardization; technological improvements (heavier rails and locomotives and larger rolling stock); and the growing experience of the railroad work force and management. By 1910 real freight rates had fallen more than 80 percent and passenger charges 50 percent from their 1849 levels. The multiplicity of factors accounting for the marked growth in railroad productivity parallels that in the steel and petroleum industries and is, in fact, a general characteristic of the period. As Robert Fogel has succeeded in demonstrating for American railroads (vis a vis canals in particular), “no single innovation was vital for economic growth during the nineteenth century.” For the American economy more generally, he has reached the conclusion that “there was a multiplicity of solutions along a wide front of production problems.” This implies that growth was a relatively balanced process, not dependent on breakthroughs brought about by “overwhelming, singular innovations” narrowly affecting only one or a few “leading sectors.” How universally this applies is a separate question. I have concluded earlier that there was indeed a handful of key innovations and leading sectors of growth at the heart of the Industrial Revolution in England, and will presently argue that our current phase of growth is heavily dependent on a few technological innovations like semiconductors and the computer industry they led to.”

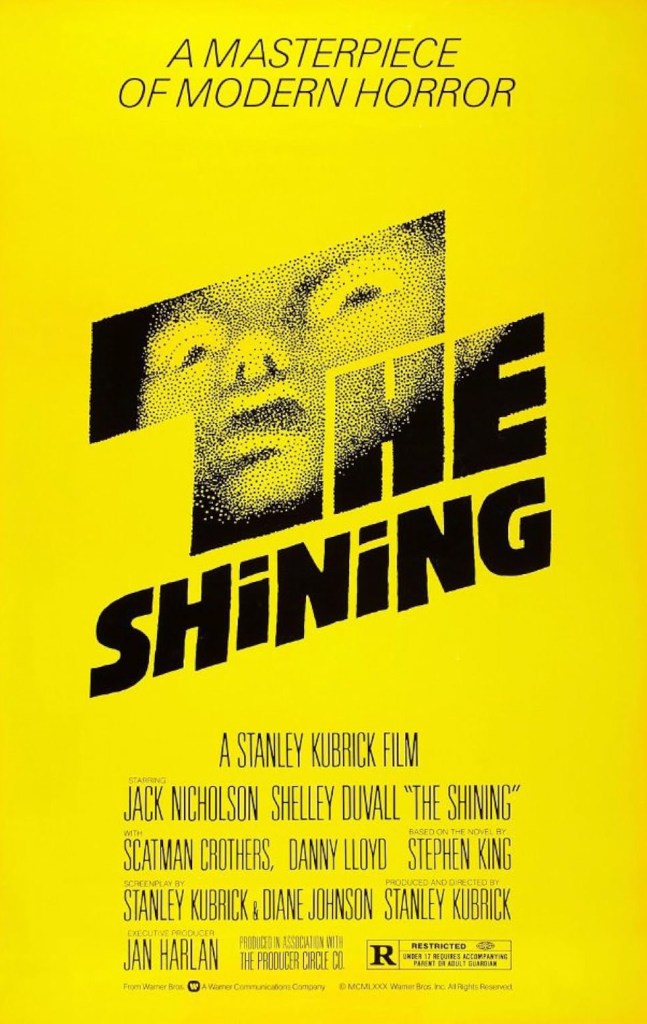

sup nerds. Stanley Kubrick’s final film, Eyes Wide Shut, recently got a 4K Criterion release. This restoration proved to be quite divisive online, sparking a debate as to which version was superior. Is the new colour grading and added film grain an improvement, or does it take away from the dreamy feel of the original Blu-ray? Let’s compare the two to see why they look so different.

Hope you all enjoy 🙂

Pacific Boulevard runs along the northern edge of False Creek, a central waterway in Vancouver, and serves as a defining boundary for Yaletown. The neighborhood itself is roughly bounded by Nelson, Homer, Drake, and Pacific streets, as noted in the history provided by the Roundhouse Community Centre. Pacific Boulevard is a bustling corridor that connects Yaletown to other parts of downtown Vancouver, sitting between the Granville Street and Cambie Street bridges. It’s a major thoroughfare that offers both practical access and a scenic backdrop with views of False Creek.

Yaletown, including the area around Pacific Boulevard, has a rich history tied to Vancouver’s development. According to the Roundhouse Community Centre, the area was initially shaped by the arrival of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1887. By 1900, the city planned a new eight-block warehouse district in what is now recognized as modern Yaletown, with Pacific Boulevard marking its southern edge. Back then, this area was a hub for processing, repackaging, and warehousing goods, thanks to its proximity to the railway and waterfront. It remained largely industrial until the late 20th century.

The transformation of Yaletown—and Pacific Boulevard by extension—began in the late 1970s and 1980s when young urban professionals started moving in, drawn by the affordable and attractive old warehouses. The area’s revitalization kicked into high gear after Expo 86, the world’s fair held in Vancouver, which turned Yaletown into a festival site and sparked widespread redevelopment. Today, Pacific Boulevard is part of a neighborhood known for its mix of art galleries, retail stores, restaurants, and residential towers, as described in the same historical overview.

Pacific Boulevard is home to several notable spots. David Lam Park, 1300 Pacific Boulevard, is a 12-acre park located right on Pacific Boulevard. It’s a large open space adjacent to Yaletown. It’s a popular spot for events, especially in spring and summer, and offers a place to relax with views of False Creek. The park hosts events like the annual lantern procession and “Labyrinth of Light” around December 21st, organized by the Roundhouse Community Centre. Roundhouse Community Centre is located near Pacific Boulevard. This centre is a hub for community activities and events, reflecting the area’s evolution from industrial to cultural. It’s tied to the history of Yaletown and often organizes events that spill into nearby spaces like David Lam Park. The street is dotted with businesses catering to both locals and visitors. For example, Atlantis Dental Yaletown at 1278 Pacific Boulevard offers dental services with extended hours (8:00 AM to 8:00 PM, Monday to Wednesday). Similarly, P Nails & Spa at 1271 Pacific Boulevard, formerly Posy Fingers & Toes Spa, provides nail and spa services, reflecting the area’s focus on lifestyle and wellness.

Today, Pacific Boulevard in Yaletown is a lively, pedestrian-friendly area that reflects the neighborhood’s “trendy” reputation. It’s a mix of modern high-rises, converted warehouses, and green spaces, with a strong emphasis on urban living. The street itself is a blend of functionality—connecting key parts of downtown—and leisure, with proximity to parks, dining, and cultural spots. It’s a hotspot for both residents and tourists, especially given its location near False Creek, which offers scenic views and access to seawall pathways for walking or cycling.

Pacific Boulevard is easily accessible via public transit, with the Yaletown-Roundhouse SkyTrain station nearby on the Canada Line. It’s also a short walk from downtown Vancouver. The area is active throughout the day, with businesses like Atlantis Dental operating from 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM, and the park and seawall drawing crowds for recreation at all hours. As noted, David Lam Park hosts seasonal events, making Pacific Boulevard a focal point for community gatherings, especially in warmer months or during festivals like the winter solstice lantern procession. Pacific Boulevard in Yaletown is a dynamic street that encapsulates the neighborhood’s evolution from an industrial warehouse district to a trendy urban hub. It’s a place where history, modernity, and community intersect, offering a mix of green spaces, cultural activities, and lifestyle amenities.