Dead Space is one of the best survival horror games of all time. It’s got some incredible lore with some excellent storytelling. Both Dead Space 1 & 2 are masterclasses in their own ways. Dead Space 3 starts to fall off right away but manages to finish strong toward the end.

________________________________________

Timestamps:

0:00 Intro

0:46 Dead Space 1

23:56 Dead Space 2

56:57 Dead Space 3

1:31:11 Outro

Autistic people have significantly lower life expectancies than the rest of the population. In 2022, the average global life expectancy is approximately 72 years old. For autistic people, though, the average life expectancy ranges from 39.5 years to 58 years.

Some of the psychological stressors that autistic people experience are a result of existing in a world that has not been designed to meet their needs. Society is set up with various behavior expectations that are challenging, uncomfortable, or even impossible for some autistic people, such as eye contact, sitting still in appointments and meetings, and using nonverbal communication in conversations. Navigating systems designed for neurotypical people is stressful for neurodivergent people, particularly autistics, and this chronic stress contributes to differences in life expectancy.

This article further explores the connection between autism and lower life expectancy.

One major contributor to life expectancy differences for autistic versus non-autistic people is comorbid genetic and medical conditions. Compared to non-autistic people, autistics are at higher risk for several genetic disorders that are linked to shorter life expectancy, including Down syndrome, muscular dystrophy, and Fragile X syndrome.

Autistic people are additionally more likely to experience neurological disorders such as epilepsy and hydrocephalus, sleep disorders, and gastrointestinal disorders.

Autistic people are also at higher risk for mental health issues compared to those who are not autistic. This includes anxiety, depression, psychotic disorders, and trauma disorders. This added risk for mental health diagnoses means that autistic people are at higher risk than non-autistic people of suicide.

This manifests not only in societal expectations but in “treatments” that are often recommended for autistic people. For example, many autistic people who received applied behavioral analysis (ABA) treatment report that the emphasis on compliance and eliminating autistic behaviors is traumatic and abusive.

Autistic people present in a wide variety of ways, and no two autistic people are alike. Sometimes, autistic people are identified in terms of their “functioning.” Functioning labels are not specific diagnoses but are intended to determine how much support an individual needs in their daily life and survival.

Some researchers and providers attempt to differentiate levels of autism, identifying how expansive an individual’s support needs are. This system is limited, as individuals might have strengths and weaknesses in different areas rather than easily fitting into one category. Additionally, illness, stress, or burnout can cause someone’s level or presentation to change day to day or even hour to hour.

At the same time, some autistic people might require high support throughout their lifetime. Research has shown that those with higher support needs have shorter life expectancies than those with fewer support needs. Those who are able to manage independently live, on average, almost 20 years longer than those who require substantial support.

In addition, those who require ongoing support are at risk for abuse and maltreatment by caregivers. This increased risk for abuse likely contributes to lower life expectancy for autistic people with high support needs.

For children, autism can be diagnosed by a psychologist, psychiatrist, or developmental specialist. For adults, autism can be diagnosed by psychologists or psychiatrists with appropriate training. Autism is diagnosed through a psychological evaluation, which has multiple components and may include:

– Diagnostic or Intake Interview: An appointment with the evaluator during which they ask extensive questions about history, symptoms, et cetera.

– Collateral Interviews: Some evaluations include interviews with a parent or caregiver in an effort to gather more early developmental information and history of symptoms. This is not always available.

– The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2): The ADOS-2 involves having an individual answer questions and complete tasks to determine whether their presentation is consistent with autism.

– Autism Spectrum Rating Scale (ASRS): An observational measure completed by parents and teachers to provide information about a child’s behaviors. This data is compared to autistic and non-autistic children to determine whether the child’s presentation is consistent with autism.

– The Monteiro Interview Guidelines for Diagnosing the Autism Spectrum, Second Edition (MIGDAS-2): The MIGDAS-2 is an interview assessment that asks about various life experiences and symptoms often seen in autistic individuals.

– The Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Disorders (DISCO): The DISCO uses narrative interview format to get information about communication skills and styles. It can be administered to children or adults.

Autistic people who receive appropriate support may experience lower stress and decreased risk for stress-related illness, mental health issues, and earlier death. As such, identifying appropriate coping or treatment can be important in addressing lower life expectancy.

As autism is a neurodivergence and not a mental illness, it is not something that needs to be “cured” or “fixed,” but appropriate support can increase quality of life.

The goal of treatment must be to help the autistic person identify coping and communication skills that are healthy and appropriate rather than to make them behave in neurotypical ways, as this masking can cause stress and burnout.

Autistic people might benefit from individual therapy to address any comorbid mental health conditions, like trauma disorders, depression, or anxiety. They might also find support in group therapy or support groups, where they can connect with people they relate to and who have had similar experiences.

Typically, autism does not require medication intervention, but autistic people who have other mental health diagnoses might require medication for those conditions.

Autistic people have shorter life expectancy than non-autistic people, partially due to higher risk for genetic and medical issues and partially due to the stress of existing in a world not built for you. Access to appropriate supports can help mitigate this effect. It can also improve quality of life and help individuals manage any comorbid conditions.

The Sack of Rome in May 1527 by the troops of Emperor Charles V—king of Germany, Spain, Naples, and Sicily, and ruler of the Netherlands—was an event of rare violence that left a deep impression during the sixteenth century. An accident of a war opposing a considerable portion of European princes, it partially served as an outlet for religious tensions that had been growing since the late Middle Ages. Protestant but also Catholic soldiers united in a sacred intoxication that announced the religious conflicts to come. The soldiers nevertheless conserved a genuine rationality that lent its full support to a logic of predation. Quickly known throughout Europe, these exactions were interpreted by the vast majority as a religious event: well-deserved punishment for the papal Antichrist or the corruption of the Church, a divine scourge, sacrilege, or an occasion to reconcile Christians within the universal reformation.

Rome, Martyr City of a European Conflict

On May 5, 1527, an imperial army consisting of Spaniards, Flemings, Italians, and Germans encamped in front of Rome. With the Duke of Bourbon at its head, it threatened the continent’s religious capital. He spent over a month living off the land, while seeking to contain the disgruntled troops who had been deprived of pay for over a year.

One must go back two years in time to February 24, 1525, in order to understand the situation. On that morning, imperial troops crushed the French before Pavia: Francis I, who was at the head of his armies, was captured and transferred to the Emperor Charles V in Spain. Italy and Europe were frightened in the face of this overly fortunate prince; a dual league formed around Pope Clement VII to expel the emperor from Northern Italy. Already occupying Parma, Florence, and Modena, the pontiff expanded to Milan and Venice on one side, and to France and England on the other.

Imperial troops counter-attacked without coordination. Ugo Moncada, the Governor of Naples, helped the Cardinal Pompeo Colonna to foment a revolt against the pope in Rome in September 1526. In Cartagena, the Duke of Bourbon set sail for Genoa with a new Spanish army; he was joined in Milan by twelve thousand lansquenets from Germany. In Rome itself, Viceroy Charles de Lannoy played the card of military intimidation, and obtained an agreement with the pope on March 25, 1527. Facing mutiny in Bologna in March, Bourbon began to pillage Romagna on the way to Florence, whose siege would enable him to pay his soldiers. On April 25, the arrival of troops from the league in Florence, in addition to the pope’s breaking of the truce, prompted the duke to change target. He launched his army against Rome, promising the booty of the world’s richest city. Bourbon died during the first assault. Lacking a leader—the emperor’s orders took weeks to arrive, and the young Prince of Orange chosen to succeed the duke did not have his predecessor’s authority—the army rampaged through the city.

The city was subject to looting and violence for eight days. The defenders were quickly eliminated in the fighting. The population was massacred, tortured, and ransomed with no distinction between age or sex, nationality or allegiance. Even the sick in hospices and well-known allies of the imperial cause were killed. Women were raped. Churches and palaces were forced open and emptied of their valuable objects. Archives and libraries were burned. The pope and a part of his court succeeded in shutting themselves in the Castel Sant’Angelo, where they remained safe during the pillaging. The Venetian ambassador described the situation as being worse than hell itself. There were at least twelve thousand deaths, a number that grew with the victims of hunger and epidemics. The violence continued despite the signing of a treaty in June, especially when the army returned from its summer quarters in September.

Sacred Violence and Economy of Predation

The religious violence of the German lansquenets was emphasized in particular. For over ten years, Luther and his disciples had denounced the pope as the Antichrist and Rome as the new Babylon; they vehemently condemned the superstitions of papists such as the worship of saints and relics, the luxury of churches, etc. The exactions of German troops echoed this preaching. In churches they profaned or destroyed relics, tore or smeared images, and stole and dismantled liturgical ornaments. They parodied Catholic pomp by installing a prostitute dressed in priestly clothing on the throne of Saint Peter while singing “Vivat Lutherus pontifex!” in false processions, or while presenting animals for communion. Clergymen were the preferred targets of soldiers, as prelates were killed, humiliated, or sold as slaves, while nuns were raped and monks were castrated.

However, religious violence was not solely the act of Lutherans. In Catholic Europe as well, there was criticism against the corruption of the pope and the Curia, in addition to the prophets and astrologers that announced the imminent punishment of the Church, a prelude to its universal reform and the return of Christ. There had been increasing portents of the scourge to come since 1524. Yet Bourbon and a part of the European knighthood saw themselves as the instrument of God in a world governed by providence. For them the fighting was something mystical, an ordeal in which abandoning oneself to divine will was a way of saving one’s soul and bringing about God’s reign on Earth.

Beyond the religious element, the sack was also a question of money. The occupiers established a ransom economy, in which one had to pay to save one’s life and property. The Italian and imperial general Ferrante Gonzaga paid large sums of money to these men through his mother in order to avoid the pillaging of the family palace. Similarly, many of the acts of torture were carried out by soldiers who wanted their victims to admit where they had hidden their money, or to force them to lend it out. The economy of predation also applied to relics, which were subject to trafficking and speculation.

Europe as Witness

While a few humanists opted for a historical interpretation by likening the event to Alaric’s sack of the City in 410, most observers emphasized the religious and even providentialist view of the Roman tragedy. News of the sack spread throughout Europe, initially in the form of rumors, and later as increasingly precise and coherent witness accounts. The dispatches of ambassadors, which were only known in courts, were succeeded by letters and reports by survivors, as well as by newspapers and occasional printings for broad diffusion. The first of these came from the presses of Venice in mid-May.

In Germany, Luther and the Protestants exulted. The Roman Antichrist and his new Babylon had finally been punished. In Spain, France, and the Netherlands, Erasmists and moderate evangelists were more guarded. Many saw the sack as deserved punishment for the corruption of the Curia and the pope, and believed that the emperor should take advantage to call a council and impose the reformation of the Catholic Church they had been waiting for since the beginning of the century; the scope of the massacres and destruction nevertheless horrified them. Some Catholics shared this opinion, while others were foremost scandalized by the sacrilege committed by the emperor and his ungodly troops.

The imperial chancellery was thus forced to justify itself, despite the divisions among its members. Charles V, who was stupefied, retreated into grief. Gattinara, his Chancellor, urged him to depose the pope and call a universal council, or to repudiate his generals. In late July, the imperial secretary Alonso de Valdes wrote a dual justification of his master: a letter addressed to all Christian princes, and a Dialogue on the Things that Occurred in Rome. These two texts of providentialist and Erasmian inspiration described the sack and its exactions as the act of a mutinous army, with neither leaders nor orders. Emphasizing the deep regret that the event had caused the emperor, Valdes likened it to a divine scourge directed against Clement VII and the corruption of the Curia, which should enable the reconciliation and reformation of all Christianity.

Through both the violence that was unleashed and the interpretations that it prompted, the Sack of Rome prefigured the wars of religion that would soon tear Europe apart. It also represented a threshold beyond which Catholic anti-Romanism, which had been very strong since the fifteenth century, began to decline. For the papacy, it finally marked the beginning of a reconstruction: pagan antiquity—honored at the papal court since the 1490s—was repudiated in favor of biblical antiquity, while the City was taken in hand to become the symbol of the purity of the Church.

Emergency order. Defeat the Metroid of Planet Zebes. Destroy the Mother Brain.

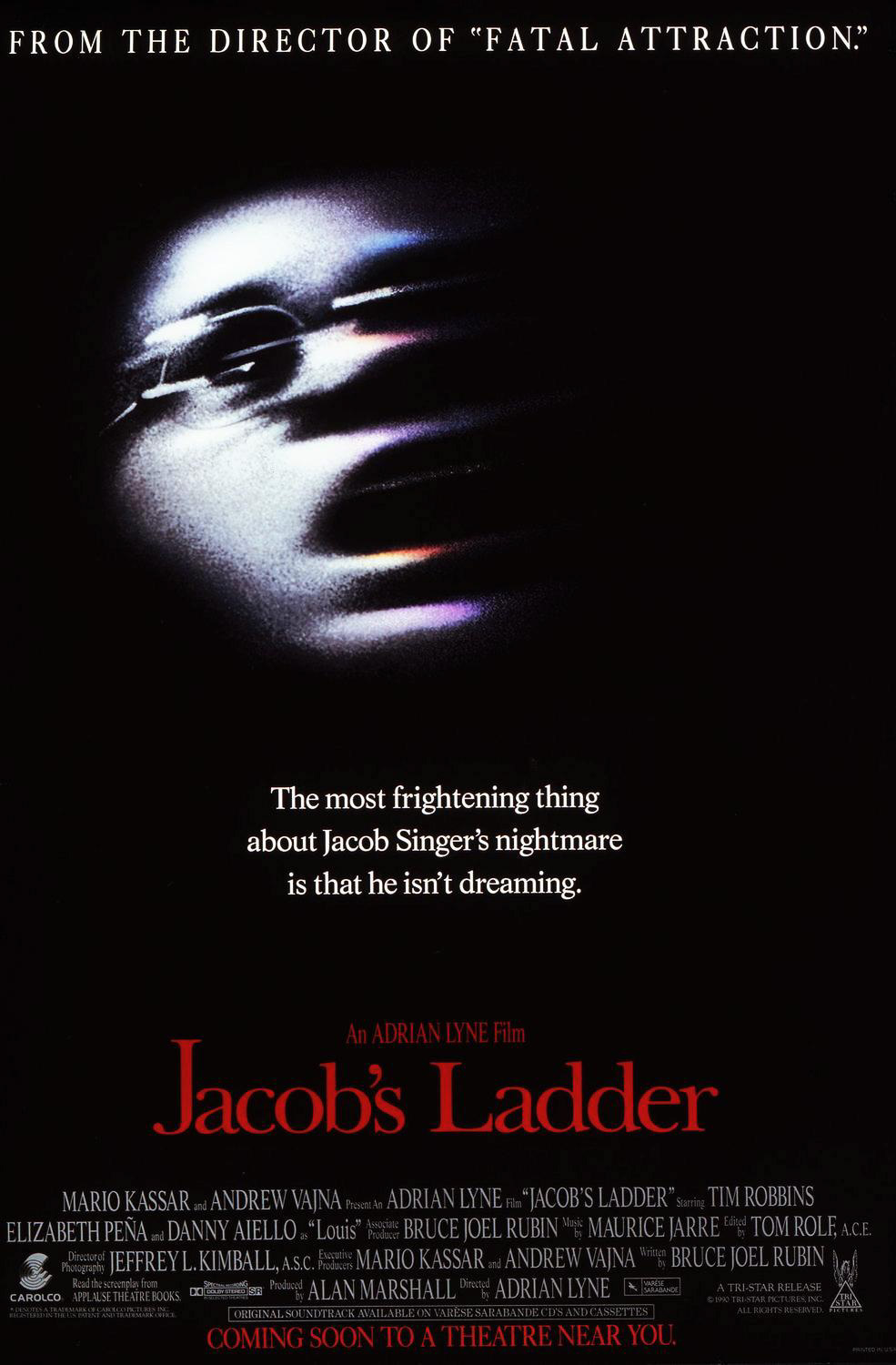

Jacob’s Ladder opens on a hazy, humid evening in Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, 1971. A platoon of U.S. Army soldiers linger in the shade of canvas tents and grass roof huts, smoking, swatting at flies, napping, passing their time in purgatory with grass and childish jokes. Among them is Jacob Singer (Tim Robbins), a private first class his comrades call “Professor” on account of college degrees.

Along with their dog tags, some of the soldiers wear pendants around their neck: a peace symbol, a Star of David, a lucky horseshoe. Jacob’s necklace bears the symbol for ahimsa, the Jain Dharma principle of nonviolence.

In any other film, these details could be considered minor references, but here they are just a few of the many instances in which Jacob’s Ladder uses sacred imagery to tell the story of a broken man desperately clinging to the shattered fragments of his past life.

Without warning, the camp is attacked by an unknown enemy. All hell breaks loose. Some of the soldiers begin to convulse and shake as fire and brimstone rain from the sky. Men are eviscerated and dismembered.

Jacob escapes into the jungle. In a POV shot, he’s ambushed and bayonetted in the gut by an unseen attacker. He falls to the ground, and with a match cut, awakens on a New York City subway train three years later. He’d fallen asleep reading a paperback copy of Albert Camus’s existentialist novella The Stranger and missed his stop. His right hand rests on his abdomen, where he’d been stabbed.

Jacob steps off the train and finds that the exit from his platform is locked, so he must cross over to the other side to get out. As he steps onto the tracks, another train suddenly barrels toward him. He dives out of its way, catching a glimpse of ghostly faces through the windows as it roars by.

Jacob is now a veteran and a postal worker, living in a cozy Brooklyn apartment with his girlfriend Jezebel (Elizabeth Peña). It’s revealed that prior to the war, he’d been a doctor, married to another woman, Sarah (Patricia Kalember), and the father of three children, one of whom, Gabe (Macaulay Culkin), was killed in a tragic auto accident.

The majority of the film’s directly religious references are tied to Judeo-Christian beliefs. (The title itself is a nod to the vision of Old Testament patriarch Jacob, who saw a ladder leading from the earth up to heaven.) Jacob and Jezzie’s apartment is a veritable reliquary of spiritual objects d’art: a Christian cross, crossed again with a pair of swords hangs on the wall next to the window. A replica of Hugo Rheinhold’s Ape with Skull is perched on Jacob’s desk, the open book at the primate’s feet inscribed with the words “Eritis sicut Deus…” which translates to “You will be like God…” The rest of the page is ripped away, omitting the last part of the sentence “…scientes bonum et malum.” Knowing good and evil.

Prayer beads are draped over the shelf on the headboard, next to a candlestick base in the image of Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker (originally conceived as a likeness of poet Dante Alighieri in the sculptor’s masterwork, The Gates of Hell).

Next to the bed is a shelf lined with books like Savage God and The Magical Philosophy, while elsewhere in the apartment A Witches Bible Volume I: The Sabbats, Demonology, The Roots of Evil and Dante’s The Divine Comedy are interspersed with academic texts on sociology and psychology.

These objects provide insight into the psyche and soul of a man concerned with the origins of human nature, and it’s this curiosity that drives him to investigate the relationship between his demonic visions and the revelation that he and his platoon were the subjects of a military psy-op gone wrong.

The filmmakers use several effective techniques to break down the barriers of Jacob’s reality, in particular, editor Tom Rolf’s jump/smash/match cuts between Jacob’s medevac in Vietnam, his horrific visions and his post-war life in New York City.

Many of the demons are portrayed as half-human ghouls with obscured and contorted faces, horns and leathery appendages protruding through broken skin, though some all-out monsters do appear. Makeup effects were supplied by J. Gordon Smith’s Toronto-based FxSmith company. The demons’ vibrating effect was achieved by under-cranking the camera to 4 fps for playback at 24 fps.

“All through the movies you’re dealing with demons and angels and hell and heaven, and I spent a year, maybe more, trying to wrestle with how to do it — how to do a devil with horns and not make people laugh,” said Lyne in a contemporaneous interview (Cinefantastique, Dec ’90). “I tried to make it all human-based — sort of thalidomidey — fleshy, horns from the bone, a tail that looks a little like a schlong. I didn’t want these things easily dismissed as too familiar. I did a lot of shaking, vibrating, tortured things.”

Religious symbolism is woven so throughly into the tapestry of the film’s narrative that one begins to recognize familiar images where they were perhaps not intended, such as the scene were Jacob goes into shock after witnessing a vision of Jezzie and a demon. His temperature skyrockets, and Jezzie rallies the help of two neighbors to lift Jacob into a bathtub full of ice water.

The camera is tight on Jacob’s flushed, passionate expression. His head lolls to one shoulder. His outstretched arms are supported by the neighbors as Jezzie looms anxiously in the backround. When they lift him into the tub their arms fully encircle his body, the way Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus lower the body of Christ down from the cross in the popular Christian motif. (A similar mood is struck in Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ.)

Jacob’s only solace is in his visits with Louis (Danny Aiello), the smiling, rotund chiropractor whom Jacob describes as an “overgrown cherub.” Louis’s office is a sanctuary filled with soft white light streaming in through a set of bay windows and Tiffany stained glass.

Jacob’s inquiries into the possibility that he and the other soldiers were unwilling test subjects in a murderous wargame gets the attention of U.S. Government agents, who ambush and threaten him. Jacob escapes capture by throwing himself from their moving vehicle, but severely injures his back. He’s taken to a hospital, the bowels of which is populated with a host of tortured souls.

“I tried to use images from Francis Bacon — tortured, blurred shots, red streaks and sharp pieces which, when you freeze frame this stuff, looks just like Bacon’s drawings,” said Lyne (Cinefantastique, Dec ’90).

Jacob is strapped to a reclining operating table and his head is screwed into a medical halo. The operating lamp bathes him with light, which reflects off his body and onto the attending doctors lurking at the edge of darkness in a macabre twist on Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp. Jezzie, in a surgical gown, preps a wicked-looking syringe then hands it to an eyeless demon, who plunges the giant needle into the middle of Jacob’s forehead in an attempt to purge his memories and ultimately, his will to live.

Cinematographer Jeffrey L. Kimball, ASC’s striking photography possesses the tones and textures of a Renaissance-era painting. Optically, the film has a deep-focus quality, with atmospheric perspective used to achieve a sense of depth by contrasting dark foregrounds and light backgrounds filled with steam, haze and smoke.

Additionally, light is diffused at the source, creating a sfumato effect through which tones and colors gradually shade together to produce soft outlines and hazy forms.

Chiaroscuro lighting enhances textural qualities with deep shadows.

Jacob awakes in the hospital, doped up and in traction, unsure of what he’s experiencing is real or a dream. Louis storms in, all righteous fury. Untangling Jacob from his harnesses, he cries “Why don’t you just burn him at the stake?” Louis transfers him from the hospital bed to a wheelchair and whisks him back to the safety of his office. “I was in hell,” Jacob murmurs. “I don’t want to die.”

Louis cracks a knowing smile. “Eckhart saw hell, too,” he says, referring to the thirteenth century German Catholic theologian, philosopher and mystic. “The way he sees it, if you’re frightened of dying and you’re holding on, you’ll see devils tearing your life away. But if you’ve made your peace, the devils are really angels freeing you from the earth. It’s just a matter of how you look at it.”

Carl G. Jung — a Swiss psychiatrist whose ideas the filmmakers (and Jacob) are almost certainly aware of — writes in his 1964 essay Approaching the Unconscious that symbols point to something working deep in the human unconscious to conjure the vast, significant mysteries of existence. When signs, like an effigy or image of the human body, are imbued with mystery, they become symbols because they now stand for something beyond the object itself, though their true meaning remains elusive and subjective.

Back at the apartment, Jacob sorts through the contents of an old cigar box, a personal collection of sacred objects he’s held on to over the years: honorable discharge papers, a Master of Arts degree from Brooklyn College, dogtags (the religious preference is Jewish) and a letter from Gabe.

In one of the film’s most visually and thematically darkest scenes, Jacob meets with Michael (Matt Craven), a former chemist in the Army’s “Ladder” program, who reveals the truth of what happened on the day Jacob’s platoon was attacked: in a drug-induced craze, the soldiers turned against each other, their lives sacrificed on the altar of war.

Thus enlightened, Jacob gives a taxicab driver all the money in his pocket to take him “home,” back to the apartment he once shared with Sarah. Rosary beads jangle on the dashboard as the cab cuts through the dense night fog like Charon on the River Styx.

A doorman at wrought iron gates welcomes Jacob as an old friend or St. Peter might. Past halls of white marble and crown molding, Jacob finds tableaus of unfinished homework and half-eaten dessert, a life in framed photographs on the piano.

Jacob sits on the couch in quiet contemplation as rain falls outside and a sharp blue light cuts into the room from a low angle. In a montage set to a slowly beating heart, the most significant memories of Jacob’s life come flooding back in grainy 16mm.

The heartbeat stops. The rain has ended. Jacob awakens and finds Gabe sitting on the steps, bathed in heavenly morning light. The little boy takes his father by the hand and leads him upstairs, and the image dips to white.

We are back in Vietnam. Having succumbed to his injuries, Jacob lies dead on a stretcher in a field hospital, his prone body still enough to have been carved from stone, with the faint hint of a smile upon his face. “He looks kind of peaceful,” says a medic as he removes one of Jacob’s dog tags.

Religion uses iconography to tell stories of life, death and redemption where traditional language is insufficient and personal experience with a system of belief isn’t required. Symbols are necessarily universal as well as mysterious, and only when coupled with a text or image or transferred to a personal object or sign do they become specific. Jacob’s Ladder inverts this formula by taking the universal experience of dying — in a narrative lifted from The Tibetan Book of the Dead — and using specific symbols to imbue it with a deeper, more personal meaning.

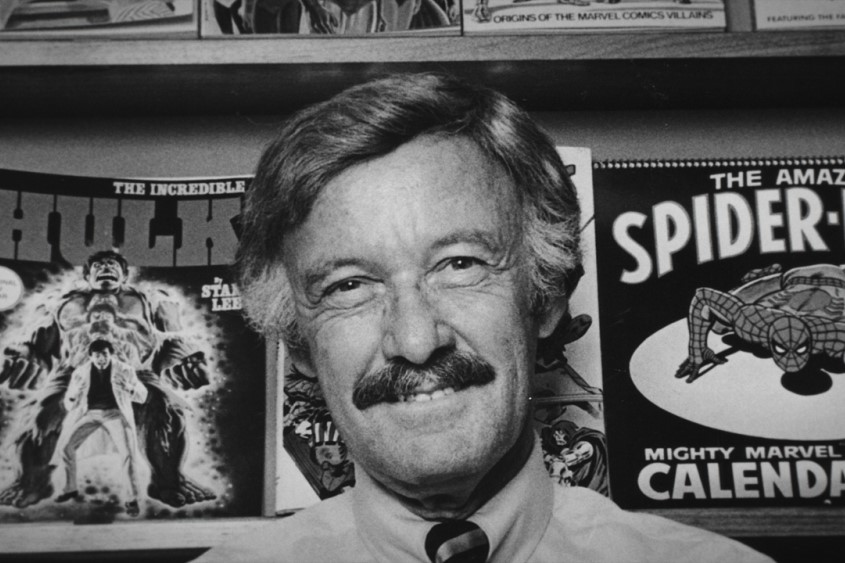

Neal Kirby, son of the seminal Marvel Comics artist and writer Jack Kirby, has shared a statement expressing his distaste with Disney+’s new documentary spotlighting the life of Stan Lee.

Credited as one of the leading creators of Marvel Comics, Lee’s life and legacy are given a detailed exploration through the doc, which premiered on the streamer on June 16. Kirby released a skeptical statement about the film through the Twitter account of his daughter, Jillian Kirby.

“It should be noted and is generally accepted that Stan Lee had a limited knowledge of history, mythology, or science,” Kirby wrote. “On the other hand, my father’s knowledge of these subjects, to which I and many others can personally attest, was extensive. Einstein summed it up better; ‘More the knowledge, lesser the ego. Lesser the knowledge, more the ego.’”

Kirby’s lengthy denouncement continues by calling into question Lee’s involvement in the creation of many Marvel characters in the early-to-mid 1960s. “You will see Lee’s name as a co-creator on every character, with the exception of the Silver Surfer, solely created by my father. Are we to assume Lee had a hand in creating every Marvel character? Are we to assume that it was never the other co-creator that walked into Lee’s office and said, ‘Stan, I have a great idea for a character!’ According to Lee, it was always his idea.”

Kirby also highlights that Lee took major credit for creating the Fantastic Four “with only one fleeting reference” to his father. He also claims that the Fantastic Four was initially created by Jack for DC in the “Challengers of the Unknown” comic. Kirby goes on by stating that Ben Grimm (The Thing) was named after his father’s real name, Benjamin, and Sue Storm was named after his daughter, Susan.

Episode 165 – We’re back and we bring you an overview of the PS2 and some of it’s games. This is not a greatest hits compilation. What are some of your favorite PS2 games? What does the system mean to you?