(Author’s note: In this article I rely heavily on the evidence cited in the research of Mark Tauger of West Virginia University. Tauger has spent his professional life studying Russian and Soviet famines and agriculture. He is a world authority on these subjects, and is cordially disliked by Ukrainian nationalists and anticommunists generally because his research explodes their falsehoods. )

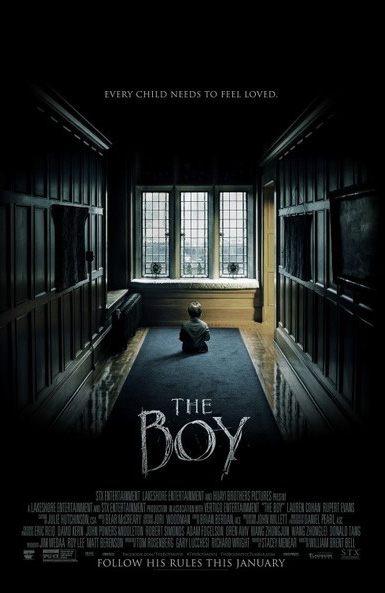

The Ukrainian nationalist film “Bitter Harvest” propagates lies invented by Ukrainian nationalists. In his review Louis Proyect propagates these lies.

Proyect cites Jeff Coplon’s 1988 Village Voice article “In Search of a Soviet Holocaust: A 55-Year-Old Famine Feeds the Right.” In it Coplon shows that the leading “mainstream” anticommunist Western experts on Soviet history rejected any notion of a deliberate famine aimed at Ukrainians. They still reject it. Proyect fails to mention this fact.

There was a very serious famine in the USSR, including (but not limited to) the Ukrainian SSR, in 1932-33. But there has never been any evidence of a “Holodomor” or “deliberate famine,” and there is none today.

The “Holodomor” fiction was invented in by Ukrainian Nazi collaborators who found havens in Western Europe, Canada, and the USA after the war. An early account is Yurij Chumatskij, Why Is One Holocaust Worth More Than Others? published in Australia in 1986 by “Veterans of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army” this work is an extended attack on “Jews” for being too pro-communist.

Proyect’s review perpetuates the following falsehoods about the Soviet collectivization of agriculture and the famine of 1932-33:

- That in the main the peasants resisted collectivization because it was a “second serfdom.”

- That the famine was caused by forced collectivization. In reality the famine had environmental causes.

- That “Stalin” – the Soviet leadership – deliberately created the famine.

- That it was aimed at destroying Ukrainian nationalism.

- That “Stalin” (the Soviet government) “stopped the policy of “Ukrainization,” the promotion of a policy to encourage Ukrainian language and culture.

None of these claims are true. None are supported by evidence. They are simply asserted by Ukrainian nationalist sources for the purpose of ideological justification of their alliance with the Nazis and participation in the Jewish Holocaust, the genocide of Ukrainian Poles (the Volhynian massacres of 1943-44) and the murder of Jews, communists, and many Ukrainian peasants after the war.

Their ultimate purpose is to equate communism with Nazism (communism is outlawed in today’s “democratic Ukraine”); the USSR with Nazi Germany; and Stalin with Hitler.

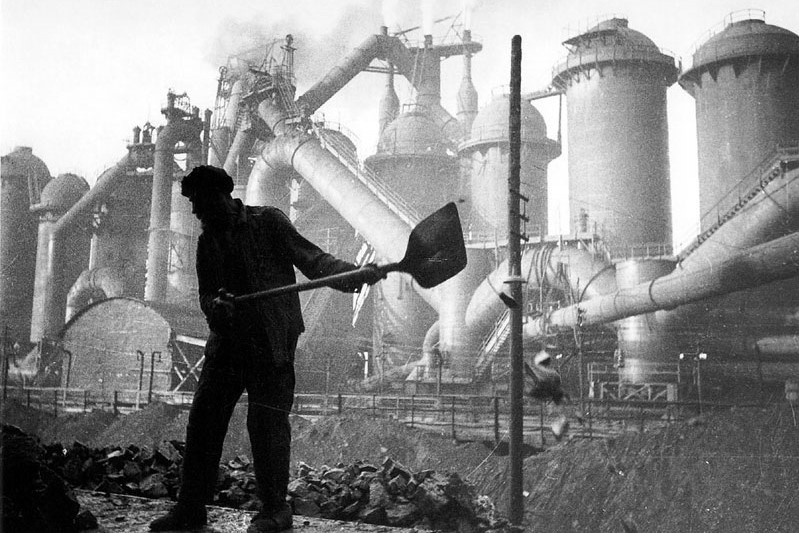

Collectivization of Agriculture – The Reality

Russia and Ukraine had suffered serious famines every few years for more than a millennium. A famine accompanied the 1917 revolution, growing more serious in 1918-1920. Another serious famine, misnamed the “Volga famine,” struck from 1920-21. There were famines in 1924 and again in 1928-29, this last especially severe in the Ukrainian SSR. All these famines had environmental causes. The medieval strip-farming method of peasant agriculture made efficient agriculture impossible and famines inevitable.

Soviet leaders, Stalin among them, decided that the only solution was to reorganize agriculture on the basis of large factory-type farms like some in the American Midwest, which were deliberately adopted as models. When sovkhozy or “Soviet farms” appeared to work well the Soviet leadership made the decision to collectivize agriculture.

Contrary to anticommunist propaganda, most peasants accepted collectivization. Resistance was modest; acts of outright rebellion rare. By 1932 Soviet agriculture, including in the Ukrainian SSR, was largely collectivized.

In 1932 Soviet agriculture was hit with a combination of environmental catastrophes: drought in some areas; too much rain in others; attacks of rust and smut (fungal diseases); and infestations of insects and mice. Weeding was neglected as peasants grew weaker, further reducing production.

The reaction of the Soviet government changed as the scope of the crop failure became clearer during the Fall and Winter of 1932. Believing at first that mismanagement and sabotage were leading causes of a poor harvest, the government removed many Party and collective farm leaders (there is no evidence that any were “executed” like Mykola in the film.) In early February 1933 the Soviet government began to provide massive grain aid to famine areas.

The Soviet government also organized raids on peasant farms to confiscate excess grain in order to feed the cities, which did not produce their own food. Also, to curb profiteering; in a famine grain could be resold for inflated prices. Under famine conditions a free market in grain could not be permitted unless the poor were to be left to starve, as had been the practice under the Tsars.

The Soviet government organized political departments (politotdely) to help peasants in agricultural work. Tauger concludes: “The fact that the 1933 harvest was so much larger than those of 1931-1932 means that the politotdely around the country similarly helped farms work better.” (Modernization, 100)

The good harvest of 1933 was brought in by a considerably smaller population, since many had died during the famine, others were sick or weakened, and still others had fled to other regions or to the cities. This reflects the fact that the famine was caused not by collectivization, government interference, or peasant resistance but by environmental causes no longer present in 1933.

Collectivization of agriculture was a true reform, a breakthrough in revolutionizing Soviet agriculture. There were still years of poor harvests — the climate of the USSR did not change. But, thanks to collectivization, there was only one more devastating famine in the USSR, that of 1946-1947. The most recent student of this famine, Stephen Wheatcroft, concludes that this famine was caused by environmental conditions and by the disruptions of the war.

Proyect’s False Claims

Proyect uncritically repeats the self-serving Ukrainian fascist version of history without qualification.

- There was no “Stalinist killing machine.”

- Committed Party officials were not “purged and executed.”

- “Millions of Ukrainians” were not “forced into state farms and collectives.” Tauger concludes that most peasants accepted the collective farms and worked well in them.

- Proyect accepts the Ukrainian nationalist claim of “3-5 million premature deaths.” This is false.

Some Ukrainian nationalists cite figures of 7-10 million, in order to equal or surpass the six million of the Jewish Holocaust (cf. Chumatskij’s title “Why Is One Holocaust Worth More Than Others?”). The term “Holodomor” itself (“holod” = “hunger”, “mor” from Polish “mord” = “murder,” Ukrainian “morduvati” = “to murder) was deliberately coined to sound similar to “Holocaust.”

The latest scholarly study of famine deaths is 2.6 million (Jacques Vallin, France Meslé, Serguei Adamets, and Serhii Pirozhkov, “A New Estimate of Ukrainian Population Losses during the Crises of the 1930s and 1940s,” Population Studies 56, 3 (2002): 249–64).

- Jeff Coplon is not a “Canadian trade unionist” but a New-York based journalist and writer, The late Douglas Tottle’s book Fraud, Famine and Fascism, a reasonable response to Robert Conquest’s fraudulent Harvest of Sorrow, was written (as was Conquest’s book) before the flood of primary sources from former Soviet archives released since the end of the USSR in 1991 and so is seriously out of date.

- Walter Duranty’s statement about “omelets” and “eggs” was not said “in defense of Stalin” as Proyect claims but in criticism of Soviet government policy:

But — to put it brutally — you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs, and the Bolshevist leaders are just as indifferent to the casualties that may be involved in their drive toward socialization as any General during the World War who ordered a costly attack in order to show his superiors that he and his division possessed the proper soldierly spirit. In fact, the Bolsheviki are more indifferent because they are animated by fanatical conviction. (The New York Times March 31, 1933)

Evidently Proyect simply copied this canard from some Ukrainian nationalist source. Garbage In, Garbage Out.

- Andrea Graziosi, whom Proyect quotes, is not a scholar of Soviet agriculture or the 1932-33 famine but an ideological anticommunist who assents to any and all anti-Soviet falsehoods. The article Proyect quotes is from Harvard Ukrainian Studies, a journal devoid of objective research, financed and edited by Ukrainian nationalists.

- Proyect refers to “two secret decrees” of December 1932 by the Soviet Politburo that he has clearly not read. These stopped “Ukrainization” outside the Ukrainian SSR. Within the Ukrainian SSR “Ukrainization” continued unabated. It did not “come to an end” as Proyect claims.

- Proyect cites no evidence of a Soviet “policy of physically destroying the Ukrainian nation, especially its intelligentsia” because there was no such policy.

A Triumph of Socialism

The Soviet collectivization of agriculture is one of the greatest feats of social reform of the 20th century, if not the greatest of all, ranking with the “Green Revolution,” “miracle rice,” and the water-control undertakings in China and the USA. If Nobel Prizes were awarded for communist achievements, Soviet collectivization would be a top contender.

The historical truth about the Soviet Union is unpalatable not only to Nazi collaborators but to anticommunists of all stripes. Many who consider themselves to be on the Left, such as Social-Democrats and Trotskyists, repeat the lies of the overt fascists and the openly pro-capitalist writers. Objective scholars of Soviet history like Tauger, determined to tell the truth even when that truth is unpopular, are far too rare and often drowned out by the chorus of anticommunist falsifiers.

Sources: Mark Tauger’s research, especially “Modernization in Soviet Agriculture” (2006); “Stalin, Soviet Agriculture, and Collectivization” (2006); and “Soviet Peasants and Collectivization, 1930-39: Resistance and Adaptation.” (2005), all available on the Internet. More of Tauger’s articles are available at this page: https://www.newcoldwar.org/archive-of-writings-of-professor-mark-tauger-on-the-famine-scourges-of-the-early-years-of-the-soviet-union/

See also Chapter I of my book Blood Lies; The Evidence that Every Accusation against Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union in Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands Is False (New York: Red Star Press, 2013), at http://msuweb.montclair.edu/~furrg/research/furr_bloodliesch1.pdf

On the 1946-47 famine see Stephen G. Wheatcroft, “The Soviet Famine of 1946–1947, the Weather and Human Agency in Historical Perspective.” Europe-Asia Studies, 64:6, 987-1005.