Toshiba’s 35-year run in the laptop business is at an end, but what a journey it has been.

Toshiba

Toshiba was among the first vendors to offer consumers personal computers that were small and affordable enough for our homes.

In a time where the phones in our pockets have far more power than PCs ever could hope to have back in the 1980s, it seems odd to think of when laptops were out of the reach of most of us — but this is one industry that has completely transformed over the past few decades.

Let’s take a look at Toshiba’s PC career, starting with the first consumer-grade laptop made available in Europe, until the present day.

1985: The world’s first laptop?

In the 1970s, hobbyists created a market for home PC assembly kits, leading to the creation of Apple II in 1977, various Sony desktops, and the IBM PC in 1981.

Toshiba was falling behind in this evolving market, having focused on Japanese word processors. While the company had formed a PC unit, the department was running on a deficit and Toshiba was on the verge of giving up.

However, according to the Toshiba Museum, the firm believed a PC focused on “mobility, smaller size, and power-saving” could save the day — and it did.

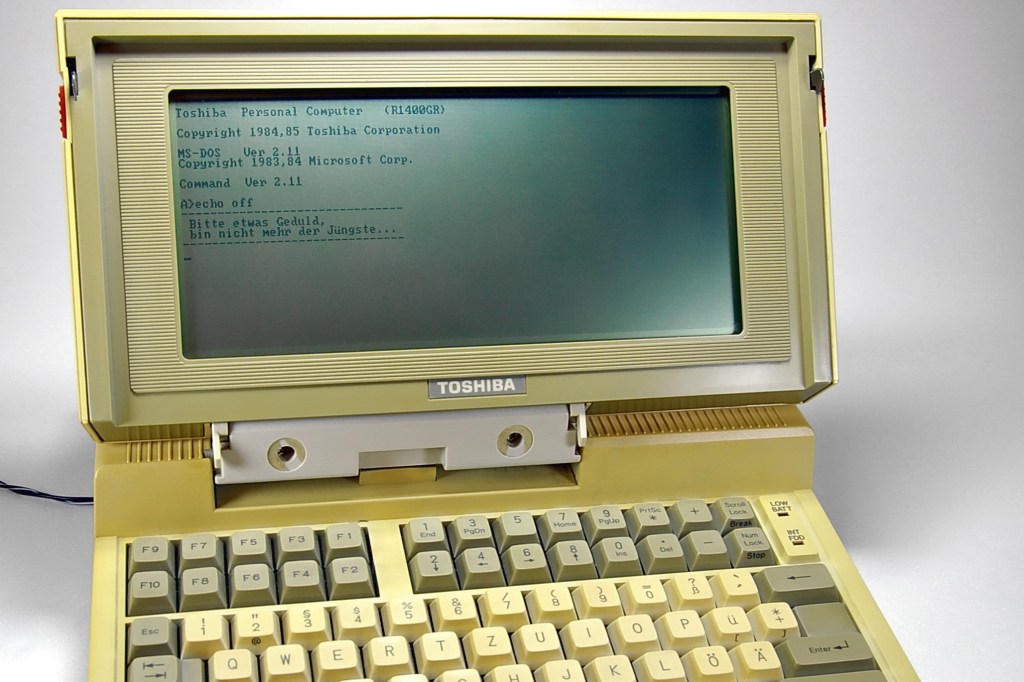

In 1985, the T110 debuted in Europe, described by Toshiba as the “world’s first laptop PC.” The T110 wasn’t perfect — using a 3.5-inch floppy disk drive rather than the 5-inch standard at the time — and cost 500,000 yen ($4,700). However, at least 10,000 were sold, giving Toshiba the drive to develop new models.

1986, 1987: Toshiba T3100, T5100

The Toshiba T3100, a PC equipped with a 640 x 400 resolution, 9.6-inch orange gas plasma screen, operated on the Toshiba MS-DOS 2.11/3.2 OS — as Microsoft Windows builds were not yet mainstream — and came with an 80286 CPU running at 8MHz, as well as a 3.5-inch 20MB hard drive.

Basic setups offered 640KB memory, but this could be upgraded to 2.6MB. The T3100, weighing 15 pounds, was considered portable back then.

In 1987, the T5100 Desktop Portable 386 came on to the scene. Toshiba said it was the only portable PC using the Intel 80386 engine, which at the time was more commonly found in larger and more powerful desktop computers.

Weighing in the same as the T3100, the MS-DOS 3.2 PC (.PDF) was geared towards business users who needed computers able to work with office applications and databases.

An 8/16Mhz 80386 processor, an internal 40MB Winchester hard disk, a 1.44MB 3.5-inch floppy, 2MB RAM — upgradable to 4MB — and a 640 x 400 resolution gas plasma display completed the setup.

1989/1990: DynaBook J-3100SS

Dynabook, Toshiba’s PC arm, has been around for decades and a product of note, released between 1989 and 1990 was the DynaBook J-3100SS.

The J-3100SS was an A4-size notebook PC that used an LCD 640 x 400-pixel display and was far lighter than previous designs, coming in at 2.7kg. An Intel 80386 processor and 1.5MB RAM were standard — but this could be upgraded to a maximum of 3.5MB — as well as a 3.5-inch floppy and a 20MB hard drive.

1992 to 2000

From 1992 to 2000, Toshiba released a number of laptops improving in function and specifications every year.

Released in 1992, for example, the DynaBook V486 J-3100XS portable PC featured a memory boost, coming in with 4MB as standard but upgradeable to 12MB. The DynaBook EZ486P was one of the few portable PC models sporting an inbuilt printer, whereas the DynaBook GT-R590, introduced in 1995, came with two operating systems pre-installed; Microsoft Windows 3.1 and Windows 95.

As we moved into 2000, the DynaBook DB70P/5MC was developed in deference to a growing demand for devices able to support media playback. It’s a world away from our current consumption of streamed media, but back then, CD-ROM, CD-R/RW, and DVD-ROMs were sought after, and this laptop was marketed as the first of its kind able to write to CD as well as play DVDs.

2001: Toshiba Satellite Pro 4600

A year later, Toshiba launched the Satellite Pro range, a line of laptops (.PDF) intended for business and power users. The Satellite Pro 4600 series was offered with a range of Intel processors, a wireless LAN module, and accessories designed to switch from a laptop to desktop setup in the office.

2005: Portégé M100

If you explore Toshiba’s laptop history, you can’t forget the Portégé range. In 2005, the launch of the Portégé M100 signaled a move to Intel Pentium M and Intel 855 chipsets, coming in as a thinner and lighter model than previous business PCs.

This laptop, too, sported a far better battery life than its precessors — going from roughly two to four hours on a single charge — and also came with 40GB storage and 256MB RAM.

2008: The gaming scene

During its long stint in the laptop industry, Toshiba also dipped a toe into the gaming world. In 2008, Toshiba launched the Qosmio X300 series, stylish laptops designed with gamers in mind.

The flagship 17-inch laptop sported an Intel Core 2 Duo P8600 and Intel Core 2 Extreme QX9300 processor, NVIDIA GeForce 9700M GTS/9800M GTS SLI graphics, 4GM RAM, and 520GB storage.

2016: Business pivot

From 2008 to 2016, Toshiba developed a range of consumer and business laptops, improving over time in processors, memory, chassis, and speed.

However, Toshiba began to break away from consumer models in 2016 to focus on the enterprise market, as shown with the 2017 release of the Toshiba Portege X20W-D.

The 1.1kg Toshiba Portege X20W-D is a 2-in-1 laptop and tablet, sporting a 12.5-inch 1,920 x 1,080-pixel display, an Intel Core i7 processor, 16GB RAM, Intel HD Graphics, and the Windows 10 operating system.

2018: Sharp

In 2018, Toshiba sold its PC business to Sharp for $36 million, with 80.1% of shares transferred over.

The company’s PC unit also rebranded to Dynabook, pivoting to enterprise-ready laptops including the TECRA X40-E, Portégé X30-E, and Portégé X20W-E.

2020: End of an era

In August, Toshiba formally exited the laptop business with the final transfer of its remaining Dynabook shares, 19.9%, to Sharp.

The Japanese tech giant has weathered accounting scandals, nuclear power plant lawsuits, and drastic restructuring efforts to survive, and now, the company sees the future in industrial and energy solutions, digital signage, and the manufacture of IT components including semiconductors.

There is no limit to the slanders spewed by U.S. corporate media – from so-called journalists to filmmakers to comedians – against North Korea, the Democratic Peoples Republic of Korea. “The racist and inaccurate discourse around the DPRK helps justify the almost daily military operations the US backs in South Korea.” The 60-year long propaganda campaign is “part and parcel of the US imperialist agenda to militarize the Asia Pacific.”

The corporate media is the mouthpiece of US imperialism. More specifically, the Hollywood arm of the corporate media is tasked with promoting the US-Western imperialist way of life as profitable “entertainment.” Seth Rogan’s new film fits snugly into this mold. In The Interview, Rogan and James Franco play CIA recruits assigned with the job of assassinating the current leader of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), Kim Jong-un. This overtly cruel and monstrous plot line should come as no surprise to anyone following US imperialism’s decades long war against Korea.

The Korean War is labeled a “forgotten war” by the US corporate media and political class. In reality, the US imperialist ruling class has done everything it can to erase the stain of the Korean War from popular memory. The US imperialist war on Korea formally began in 1950 after the US violated a temporary (three year) political agreement with the Soviet Union to peacefully divide Korea along the 38th parallel. Instead of abiding by the agreement, the US installed dictator Syngman Rhee in the South and armed it to the teeth at the tune of a half billion US dollars. Rhee used the funds to slaughter hundreds of thousands of guerrilla forces in the North. Despite this, Korean independence and socialist forces counter-attacked and liberated Seoul, the capital of South Korea. Washington, in a scramble to protect its interests in South East Asia from socialist construction and Chinese alliance, agreed to reserve 12 billion dollars for a land invasion in Korea.

During the invasion, the US dropped 420,000 bombs on the capital of the DPRK, Pyongyang. The bombing campaigns left large percentages of Northern Korea without homes or basic infrastructure. More than a million Koreans died. Despite heavy losses, the resistance of the Korean Peoples Army and the socialist Korean Workers Party forced the US into an armistice agreement in 1953. To this day, the US refuses to sign a peace treaty and maintains a militarized presence in the South, where 29,000 US ground troops are currently stationed. The US government also enforces economic sanctions on the DPRK. US sanctions exacerbated the DPRK’s food insecurity crisis in the early 90’s after the destabilization of the Soviet Union and socialist bloc cut off much of the nation’s access to international trade and finance.

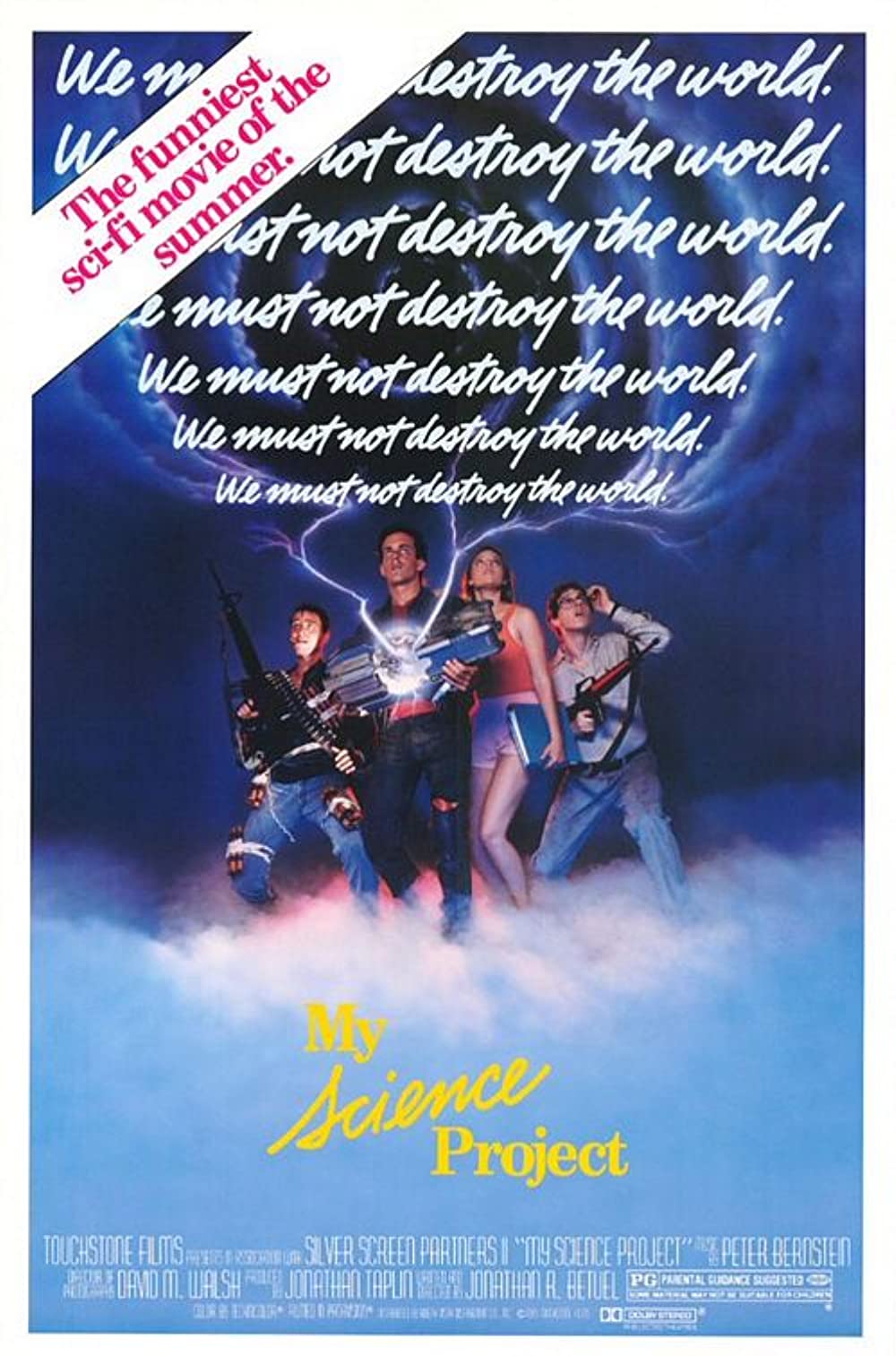

US imperialism’s assault on Korea and the DPRK is not a “forgotten war”, but rather, a distorted one. The majority of people in the US obtain knowledge of the DPRK through the lens of the US imperialist corporate media. The Interview is just one of many Hollywood films that have dehumanized the DPRK’s leadership and socialist system in the interests of US empire. The 2004 film Team America: World Police portrayed Kim Jong-il as a literal cockroach whose insecurity fueled ambitions for world domination. In 2012 and 2013, the movies Red Dawn and Olympus Has Fallen each parroted Washington’s image of a militarist North Korea hell-bent on waging war on the US mainland.

To compliment these false and racist depictions of the DPRK, corporate journalism in the US repetitiously reports unverified instances of the DPRK repressing its own people and threatening the US with nuclear war. US imperial slander occurs so often that the fallacies only become more ridiculous. This recently took shape in the US media’s recent report of Kim Jong-un’s supposed mandate that the entire male population of the DPRK cut its hair in Un’s particular style. Of course, such slander never amounts to fact, but rather a politicized gossip partaken by the war-mongering imperialist ruling class and consumed by the rest of us.

Corporate media slander of the DPRK helps fulfill two key objectives for US imperialism. The racist and inaccurate discourse around the DPRK helps justify the almost daily military operations the US backs in South Korea. In contrast to Western media narrative, it is the US’s puppet state in South Korea that conducts regular military exercises, all of which directly or indirectly target the DPRK. In addition to military destabilization, the US corporate media seeks to ideologically erase the heroic victories of Korean socialism. Despite being set ablaze by US bombs during the US invasion of 1950-53 and sanctioned from needed economic assets, the DPRK possesses a growing socialist economy. Housing, education, and healthcare are human rights provided to all. The food insecurity the DPRK experienced in the 90’s has been reduced mightily and the corporate media knows it, as evidenced by its recent avoidance of the issue as a talking point of DPRK demonization.

The US desperately needs to maintain hegemony in the region by keeping Korea divided and disallowing the DPRK to expand political influence in the region through national unity. China’s rise in the east has counterbalanced US imperial power with a more powerful economic system. The destabilization of the DPRK is part and parcel of the US imperialist agenda to militarize the Asia Pacific in an attempt to slow down inevitable crisis and collapse. Corporate media depictions of the DPRK need to be placed within the context of US imperial decline. One of the challenges for the left in this period is to fight the US’s racist narrative of the DPRK, not only for the sake of the Korean people but also for all people struggling to dig the final grave for US imperialism.

Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street (Herzen Street from 1920 to 1993) is a street in the Central Administrative District of Moscow. It passes from Manezhnaya Square to Kudrinskaya Square, and lies between Tverskaya Street and Vozdvizhenka, parallel to them. The numbering of houses begins from Manezhnaya Square. In 1920, in connection with the 50th anniversary of the death of the writer and revolutionary democrat Alexander Herzen, it was renamed as Herzen Street. In 1993, the historical name was returned to the street. In 1997, the main part of the buildings of the street from the Nikitsky Gate Square to the Garden Ring was included in the Povarskaya-Bolshaya Nikitskaya protected area.

Grover Carr Furr III (born April 3, 1944) is an American professor of Medieval English literature at Montclair State University, best known for his books on Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union. He has published many books on this subject.

The death of Mikhail Gorbachev has led to a great unfolding of information in the international press. In several headlines he is highlighted as the last Soviet leader; strictly speaking, he was not, since he led the final stage of capitalist restoration in the former USSR, an aspect totally contrary to Sovietism.

Gorbachev assumed the functions of General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, CPSU, in March 1985 and shortly thereafter was named President of the USSR. It was a time when economic, political, social and moral problems took on great dimensions in that country. In the 1970s, the growth rate of national income fell by more than 50% and in the early 1980s it almost reached zero. Corruption could not be stopped; there was talk of a “second economy” to designate what is known as the “black market,” in which officials at the highest level of the State and leaders of the party were involved. The health system was practically in ruins; housing was overcrowded; the rates of alcoholism in the population were high; people’s life expectancy was reduced and mortality was on the rise. There were many more problems.

The bases of capitalism resurfaced in the former USSR with the coup d’état carried out by Nikita Khrushchev and his clique in 1956, after the death of Joseph Stalin (1953). Over the years, the successes achieved by socialism in all fields while Lenin and Stalin were at the head of the state were undermined and capitalist laws and forms of production were imposed. So much so that Leonid Brezhnev (who succeeded Khrushchev) said that “no one lives on their salary alone,” referring to the existence of the “black market” and the social strata that depended on private economic activity for their income.

Gorbachev, when he assumed the leadership of the party and state, obviously did not present himself as an open promoter of capitalist re-establishment; he said that his purpose was to establish an “efficient, productive and democratic socialism,” and thus led to the disintegration of the USSR.

The economic and political reforms that brought the anti-socialist process initiated by revisionism four decades earlier to the highest point, were made official in July 1987. A year earlier they were approved at a Party congress, but as early as 1984, in a speech to the ideological working group of the Central Committee of the Party, Gorbachev raised the need for an information opening (glasnost) and the restructuring of the economic system (perestroika).

Gorbachev’s plan sought to establish a capitalist market economy, eliminate control over state enterprises, which could now determine what to produce, how much to produce and the prices in the market based on consumer demands; a new law on cooperatives restored private ownership to companies in services, manufactures and sectors linked to foreign trade; foreign trade was liberalized. This led to deindustrialization and the privatization of state-owned enterprises. In 1994, when the USSR no longer existed, 70% of the assets in Russia came from the private sector.

Hand in hand with the pro-capitalist reforms was glasnost (transparency), which supposedly had the purpose of democratizing information, but in reality it was a means to open the floodgates to an open and furious anti-communist propaganda, driven by the most degenerate and pro-restoration sectors. The historical distortion of the process of building socialism in the USSR was one of the targets and, particularly, the unfounded attacks against Stalin were accentuated.

Gorbachev defined perestroika as a revolution within the revolution, aimed at achieving more socialism and more democracy; in reality it was a counter-revolution within the counter-revolution. The economic and social problems deepened, the USSR fell into political chaos, the demands of the workers and the people were lit up on all sides, and some Soviet republics demanded to secede.

On December 25, 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev broadcast a live message on television, announcing his resignation from the presidency of the Republic. It was a formality; in fact he had no control over the situation in the country; days earlier the Washington Post called him the leader of a kingdom in the air.

The international bourgeoisie loudly applauded what Gorbachev did. None other than George Bush Sr. said that “the revolutionary transformation of a totalitarian dictatorship and the liberation of its people from its suffocating embrace” had taken place. If the most powerful imperialist head of state on the planet said that, it is because Gorbachev’s services to world capitalism were enormous.