As the quest for natural and effective health supplements continues, a combination that has been gaining attention is Liposomal Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) plus Luteolin. This duo is touted for its potential to offer a range of health benefits, from reducing inflammation to protecting neurological function. In this article, we delve into the science behind these compounds and explore the health benefits they may provide.

Understanding Liposomal PEA and Luteolin

Before we examine the benefits, it’s important to understand what these compounds are and how they work.

What is Liposomal PEA?

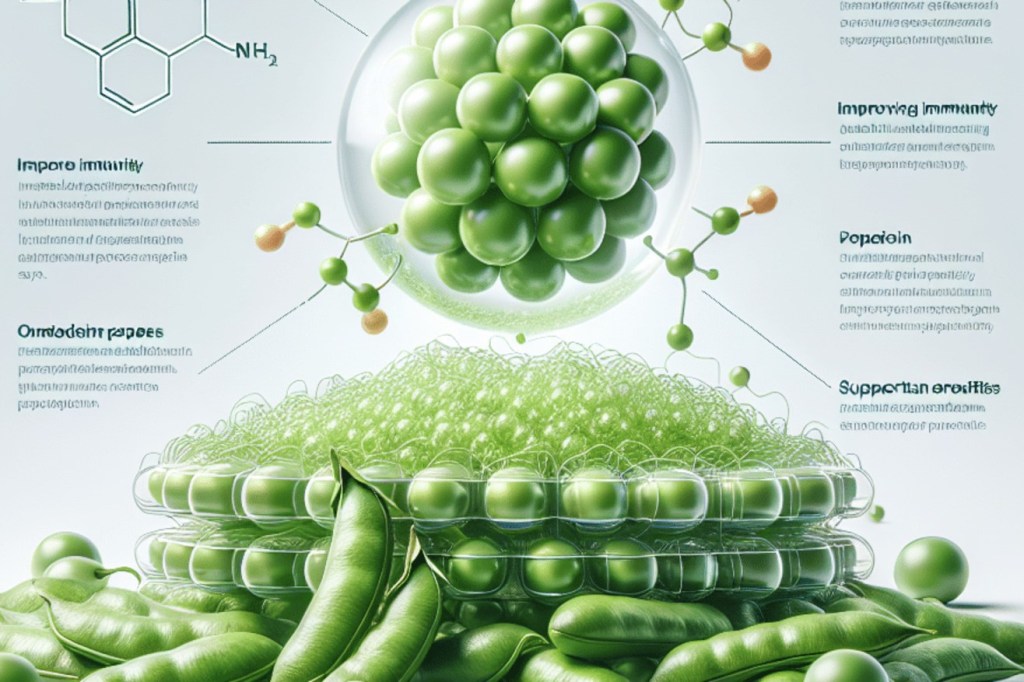

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) is a naturally occurring fatty acid amide, which is produced within our bodies as part of a response to inflammation and pain. PEA has been studied for its analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties. The liposomal form of PEA is encapsulated within liposomes, which are tiny vesicles that can encapsulate nutrients, enhancing their absorption and bioavailability.

What is Luteolin?

Luteolin is a flavonoid found in various plants, including celery, thyme, and green peppers. It’s known for its antioxidant properties and its ability to modulate the immune system, potentially reducing inflammation and providing neuroprotection.

Health Benefits of Liposomal PEA Plus Luteolin

When combined, liposomal PEA and luteolin may offer synergistic effects that can lead to various health benefits. Here are some of the most significant potential benefits:

Enhanced Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Both PEA and luteolin have anti-inflammatory properties. PEA acts on the endocannabinoid system, which plays a role in regulating inflammation and pain. Luteolin, on the other hand, can inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines. The combination of these two compounds may provide a more potent anti-inflammatory effect than either would alone.

Neuroprotective Properties

Neuroinflammation is a contributing factor in many neurodegenerative diseases. Luteolin has been shown to have neuroprotective effects, potentially slowing the progression of diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. PEA also exhibits neuroprotective properties, making the combination a promising candidate for supporting brain health.

Pain Relief

Chronic pain is a debilitating condition affecting millions worldwide. PEA has been studied for its analgesic effects and may be beneficial in treating various types of pain, including neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia. Luteolin’s anti-inflammatory action can further support pain relief.

Immune System Modulation

Luteolin has been found to modulate immune function, which can be beneficial in autoimmune conditions where the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues. PEA also has immune-modulating effects, potentially making the combination useful in managing autoimmune diseases.

Support for Allergies and Asthma

Allergic reactions and asthma involve inflammatory processes that luteolin can help mitigate. PEA may also contribute to reducing the severity of allergic reactions and asthma symptoms.

Scientific Research and Case Studies

Several studies and case reports support the health benefits of liposomal PEA and luteolin:

- A study published in the Journal of Pain Research found that PEA reduced pain and improved quality of life in patients with chronic pain conditions.

- Research in the European Journal of Pharmacology highlighted luteolin’s potential to protect neurons from damage and support cognitive function.

- A case study involving a patient with severe neuropathic pain showed significant improvement after treatment with PEA, suggesting its effectiveness in managing nerve pain.

These examples underscore the therapeutic potential of liposomal PEA plus luteolin, although more research is needed to fully understand their effects.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways on Liposomal PEA Plus Luteolin

In summary, the combination of liposomal PEA and luteolin offers a promising natural approach to managing inflammation, pain, and neurodegenerative conditions. Their synergistic effects can enhance anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective outcomes, potentially improving the quality of life for individuals with chronic health issues.

Discover ETchem’s Protein Products

If you’re interested in exploring the benefits of protein supplements alongside liposomal PEA and luteolin, ETchem’s range of high-quality protein products is worth considering. Their extensive selection caters to various health and wellness needs, ensuring you find the right supplement to complement your health regimen.

About ETChem:

ETChem, a reputable Chinese Collagen factory manufacturer and supplier, is renowned for producing, stocking, exporting, and delivering the highest quality collagens. They include marine collagen, fish collagen, bovine collagen, chicken collagen, type I collagen, type II collagen and type III collagen etc. Their offerings, characterized by a neutral taste, instant solubility attributes, cater to a diverse range of industries. They serve nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, cosmeceutical, veterinary, as well as food and beverage finished product distributors, traders, and manufacturers across Europe, USA, Canada, Australia, Thailand, Japan, Korea, Brazil, and Chile, among others.

ETChem specialization includes exporting and delivering tailor-made collagen powder and finished collagen nutritional supplements. Their extensive product range covers sectors like Food and Beverage, Sports Nutrition, Weight Management, Dietary Supplements, Health and Wellness Products, ensuring comprehensive solutions to meet all your protein needs.

As a trusted company by leading global food and beverage brands and Fortune 500 companies, ETChem reinforces China’s reputation in the global arena. For more information or to sample their products, please contact them and email karen(at)et-chem.com today.